Life After the Holocaust: Regina Gelb

With the end of World War II and collapse of the Nazi regime, survivors of the Holocaust faced the daunting task of rebuilding their lives. With little in the way of financial resources and few, if any, surviving family members, most eventually emigrated from Europe to start their lives again. Between 1945 and 1952, more than 80,000 Holocaust survivors immigrated to the United States. Listen to Regina Gelb's story.

Life After the Holocaust documenteds the experiences of six Holocaust survivors whose journeys brought them to the United States, and reveals the complexity of starting over.

Born in 1929, Regina was raised in Starachowice, an industrial city in central Poland. She was the daughter of Pola Tennenblum, an active member of the Zionist movement, and Isaac Laks, an engineer in the lumber industry. Regina was the youngest of three daughters.

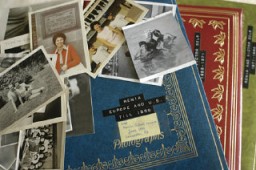

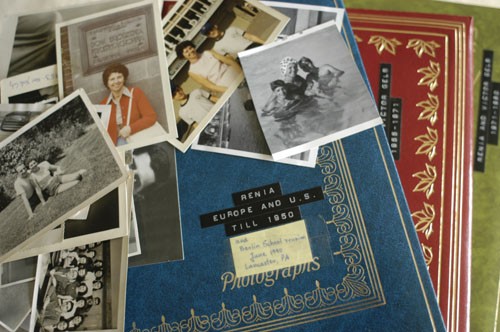

Regina Gelb: Family Photographs

Listen to Regina's Story

Transcript of Interview with Regina Gelb

Narrator: Music and photographs play an important role in Regina Gelb's life.

Regina: I just took out my album from our trip to Europe, specifically to Poland in 1980. And I'm looking at the pictures that were taken on our visit to Frederic Chopin's birth place in Zelazowa Wola, which is slightly north, I think. Near Warsaw, very near Warsaw. And it's amazing how vivid the memories of the lovely, lovely music that was played at... at the cottage. Later on, of course, after the Zelazowa Wola, we went...

Victor: What was the name of that park?

Regina: Lazienki Palace. That's an old palace.

Victor: Oh, the name is the same as the palace?!

Regina: Right.

Victor: I remember when we sat there, and we were enjoying a concert...

Regina: Yeah. Yes. And the piano was placed... on this..

Victor: beneath the statue (Regina: statue)... And the statue is of Chopin.

Regina: Right. Right.

Narrator: The purpose of Regina's first trip to Poland after the war, was to introduce Victor, her American-born husband, to the cultural heritage she loves so deeply. And to her painful past.

Regina: Ah, you asked me about the pictures of my family—from before the war. Of course, I have them. And it isn't because I took them out of Poland, no. They were sent to us from Israel. Because my mother was quite involved with training the pioneers for, for pioneering in Palestine. And subsequently these people settled in the old Palestine. And my parents used to send them pictures. Well, after the war, we were very, very lucky that some of these people whom we located gave us some of the pictures of, from my childhood, which I would otherwise never have.

Narrator: Born as Regina Laks in 1929, raised in Starachowice, an industrial city in central Poland, the daughter of Pola Tennenblum, an active member of the Zionist movement, and Isaac Laks, an engineer in the lumber industry, and the youngest of three girls.

Regina: The three sisters. The older sister Anna, Hania. The middle sister, Krysia, Chris. And myself Renia, Regina. Of course, we are a very close family. We always have been extremely close. And, because we survived the war together. And the fact that we were never separated during the war, which is almost incredible. It just absolutely was a miraculous thing that we were never separated. We were very close then, and we are very close now. And so are our kids.

Narrator: Hania was the academically gifted, the family "genius." Her test scores were so high that she became one of only a handful of Jewish students allowed into an elite Polish gymnasium in Radom. Before the war, Hania tutored fellow students in French and Latin. During the war, when Jewish children couldn't go to school anymore and the girls were kept inside for safety, Hania became a dedicated teacher for her sisters and a few friends. Krysia, the middle sister, was strikingly beautiful yet industrious and down-to-earth. It was her practical intelligence that helped save them later, when intuition and fast decision-making counted most. And Regina—thin, outgoing, curious. Nickname: "the information agency." Together, they survived three difficult years; first, in a forced-labor camp in their hometown; then in Auschwitz-Birkenau; briefly in the concentration camp Ravensbrueck in Germany; and finally in the small labor camp Retzov, a subcamp of Ravensbrueck. When they were liberated by the Russian army in April 1945, the sisters were 21, 19, and 16 years of age. They decided to return home. Slowly making their way by train, still in their Auschwitz clothing. On the train, near the Polish border, they were approached by a Jewish soldier in Russian uniform.

Regina: So he says, "You're one of those camp people?" So he says, "You're one of those camp people?" So we said, "Yes." "Where you going?" "We're going back to Poland." "Where in Poland?" We said, "Starachowice." "What kind of town is it?" Whether it was a big city, which of course it wasn't, because the population was 30,000 and that's no big city. So when he found out, he says, "No, you should not be going back to the small town, because they will not welcome you. They will think you're coming to claim your property or whichever it is, and a lot of people returning from camps are being killed now. So, you are better off going to one of three places. Warsaw, Cracow, or Lodz." He said, "Warsaw is all bombed out. Lodz has a very good Jewish agency set up. Best thing for you is to go to Lodz." And we decided, "Fine, so we'll go to Lodz. But where do we go?" And he says, "Well, I have a sister there," and he gave us the address. He says, "You go to her. Ring her doorbell and tell her that I send you. And there's a Jewish agency and you can register and, and from there on, you'll be all right." Which is exactly how it was and this is my, May, 1945, now. We came, and she had a lot of people—lot of people sleeping on the floor, sleeping on the stairway, all over the place. And the next day we went to register.

Narrator: The sisters checked every day for registered survivors returning from camps.

Regina: Now things were coming out in the open, about what really, truly happened. And it was incomprehensible. And to look for individuals, that was totally out of the question. But to look for people who were part of a group was easier, because genocide was predicated on mass murder, you see? So, if you were in the Ostrowjets group, you went to Treblinka, you see. If you were in another group, you went to Majdanek or Belzec.

Here is another picture, which I have... which shows my mother's side of the family, which was quite extensive. Because there were nine children. And when they grew up, of course, they all had children. So, the family was very large. In this picture I have my mother's oldest sister, Fela Kronenberg with her husband. My mother's sister Anja. Regina and Roosia. My mother's brother, Moishe. And the Kronenberg's two sons, whose name was Bernard and Henrik. And, of course, except for my uncle Moishe who emigrated to America, this, everybody in this picture was annihilated in the Holocaust. Plus—and this is only one daughter. Now, just multiply it by nine and you will get the idea of how many people in that family perished in the Holocaust.

Narrator: The sisters learned that their father had been murdered in Auschwitz, and that the transport with their mother on it had gone to the killing center Treblinka. But they also found out that their father's brother survived and was in Lodz. And since uncle Alexander had hidden assets, he was able to provide them all with a comfortable place to live.

Regina: We had a very good life in Lodz, in the sense that it was sort of like catching your breath. And we lived... Yes, I picked up as if I really belonged there. I really truly fit right in. I really fit right in.

Narrator: While her sisters went to work, Regina kept house and got herself admitted to high school.

Regina: And ahm, was a very interesting period of my life, because you see, I actually didn't finish elementary school, you see? But, because I was taught, right through the ghetto time, which was seven days a week, 10 hours a day, I knew French and I knew Latin and I knew grammar and I knew history and I read Tolstoy and—and I did all these things, which I would never have done, except the books were in the house and that's what we studied from. And my sister Hania, being the best teacher I ever had, which—it's a fact... I had this fantastic education.

Narrator: In early 1946 the family situation changed. The older sister, Hania, became engaged, and moved with her fiance to Warsaw to study diplomacy. The middle sister, Chris, also got engaged—to Miles Lerman. Uncle Alexander left for Sweden, where he had found his wife.

Regina: But Miles was now my guardian, you see? He married Krysia and I said, "Well, now you have a wife and you don't need a fifth wheel into the, to the wagon," you know? He said, "No, no, no. That's not how the way it's gonna work." He said, "No, that's the way we're going to work it, that until you get married, you'll stay with us." (Sighs) I was trying very hard not to be a burden, you know, in any way. But they were both very busy. He was working, she was working. Somebody had to run the house.

Narrator: Miles Lerman also lost most of his family, and he and Krysia decided to build a new life in America, where Miles still had an aunt. Regina, of course, would come with them. They made their way to a displaced persons camp in the American zone of Berlin, Germany, and registered for visas. Like most DP camps, camp Dueppel in Berlin-Schlachtensee was comprised of former German military barracks.

Regina: I have the pictures of the barracks. The barracks were not much to brag about. They were, I think, some old leftover army barracks or whatever. But when you're young, and you come back to living a life of a young girl, who cares if you live in a barrack or if you live in a palace! Because, as you could see from the album, ah... we were celebrating different holidays. For example, Lag Baomer as you could see, we're all dressed in school uniforms, which is a white blouse and a navy blue skirt. We went to somewhere out—it was an outing, like a picnic type. And here you have another picture of another picnic, specifically with my class. And some of these people are still around, and we're very good friends. This is a picture in the class room...

Narrator: There were children of all ages and nationalities. Camp survivors as well as refugees and Polish Jews returning from Russian exile. Many of them were still undernourished, and they received special meals that to Regina's delight included chocolate treats. The educational fare in the camp included theater trips along with Hebrew and English classes, biology and physics. For entertainment, there were outings and dances, where the bands played American pop songs of the 1930s.

Regina: And, of course, to this day every time somebody plays very old records and they play one of those, I never associate it with America. Because I really learned it in Berlin! (sings) "Kiss me once and kiss me twice and kiss me once again... It's been a long, long time... " I'm sorry, I can't sing, because I just had a cold. So I have a scratchy voice...

Narrator: Regina's DP camp experience differed sharply from that of many older survivors.

Regina: I wasn't shy and I wasn't reserved and I wasn't suspicious and I wasn't cynical. I haven't lived yet! I wanted to live, you know? Anybody was wonderful. Everybody was wonderful! Everybody I met was great! And they were going out of their way to... make us feel that we're children still, you see? That really did it. That really did it, because I was sort of pretending I was grown up when I was in Poland and I was accommodating myself and I was adjusting. But here I was just a child and it was perfectly fine and I got chocolate for it. So, you see, that really was the so-called smoothing over. And ahm... when we came to America, now then my child—not my childhood, but my young life really started.

[Steam boat signal]

Narrator: The SS Marine Perch arrived in New York Harbor on February 11, 1947—and Chris, Miles, and Regina were welcomed by Miles Lerman's aunt, who had sponsored them. After a few days in her home, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Commitee helped them find an apartment. The Joint also helped get Regina into a school outside of her regular district. Thomas Jefferson High School in Brooklyn's East New York.

Regina: And that was a, a blue collar Jewish neighborhood when I came in. And the school had very high academic level, because all these kids were what you call "eager beavers," you know. To get out of the, of the working class, you know. Alfred Kazin and all the writers and all kinds of important people came out. They went through this—living in that area and they broke out to greater things. Now, when I came to Jefferson, that was more or less the tempo of it, you know, you carried on.

Narrator: Apart from its high academic standards at the time, the school also had a newly established program for refugee children. Once a day, they would meet for an orientation class that covered basic English skills, provided evaluations of the students' academic skills in other subjects, as well as teacher advice and support. Equally important, "basic English" class familiarized the students with American customs and democracy.

Regina: So when I came here, and I told you, I found out all these things, that you are free to read the paper and you are free to express yourself and you can get up and disagree with your teacher in the classroom and all these things that you could do that were absolutely—that they had no repercussions—that you weren't going to be shot or killed or sent in the prison, or whatever. That was—it's like an explosion of the mind, to me.

[Sounds of Regina rummaging through her collection of buttons.]

Regina: If you allow me, I'll just look through this bunch of buttons, I have this whole bag here, you know. I don't even really know what is here, except that I dumped them all in one place so that they wouldn't be scattered. Now, let's see what I have. I have my senior button from Thomas Jefferson High School, 1949. Orange and blue, the colors of the school with two faces, boy and girl looking at each other. Really charming. This probably sounds awfully childish and all that, but I think this is the most precious thing. And I keep it and I'm not going to part with it! So, back it goes into the box with the buttons...

Narrator: Regina excelled academically. Became friends with teachers and students. Took on part-time jobs. She didn't talk much about the war.

Regina: So, all this really, to just sum it up, didn't...this life in Jefferson did not fit with sitting there comparing notes, "Did you go to Auschwitz?" "No, I didn't go to Auschwitz, I went to Ravensbrueck." That was past, that was water under the bridge, you know? Most of these kids went to college and graduated from college. So that you see, we were more or less on that same level of trying to get on with life in an—this new way, excelling educationally, find a place in this new world. And who wants to talk about this old stuff?

Narrator: Privately, the 18-year old mourned her parents.

Regina: I always missed them, you know, I always missed them. I grieved for the fact that there was no cemetery that I could go to. But mother went to Treblinka and father perished in Auschwitz, so where is the place? There is no place.

Narrator: There is no exact date of death either. Regina joined a group of other survivors from Starachowice who had determined October 27th—the day when their hometown was cleared of Jews—as the offical date for a commemorative service, a Yahrzeit.

Regina: Prayers were said. And then the morning prayers were said. And then there was coffee and cake and so on, a little socializing. So we did that once a year. And so that was the official mourning, but of course, I missed my parents a whole lot. But you know, I was thinking about it. If I were still in Poland, I probably would have missed them much more because they were, they fit into the setting. Here, I was sort of on my own, you know? I had Chris and Miles, of course. But after they moved away, I was really on my own and I knew that I absolutely cannot depend on having my mother help me out or my father help me out, you see?

Narrator: When Chris and Miles moved to New Jersey, Regina remained in Brooklyn and went to Brooklyn College. Then the Cold War Era began, and Indiana University needed a native Polish speaker to teach Air Force officers conversational Polish, in preparation for their jobs as attaches in Eastern Europe. Regina became an instructor in Bloomington, Indiana, and finished her BA in social work there. She appreciated life in the American heartland.

Regina: It was most rewarding as a final—it's a trite word, Americanization—but I was taken in to what this life was. In other words, now—not that I was done with Europe, you know, I can't be done with Europe, is like I can't be done with my right hand, you know—but I finally got into the spirit of the country and of...oh, I got involved, and I already had my ideas of politics and all this. It really, absolutely coalesced. It really got together. It, it formed into a, a unit.

Narrator: Before she left for Indiana, Regina met Victor Gelb, a young Jewish American. It was 1950, and Victor had been drafted into the Korean War. However, he was stationed in the US, and came to visit her in Bloomington when on leave.

Regina: Since we're rummaging through the albums, I just came across this old album where I have some of Victor's old pictures from home. Here he is in his uniform. He went to a private military school up in Ossining, New York. Doesn't he look spiffy here? Wow! All these buttons up and down. Isn't that cute? And this, I think, is his picture from Junior High School. Very sweet boy. He always was a sweet guy. First of all, he always had manners. And he's very considerate, and very... He's quiet by nature, but very profound and very devoted. And, of course, he made only the best father on earth and the best husband. So, I'm very lucky. That's absolute fact.

Narrator: Regina and Victor got married in 1953 and settled in New York City.

Regina: Originally I really wanted to do social work. I really truly did. For many reasons. One of them being the fact that I did go through the Holocaust and had I not been helped as a child I really wouldn't have survived. And I really felt I owed this goodness to other people and I ought to reciprocate. However, by the time I came out of college with an idea of going to graduate school for social work, the system changed, and I did not like the way the system was oriented toward... taking away the responsibility of the people to... to shift for themselves. Rather than helping them being on their own feet, this was a system now that was going to provide and provide and provide.

Narrator: Regina found other shortcomings in America. On one side, the anti-communist excesses of the McCarthy era. On the other, the anti-authoritarian chaos of the 1960s counter-cultural movements. Her ideal was a democratic society, ruled by law, in which she could raise her children to be open-minded, yet disciplined. When her two boys Harry and Paul went to elementary school and on to high school, Regina served as vice president in the parents' associations. Helping to set up library programs and fighting for high academic standards.

Regina: The kids were very much oriented to—not so much to succeed as to broaden their horizon. We did a lot of very interesting things. Kids used to go to summer camp, to the Boy Scouts for a month. And then we used to go traveling together, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Canada very often. All the way to Indiana to re-visit my school.

Narrator: Harry is a lawyer in New York City, Paul a landscape designer in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Both are married. Both have two children. Regina became an accredited member of the American Translators Association. She worked as an interpreter, did commercial translations, and translated Polish books and Polish materials for books.

[Music]

Narrator: Every major holiday still brings all three families together. Chris and Miles and their children from New Jersey; Hania and her children from Canada; Regina and her children.

Regina: I was so lucky to come here and to be a young girl in America, you know? I was just so lucky. And a lot of people who came, who weren't that much older, maybe 10 years older, they already had to go to work and they already had to struggle. They could never go back to school, you see? Or maybe they came with a child and it was—I came a young girl, like a—like a young horse, you know, ready to get out of the stable and run. I was just like that, you know? I was like an eager beaver. I was willing and ready and everything was a lovely, nicest experience even if it wasn't so nice. I thought it was great! Everything I did, everything—every summer camp, every baby-sitting, every this and that and the other thing. Everything was wonderful, because it was a new experience, you see? And it really took me away from—not that it took me away... it was something I didn't yet experience, you know. I came here, I hadn't lived yet. So everything that I lived was great! And in true fashion, it really was. I mean it was not an exaggeration, because all the things that happened to me, everything was sort of by chance, people—you know, I got a job to support myself by working in the ORT. I didn't look for it; they looked for it. I got a job to teach in Indiana. I didn't look for that. You know? You see what I mean? Every time I do something, I was asked to do it or something and it turned out a fantastic experience. So, that's fine.

Credits

Narrator: This program is part of "After the Holocaust," a series of audio profiles of Holocaust survivors in America. It was conceived and written by Regine Beyer and Arwen Donahue.

Studio production by Regine Beyer with Helen Thorington, engineer, at the New Radio and Performing Arts studio in Staten Island, New York.

The narrator was Jane Altman.

Special thanks go to the German Radio Archives, DRA, in Potsdam-Babelsberg; to Belgian producer Ronny Pringels, and to German producer Helmut Kopetzky for the use of sounds from their archives.

"After the Holocaust" is a production of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The interviews in this program were conducted for the Oral History Department of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, with financial support by the Jeff and Toby Herr Grant.

The Museum gratefully acknowledges Jeff and Toby Herr for making these interviews and this audio series possible.

Series: Life after the Holocaust: Audio Interviews with Holocaust Survivors

Critical Thinking Questions

- What challenges faced survivors of the Holocaust?

- How did various countries respond to the plight of survivors?