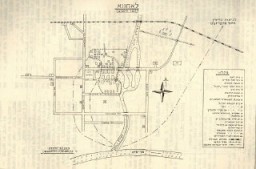

![<p>Map of showing Lachwa ghetto and surroundings (from Rishonim la-mered: Lachwa [First Ghetto to Revolt: Lachwa] (Tel Aviv: Entsyklopedyah shel Galuyot, 1957).</p>](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/d79f2c38-6260-4b15-ab3b-2cbda2c5b510.jpg)

Lachwa

As the Nazis conducted the Holocaust, they established over 1,150 ghettos throughout German-occupied eastern Europe. Among them was Lachwa.

A Project of the Miles Lerman Center

Pre-1939: Lachwa, Polesie province, Poland

1939-41: annexed to the Belorussian SSR

1941-44: Lachwa, Rayon center in the Pinsk district, Generalkommissariat Wolhynien-Podolien, Reichskommissariat Ukraine

1944-91: Lakhva, town in the Brest province, Belorussian SSR

Post-1991: Republic of Belarus

Łachwa lies on the Smierc River, 80 kilometers (50 miles) east of Pinsk. In the late 1930s, Łachwa had a total population of about 3,800. Approximately 2,300 Jews were living in Łachwa on the eve of World War II. In September 1939, approximately 350 Jews who had managed to escape from Poland found refuge in Łachwa.1

The first German troops reached Łachwa on July 7–8, 1941. A Judenrat was set up, headed by Dov Lopatin, who had been the chair of the Zionist organization in Łachwa before the war. Jews were compelled to wear an armband bearing the Star of David and were conscripted for forced labor.2

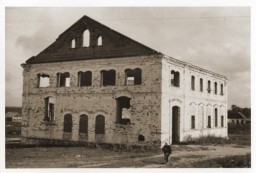

The ghetto in Łachwa was established on April 4, 1942.3 It consisted of 45 one-story houses. About 2,350 people were forced into the ghetto, which, as in Pinsk, amounted to roughly 1 square meter (10.8 square feet) per person.4 The ghetto was located on the river and was divided by a road that split it into a larger and a smaller part. Jews from the surrounding villages were also confined there. The ghetto was fenced in and guarded by the police force recruited from local Ukrainian and Belorussian residents. The meager food allowance for Jews in the ghetto (200 grams [7 ounces] of bread per day) drove Jews to seek food outside the ghetto. Leaving the ghetto without permission was punishable by death.

In August and September 1941, news of massacres in the surrounding towns spread in Łachwa. Beginning in January 1942, Jewish youth organized underground groups, with the first group of 5 youths coming together under the leadership of Isaac Roszczyn, the head of the Revisionist Betar youth group. Soon five more groups of 5 formed, bringing the total of underground members to 30. Other members of the resistance included Asher Hafets, Hersz Migdalowicz, Icie Slucki, the brothers Fajnberg, Lejzor Romanowski, and Lopatkin.5 The groups established contact with partisans in the area and with the Judenrat to secure funding and weapons, although antisemitism among local partisan groups limited the effectiveness of such contacts. While efforts to secure firearms were largely unsuccessful, members did manage to acquire axes, knives, and iron bars. Some firearms and grenades, which had been purchased, were hidden in the village of Liubka Lachowska. The Judenrat and the youth movement cooperated closely. The Judenrat also had offered money to purchase arms. Some members of the youth movement were also members of the Jewish Police who worked with both the Judenrat and the underground movement.

The liquidation of the Łachwa ghetto, which lay in the administrative area of the Łuniniec Security Police (Sipo) outpost (Aussendienststelle), began on September 2, 1942. SS- Sturmscharführer Wilhelm Rasp and his assistant Petsch led the Aktion; SS men Patik, Balbach, and Dohmen were among the hands-on executioners.6 All these men were part of the Sipo outpost in Pinsk. Support was given by the 2nd Company of Police Battalion 306 and by the 2nd Company of Police Battalion 69. Wehrmacht forces stationed in Łuniniec cordoned off the ghetto. The Judenrat was told to assemble all the Jews on the streets.

During the previous month, August 1942, the Jews in the Łachwa ghetto received news of the fate of the Mikaszewicze ghetto.7 At the time this information arrived, some local farmers had already excavated large pits in the vicinity of the town on the banks of the Smierc River. The pits were dug at night, and the victims knew full well that a mass grave had been prepared.8

Knowledge of the impending liquidation prompted different responses within the Jewish population. In general there was a feeling of helplessness and confusion within the community. Roszczyn and other members of his organization began to prepare for armed resistance. Although Roszczyn wanted to break out of the ghetto the night before, Lopatin asked him for time so that he could learn more about the Germans’ intentions. The Judenrat raised the issue of the continued existence of the ghetto with the Germans at two levels, first, with Ebner of the Gebietskommissariat, who informed the Judenrat that the same fate awaited the Łachwa ghetto if its inhabitants attempted to escape. He demanded and received from the Judenrat a list of the names of the ghetto inhabitants. Second, the chairman of the Judenrat, Lopatin, made inquiries with the Wehrmacht and was told that “the Jewish population has an important task ahead of them” and that the pits were purely for military purposes. Lopatin was summoned to Ebner just prior to the ghetto liquidation. Ebner waived all pretense and informed him that the ghetto was to be

liquidated and, in an attempt to obtain cooperation, proposed a deal whereby the doctor, the members of the Judenrat, and 30 artisans of Lopatin’s choosing would be spared. Lopatin declined the offer and refused to cooperate with the Germans, choosing instead to initiate the uprising that Roszczyn had demanded.

When the liquidation Aktion commenced, trucks were parked on the street dividing the ghetto. The smaller part of the ghetto was to be liquidated first. Immediately after the Sipo forces entered the ghetto, Lopatin set fire to the Judenrat headquarters, which was the signal to begin the uprising. Other buildings in the ghetto were then set alight, and the Jews tried to escape while the ghetto was burning. Thus the Łachwa Judenrat made a conscious decision to forego the illusion of salvation and to share the fate of the Jewish population. The Sipo forces retaliated with machine gun and rifle fire9 in an attempt to herd the Jews already assembled onto the trucks. Members of the underground attacked German forces, using axes, stones, and cleavers. Roszczyn killed a Gestapo officer with an ax and jumped into the river but was shot in the head.10 Lopatin, who had joined the fighters, was injured in the hand but managed to flee to the forest. The Jews had some hand grenades, which they used against the Germans.11 Chajm Chajfec was able to get the gun of a dead Gendarme and returned fire on the Germans. The resistance managed to kill six German and eight Belorussian policemen and injure some others. Approximately 1,000 Jews broke out of the ghetto, but hundreds were killed by German machinegun fire, and only 600 managed to reach the Pripjet River. Others died in the flames, which enveloped the ghetto, and those who did not escape in the flight from the ghetto were brought to the pits and shot. Kopel Kolpanitzky recalled his flight from the ghetto:

“The machine guns on the other side of the river opened fi re along the length of Rinkowa Street, wounding fleeing Jews and killing them. . . . I also ran quickly, as the people who ran in front of me were shot and killed, their bodies falling next to me and their blood sprayed on my body.”

Many of the 600 Jews who escaped into the forests tried to join the partisans, but at least 120 died or were captured before contact could be made.12 In the first few days after the escape, many were hunted down by the Germans and killed or handed over by local farmers.13 Some did succeed in joining the partisans. In the ghetto, the shooting was over by early afternoon. At least 300 were murdered at the pits. Another 1,500 Jews were killed during the uprising. At the end of the war, only 90 of the escapees from the Łachwa ghetto were still alive.

The Łachwa Judenrat acknowledged the reality of the imminent murder of the Jews and rebelled. It is interesting that such rebellions mostly took place in the smaller towns. This can perhaps be explained by the more tightly knit community and less-stringent control by the Germans, which meant that the Jews had more opportunity to resist than in the larger towns. In some other ghettos, better contacts with people outside enabled more of the young Jews to arm themselves.

Sources

Published sources include the Łachwa yizkor book: H.A. Mikhaeli, Y. Lichtshtein, Y. Moravtsik, and H. Shklar, eds., Rishonim la-mered: Lahva (Tel Aviv: Entsyklopedyah shel Galuyot, 1957). Also useful are the memoirs of Kopel Kolpanitzky, Nigzar le-hayim: sipuro shel nitsol geto Lahva (Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense, 1999), now also available in English as Sentenced to Life: The Story of a Survivor of the Lahwah Ghetto, trans. Harold Jacobson (London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2007). Another relevant publication used for this entry is Shmuel Spector, ed., Pinkas ha-kehilot. Encyclopaedia of Jewish Communities: Poland, vol. 5, Volhynia and Polesie (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1990), pp. 261–262.

Relevant documentation can be found in the following archives: AZIH (301/286, 2441, and 3087); BA-L (ZStL, II 204 AR- Z 393/59); Sta. Braunschweig; USHMM (RG-50.030*0260); VHF; and YVA (O-3/475, 481, 487-90, and 496).

Series: Resistance in the Smaller Ghettos of Eastern Europe

Critical Thinking Questions

- What obstacles and limitations did Jews face when considering resistance?

- What pressures and motivations may have influenced decisions and actions of the ghetto leaders? Are these factors unique to this history or universal?

- What pressures and motivations may have influenced the actions of the local population?

- How can societies, communities, and individuals reinforce and strengthen the willingness to stand up for others?

Further Reading

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945. Vol. 2, Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe, ed. Martin Dean. Bloomington: Indiana University Press in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2012.

Kolpanitzky, Nigzar le-hayim, p. 34.

Michaeli et al., Rishonim la-mered, pp. 44– 45.

Izak Lichtenberg, AYIH, 301/2441; also Leja Romanowska, 301/286. Mikhaeli notes in Rishonim la-mered that the Jews were forced into the ghetto on April 4, 1942 (14 Adar, 5702), the eve of the holiday of Passover; see p. 54.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR- Z 393/59, vol. 16, p. 4449, and vol. 19, p. 4711.

Leja Romanowska, AZIH, 301/286.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR- Z 393/59, statement of Otto Scholl, April 4, 1963, 2538.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR- Z 393/59, statement of Leon Slutzky, 9637. See also Mikhaeli et al., Rishonim la-mered, pp. 58– 59.

AZIH, 301/3087

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR- Z 393/59, statement of Bakalczuk, February 5, 1972, 6792.

Kolpanitzky, Nigzar le-hayim, p. 61.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR- Z 393/59, statement of Scholl, April 4, 1963, 2538.

Mojzesz Romanowski says that, in addition, 150 Jews were murdered by the partisans

Kolpanitzky managed to hide in the pig shed of a local farmer before joining a group in the forest; see his Nigzar le-hayim, pp. 65– 66. See also USHMM, RG- 50.030*0260.