Mlynów: "Life under the German Occupation," According to Yehudit Rudolf

Read firsthand testimony about the occupation of Mlynów, the establishment of the ghetto, resistance activities, and the destruction of the ghetto.

A Project of the Miles Lerman Center

Yitshak Siegleman (ed.), Sefer Mlinov-Muravits (Haifa: Va`ad yots´e Mlinov-Muravits be-Yi´sra´el, 1970)

The Collective Testimony of: Yehudit (Mendlkern) Rudolf, Fanya (Mendlkern) Bernshteyn, David Bernshteyn (Hebrew)

“Life under the German Occupation,” according to Yehudit Rudolf, pp. 287–292

On Sunday, June 22, 1941, with the outbreak of the war between Russia and Germany, our town—that had a Soviet airfield—was bombed. My mother was injured in her leg. Several people were hurt and a few houses were destroyed during the bombardment.

On June 24, 1941, in the afternoon, the Germans entered the town. Before their arrival, there was a brief aerial battle. The Soviets had left the town defenseless on Monday. At 5:00 PM, on Tuesday afternoon, the first German soldiers entered our houses. My mother, who was injured, was lying on the floor out of fear of the bombardment; my brother Moshe (of blessed memory) was lying down pretending to be sick. There were five or six soldiers who came inside. They were looking for pork; we offered them some sour milk. But, when they heard that we were Jews, they shattered the pitcher and left.

A day or two after the conquest, written notices were distributed in German and Ukrainian that Jewish men and women of ages 14 and older must present themselves in the market for labor, equipped with tools and cleaning equipment. Whoever did not show up would be shot. Immediately, a Ukrainian police force was organized. Their badge was a blue and yellow armband on the left sleeve. In general, [Jewish] women were sent to do cleaning work and the men to dig and work in the fields in the estate of Count Hudkiwicz, who had disappeared in 1939.

A few days after the conquest, a group of Jewish youths (male and female) were arrested on grounds of having been Communist activists: Chaya Kipergloz, Rivka Bar, Freydl Rivits, and Yentl Mendlkern (my father's sister).

Some of the men (about 200), who were sent to work, were sent to the estate of Count Liudochowski, in the village of Smordwa. Jews were also brought there from the neighboring villages of Boremel and Demidowka. The director of the estate was a Volksdeutshe name Grüner, a cruel sadist, who would wake the men several times in the course of a night and order them to run. He would have them run down stairs. While they ran down the stairs, he would whip them with an iron bar so that they would fall down the stairs.

Only the Jewish blacksmith Hirsh-Ber (I do not remember his family name) benefited from a special relationship. He got enough bread and could even share with others. He also succeeded in getting medicine. He maintained his position until the liquidation; afterwards he was killed in the forest. If someone got sick, he would take him on as his assistant and thus save him-since it was forbidden to be sick.

In a month or six weeks after their arrival, the Germans sought out activists from the Polish [political] parties. Ten to fifteen Poles were arrested; coincidentally, they also arrested a young Jewish man named Yehuda ben Mordechai Liberman. The Germans misled the families of the prisoners [into believing they were alive] and even accepted packages for them. In fact, they had murdered all of them immediately after their arrest.

One night, early on, the Germans went into the house of Shlomo Kremer, a Jewish shoemaker. He had a beautiful daughter, Rachel—who escaped via the window upon seeing them. As revenge, the soldiers killed both her parents. Their son Zalman, who was in the village of Smordwa, burst out crying when he heard the news of his parents' murder. A German soldier, who noticed, asked him why he was crying. Upon hearing the reason, he shot him dead on the spot.

During the initial period, prior to the construction of the ghetto, there was no acute lack of food. Most of the families had stores of food. In addition, they also had items they could use to barter with the peasants. Somehow, everyone managed, even though barter was forbidden. Despite the ban, Jews would go to the peasants' houses and the peasants would come to the Jewish houses to barter.

Immediately after the conquest, the Jews were ordered to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David on their sleeves. A few months later, in the fall of 1941, they were ordered to replace the white armband with a yellow patch on the chest and back. This rule applied to everyone of ages 12 and above.

In the fall of 1941, the Judenrat and the Jewish police were set up. The former shopkeeper Hashas was appointed as the first chairman. The other members were: Mordekhai Litvak, Chaim Yitskhak Kupergloz (the former Kehila chairman); Katsman (the former Kehila secretary) was appointed secretary; also Mordekhai Liberman, David the Butcher (whose surname I forget), and Moshe ben Yaakov Holtsker. The police force included: Zelig Zider, Shlomo Shakhman, Perets Tesler, and Tsvi Gring. There were two or three others whose names I forget.

The district [Kreisgebiete] commissariat was located in the city of Dubno. In the fall of 1941 (I don't remember the exact date), an order was publicized for the entire district to provide 3,000 Jews as construction workers in the city of Równo to build barracks for the army. The Judenrat in Dubno did not want to send men with families and decided to gather men from all the towns in the district. [The Jews] in the towns did not know the purpose of the project. In each operation, Ukrainian policemen would surround the town and give an order to the Judenrat to hand over a specific number [of workers]. The Judenrat would draw up lists. They took about fifty men from Mlynów. Ukrainian and Jewish police went from house to house looking for the men on the list. Some of the men fled to surrounding fields and villages. In place of those who had fled, they took whoever was there. The arrest of the men was accompanied by crying and weeping.

The men were in fact brought to work in Równo. During the next two months, we received news from them. After they finished the work, they were all murdered; none of them came back. In order to mislead the youths who worked there, several of them were deliberately sent home for a “vacation.” They, of course, confirmed the news that the men were in fact working and even getting vacations.

About a week after [the men were taken away], a unit of the Hungarian army arrived whose task was to confiscate grain, beans, and flour from the houses of the Jews. Of course, they were unscrupulous and took whatever they found. Thus, Jews lost their food supplies. Nevertheless, until the final moments most of the town's Jews did not suffer from true famine, since they were still able to obtain food through barter.

That fall, there were two additional events: the confiscation of gold and the confiscation of furniture. In the “gold operation,” the Jews were ordered to bring their gold and silver jewelry and utensils, dollars, and other jewelry. All of them got receipts for everything they turned in. After the gold operation came the fur operation—in the end of the summer of 1942 [this was probably at the end of 1941 or in early 1942 to equip the German Army during the winter, ed.]. Afterwards, the Germans came with hundreds of Ukrainian police and wagons and confiscated everything they could get their hands on-bicycles, sewing machines, and regular furniture. The operation ended suddenly: a whistle was sounded, after which some furniture that they had no time to load on the wagons was left behind.

Among the first victims, during the summer of 1941, was the town's rabbi—Rabbi Yehuda Gordin. He was called from his house by Germans and imprisoned for several days before he was taken to be killed. It was said in the town that the Rabbi could speak German well and therefore they interrogated him and harassed him for several days. Afterwards, they killed him outside of town.

Before Passover [April 2–9] 1942, the Judenrat obtained permission to bake matzot. The baking was done in two places and done for everyone in the community. The Germans did not investigate the source of the grain.

In the last days of fall 1941, the Judenrat announced that whoever had a work certificate would not be taken to the ghetto (we had already been told that there would be a ghetto) and [would be] considered a productive element. Fictitious marriages began to take place between women and men who were assigned various jobs, especially craftsmen, including those who work on farms, as mentioned above. Afterwards, a trade in work-certificates began. There were also different categories of certificate. The “best” kind were the “iron certificates,” which were issued to dentists, gold- and silversmiths, doctors, and other craftsmen employed by the Germans to meet their personal needs.

An example of the certificate trade: Perl Mendlker, the wife of Yitskhak Mendlkern (now living in Israel), traveled to Dubno to obtain one of these certificates for her brother-in-law. As it happened, an Aktion was occurring in Dubno at the time and she was taken and murdered. In that Aktion, 5,000 Jews were murdered in a field where they had been assembled. One of them-Leyb Vinukor (now living in Israel)-pulled down a plank from the fence, fell upon one of the German guards, stunned him, and managed to escape and hide. He was with us in the forests later.

In Mlynów itself it was difficult to obtain these certificates; it was in Dubno that the trade really sprung up. Before the establishment of the ghetto, it was still forbidden for Jews to travel from one city to another. Although travel to Dubno was illegal, Jews would travel with Ukrainian peasants going on trips-of course with the peasants' approval. Every one of these trips involved mortal danger. On one of these illegal journeys Yaakov Nudler-who was going to get arms for the fighting organization and of whom we will speak later-was arrested and murdered.

The Ghetto

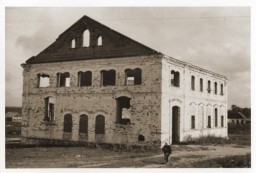

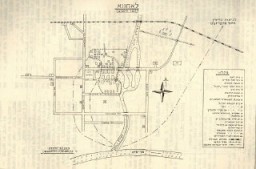

In April 1942, a ghetto was established. Two streets served as its borders: Szkolno and Duwinska. Permission was given for Jews from other streets to take their personal their belongings with them. Those who were expelled from their homes moved into the residential houses on these streets. Most of the time, they privately found place for themselves to stay; in a few instances the Judenrat made the arrangements. Due to the overcrowding, the sanitary conditions worsened severely. In our apartment—two rooms—there lived our uncle, grandmother's family, and her two grandchildren (the children of Yente, who had been murdered during the first days of the occupation). In general, about seven or eight people had to live in one room. The ghetto was surrounded by barbed wire and had two gates, guarded by Ukrainian police. The Jewish police usually accompanied those leaving the ghetto to work. Except for those who left to do ordered work, nobody was allowed to leave the ghetto.

The general attitude was to do anything to leave the ghetto. Those who did agricultural labor were envied by those in the ghetto. My sister Fanye worked in the German office for roadwork and she had a work certificate. The German soldiers assigned to this office were Austrians and were reasonably good to her. She returned to the ghetto every evening. During her work, she made contact with a Polish family named Wejczurk, and from them she was able to obtain food. Thus she began to discuss with them [the possibility of] hiding when the ghetto was liquidated. The head of the family was a keeper of the roads.

Immediately after the ghetto was set up, a general feeling set in that this was the prologue to the ghetto's liquidation. A few youths, among them my brother Moshe Mendlkern, the brothers Shlomo, Yaakov, and Yitskhak Nakunitshnik, and the policemen Zelig Vider, Tsvi Gring, Perets Tesler, and Shlom Shakman; Rachel Liberman, Rivka, Liberman, Lyuba Tshizhik, Hannah Wayner, Zelig Pikhnyuk, and others tried to organize resistance. At the head of the group was Avraham Ben-Tsion Holtsker. Shlomo Nakunitshnik, who before the war had lived by himself outside of town, had connections with people in the forests that had arms. One of the partisans, a Pole, promised to provide arms for the Jewish youth [in Mlynów]. The youth gathered money for buying the arms and also prepared gasoline to burn down the ghetto when [the Jews] were being gathered for the purpose of liquidating the ghetto, in order to create confusion so that it would be possible to escape. The group obtained two rifles, which were entrusted to Avraham Holtsker. It was decided that if the flight to the forests was successful, those who fled would go to the forests of Polesie and join a partisan group, since the first rumors of their establishment had already reached us. The members of the group gathered almost every evening, but were unable to take tangible action. The arms were hidden in the “tent,” which stood over the grave of Rav Aharon of Karlin, of the Stolin dynasty.

Those who were on the farm in the village of Krolinka prepared two bunkers in the forest, in which there were tools and blankets. These bunkers were necessary [to house] those who fled from the ghetto at the time of the liquidation. Those who did this were: my brother Moshe Mendlkern, Shmuel Gruber, and Yitskhak Mendlkern. It should be noted, that there were youths from all of the youth organizations in this underground group: Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa'ir, HeHaluts ha-Tsa'ir, and Betar-and they cooperated completely. It is notable that the pupils of the youth movements joined forces, apparently a product of the education that they had received.

During the final months of summer, in August or September 1942, rumors came of liquidations of ghettos in other towns and cities. It was clear that Mlynów's turn was coming, and that its Jews were condemned to death.

In September it was found out that the peasants of the area had been ordered to prepare a large pit in the valley between the towns of Mlynów and Muravica, known as the kruzhuk, about a kilometer from town. The first victims thrown into this pit were the brothers Fishl and Shlomo, the sons of Nahum Taytlman (now living in Israel). They had left the ghetto without permission. Apparently, they had wanted to hide in some village. They were caught in the evening, sent to the pit, murdered, and thrown into the pit.

Before the liquidation of the ghetto, all the Jews who worked outside the ghetto on various farms were ordered to return to the ghetto. There were those who returned willingly, in order to be with their families, and those who had to be brought by force by the Ukrainian police in an organized fashion.

The Massacre

On October 8, 1942, the ghetto was surrounded by Ukrainian police under German command. Loudspeakers announced that it was forbidden to leave. From time to time, Jews brought back to the ghetto from the places they worked arrived separately and in groups. They all understood that this was the end. Men, women, and children went into the streets. Panic and hysteria broke out. People prayed wept, screamed, and reunited with their families.

When night fell, loudspeakers announced that everyone had to go into their houses and not light any fires. Anyone who left his house would be shot on the spot. From time to time lone gunshots were heard—or the rattle of the police motorcycles in the ghetto.

Series: Resistance in the Smaller Ghettos of Eastern Europe

Critical Thinking Questions

- Consider the importance of firsthand testimonies. What can we learn from them?

- Across Europe, the Nazis found countless willing helpers who collaborated or were complicit in their crimes. What motives and pressures led so many individuals to persecute, to murder, or to abandon their fellow human beings?

- How can societies, communities, and individuals reinforce and strengthen the willingness to stand up for others?