The Role of the German Police

Persecution of Jews and other groups did not result solely from measures originating with Hitler and other Nazi zealots. Nazi leaders required the active help or cooperation of professionals working in diverse fields who in many instances were not convinced Nazis. Germany’s policemen played a key role in the consolidation of Nazi power and persecution and mass murder of Jews and other groups.

-

1

Before Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, each German state had its own police forces.

-

2

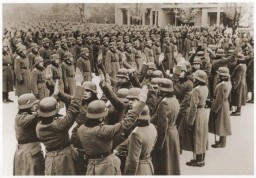

In 1936, police forces across Germany became centralized under SS leader Heinrich Himmler. They became instruments of state-sponsored racial, political, social, and criminal persecution.

-

3

During World War II, German police forces perpetrated numerous crimes at home and abroad as part of the German occupation forces.

Before the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, there was no national police force. During the Weimar Republic (1918-1933), each German state had its own police forces. Usually this included uniformed policemen, political policemen, and detectives. Though policemen had similar responsibilities and purposes in the various states and regions of Weimar Germany, they also carried out tasks specific to their local communities and job descriptions. Being a uniformed policeman in Berlin was very different from being a uniformed policeman in the countryside.

Policemen's attitudes toward Nazism were shaped by events of the 1920s and early 1930s. In this period, the Nazis hoped to undermine the government’s stability through political violence. They targeted those they considered enemies, especially Communists and Jews. The often rowdy and violent Nazis were deliberately disruptive to public order. They brawled with the equally disorderly Communists and other political opponents, attacked Jewish passersby, vandalized businesses they considered Jewish, and sometimes battled the police. Germany’s police forces struggled to respond to this political disorder. They had to balance their own political inclinations, the freedoms of the Weimar Republic (including freedom of speech and assembly), and their role as guarantors of public order.

Some Nazi promises appealed to Germany’s policemen. Many Germans, including some policemen, did not like parliamentary democracy or the Weimar Republic. Some wanted a return to authoritarianism, which would bring the extension of police power, a strong centralized state, and the end of factional party politics. The Nazi Party promised all of this and more. Even as they deliberately initiated violence and chaos, the Nazis promised to bring order and discipline to the German streets.

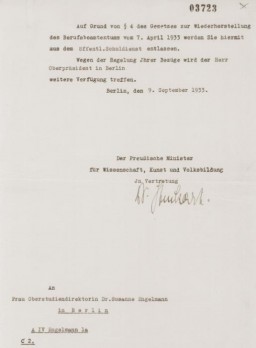

After Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933, the Nazis sought to gain control of Germany’s different police forces. They eventually succeeded. In 1936, Hitler appointed SS leader Heinrich Himmler as Chief of the German Police (Chef der deutschen Polizei), who centralized the police under his control. Himmler worked to merge the SS and the police together into one institution, made up of different branches. New laws and decrees allowed the police to arrest, imprison, and torture people defined as enemies with impunity. In 1933, the police used these new powers primarily to target political opponents, especially Social Democrats and Communists. Later, the police adopted a new Nazified approach to crime and political opposition. They could preventively arrest and imprison potential enemies and criminals in concentration camps without judicial oversight.

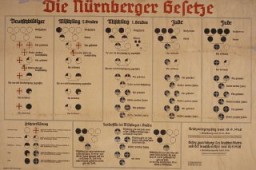

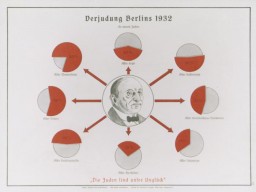

Beyond maintaining order, arresting political opponents, and solving crimes, the police became instruments of racial persecution. The Gestapo investigated cases of “race defilement” and violations of anti-Jewish laws. In the 1930s, uniformed Order Policemen (Ordnungspolizei) often ignored Nazi violence and vandalism, especially when it was a government- or party-sponsored action. This was the case, for example, with Kristallnacht.

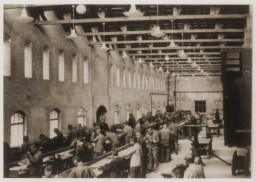

During World War II, the role of the German police radicalized. German police units were deployed alongside the military, and were typically tasked with maintaining security behind the front lines in occupied territories. German police forces perpetrated numerous crimes at home and abroad. Individual policemen guarded Jews and Roma during deportations, arrested and tortured political and racial “enemies,” and vigorously punished any anti-Nazi resistance. Police units, including Einsatzgruppen and Order Police Battalions, guarded ghettos, facilitated deportations, pursued Germany’s enemies, crushed resistance movements, and carried out mass shootings of Jews and others.

Series: German police

Series: The Role of German Professionals and Civil Leaders

Switch Series

Critical Thinking Questions

- Consider the role of the police. How might their oaths and traditional responsibilities be tested in times of social upheaval?

- How were the police involved in preparing and carrying out the laws, orders, and policies which implemented the whole process? What lessons can be considered for contemporary professionals?

- How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity?