Postwar Trials

After World War II, international, domestic, and military courts conducted trials of tens of thousands of accused war criminals. Efforts to bring to justice to the perpetrators of Nazi-era crimes continue well into the 21st century. Unfortunately, most perpetrators have never been tried or punished. Nevertheless, the postwar trials did set important legal precedents. Today, international and domestic tribunals seek to uphold the principle that those who commit wartime atrocities should be brought to justice.

-

1

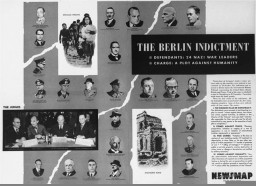

Between 1945 and 1949, Britain, France, the Soviet Union and especially the United States tried Nazi diplomatic, economic, political, and military leaders before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) established in Nuremberg, Germany. The Nuremberg trials are the best known of the postwar trials.

-

2

In the postwar period, tens of thousands of German perpetrators and their non-German collaborators were tried by courts in Germany or in the nations that Germany occupied during World War II or that collaborated with the Germans in the persecution of civilian populations. Efforts to bring the perpetrators of Nazi crimes to justice have persisted well into the 21st century.

-

3

The trials of perpetrators of Nazi crimes set lasting legal precedents and helped to establish the now widely accepted principle that crimes like genocide and crimes against humanity should not go unpunished.

Background

Before World War II, trials had never played a major role in efforts to restore peace after international conflict. After World War I, for example, the victorious Allies forced Germany to give up territory and pay large sums in reparations as punishment for waging an aggressive war. During World War II, however, as Nazi Germany and its Axis allies committed atrocities on a massive scale, trying those responsible for such crimes in a court of law became one of the war aims of the Allied powers.

In October 1943, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin signed the Moscow Declaration of German Atrocities. The declaration stated that at the time of an armistice, Germans deemed responsible for atrocities would be sent back to those countries in which the crimes had been committed. There, they would be judged and punished according to the laws of the nation concerned. “Major” war criminals, whose crimes could be assigned no particular geographic location, would be punished by joint decision of the Allied governments.

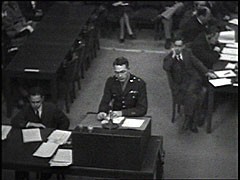

The International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg

In August 1945, Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the United States signed the London Agreement and Charter (also called the Nuremberg Charter). The Charter established an International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg, Germany, to try major German war criminals. It assigned the IMT jurisdiction over crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, which include such crimes as "murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation...or persecutions on political, racial, or religious grounds."

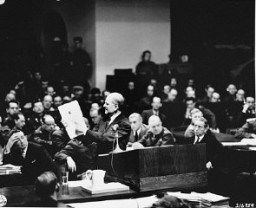

The most famous of the war crimes trials held after the war is the trial of 22 leading German officials before the IMT in Nuremberg. This trial began on November 20, 1945. The IMT reached its verdict on October 1, 1946, convicting 19 of the defendants and acquitting 3. Of those convicted, 12 were sentenced to death, among them Reich Marshall Hermann Göring, Hans Frank, Alfred Rosenberg, and Julius Streicher. The IMT sentenced 3 defendants to life imprisonment and 4 to prison terms ranging from 10 to 20 years.

In addition to the Nuremberg IMT, the Allied powers established the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo in 1946, which tried leading Japanese officials.

Subsequent Nuremberg Trials

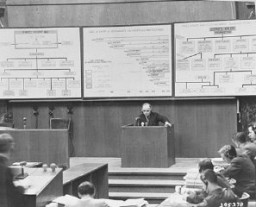

Under the aegis of the Nuremberg IMT, US military tribunals conducted 12 further trials. These trials are often referred to collectively as the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings.

Under the aegis of the Nuremberg IMT, US military tribunals conducted 12 further trials. These trials are often referred to collectively as the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings.

Between December 1946 and April 1949, US prosecutors tried 177 persons and won convictions of 97 defendants. Among the groups who stood trial were: leading physicians; Einsatzgruppen members; members of the German justice administration and German Foreign Office; members of the German High Command; and leading German industrialists.

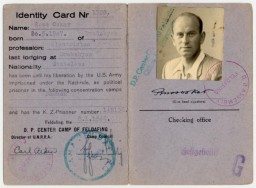

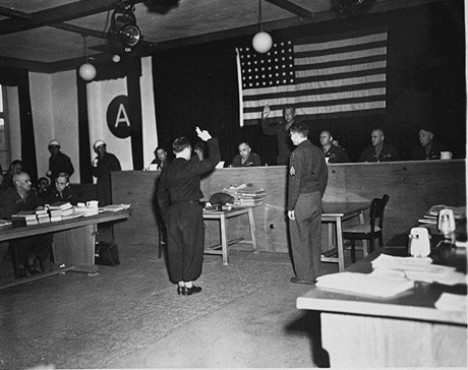

Other Trials in the Allied Occupation Zones

In the immediate postwar years, each of the four Allied powers occupying Germany and Austria—France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States— tried a variety of perpetrators for wartime offenses committed within their zone of occupation. The overwhelming majority of these post-1945 war crimes trials involved lower-level Nazi officials and functionaries. Much of our early knowledge of the German concentration camp system comes from the evidence and eyewitness testimonies at some of these trials.

Allied occupation officials saw the reconstruction of the German court system as an important step in the denazification of Germany. Allied Control Council Law No. 10 of December 1945 authorized German courts to try crimes against humanity committed during the war years by German citizens against other German nationals or against stateless persons in Germany. As a result, such crimes as the Nazi murder of persons with disabilities (referred to by the Nazis as “euthanasia”)—where both victims and perpetrators had been predominantly German nationals—were tried under newly reconstructed German tribunals.

Postwar Trials in Germany

In 1949, Germany was formally divided into two separate countries. The Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) was established in the zones occupied by Britain, France, and the United States and was allied to those countries. The German Democratic Republic (East Germany) was established in the Soviet occupation zone and was allied with the Soviet Union. Both countries continued to hold trials against Nazi-era defendants in the following decades.

Since 1949, over 900 proceedings trying defendants of National Socialist era crimes have been conducted by the Federal Republic of Germany (meaning, West Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990 and united Germany afterwards). These proceedings have been criticized because most defendants were acquitted or received light sentences. In addition, thousands of Nazi officials and perpetrators never faced trial, and many returned to the professions they had practiced under the Third Reich. For example, former Nazi officials comprised the majority of judges in West Germany for several decades after the war.

Other Postwar Trials

Many nations that Germany occupied during World War II or that collaborated with the Germans in the persecution of civilian populations, including Jews, also tried both German perpetrators and their own citizens who had perpetrated crimes during the war. Czechoslovakia, France, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union, among others, tried thousands of defendants. For example, the Soviet Union held its first trial, the Krasnodar Trial, against local collaborators in 1943, long before World War II had ended.

In Poland, the Polish Supreme National Tribunal tried 49 Nazi officials who had perpetrated crimes during the Nazi occupation of Poland. Among them was Rudolf Höss, the longest serving Auschwitz commandant. He was sentenced to death and hanged in the execution block at Auschwitz in April 1947. The Supreme National Tribunal also tried and sentenced to death other Auschwitz personnel, including former commandant Arthur Liebehenschel, as well as Amon Göth, who commanded the Plaszow concentration camp.

By 1950, international concerns about the Cold War eclipsed interest in achieving justice for the crimes of World War II. Trials outside of Germany largely ceased, and most of the convicted perpetrators who were not executed were set free during the 1950s.

The Eichmann Trial

Outside of Poland, crimes against Jews were not the focus of most postwar trials, and there was little international awareness or understanding of the Holocaust in the immediate postwar period. This changed in 1961 with the trial of Adolf Eichmann, chief administrator of the deportation of European Jews, before an Israeli court. The Eichmann trial also brought attention to the presence of accused Nazi perpetrators in a number of countries outside Europe, because Eichmann had settled in Argentina after the war.

In 1979, the United States Department of Justice established the Office of Special Investigations to pursue the perpetrators of Nazi crimes who were living in the United States. A decade later, Australia, Britain, and Canada also sought to prosecute Nazi perpetrators living within their borders. The hunt for German and Axis war criminals has continued into the 21st century.

Legacies

The postwar prosecutions of Nazi crimes set important legal precedents.

In 1946, the United Nations unanimously recognized the crime of aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity as offenses under international law. The UN subsequently recognized additions to international criminal law designed to protect civilians from atrocities. For example, in 1948, the UN adopted the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Since the end of the Cold War, a number of special tribunals have tried international crimes committed in specific countries, such as the genocide committed in Rwanda in 1994. In 2002, a new, permanent International Criminal Court began to operate. Domestic courts in some countries also prosecute the perpetrators of international crimes. Although such prosecutions remain rare, today there is widespread agreement that states have a duty to protect civilians from atrocities and to punish those who commit them.

Series: International Military Tribunal

Series: After the Holocaust

Switch Series

Critical Thinking Questions

- How did national histories, agendas, and priorities affect the effort to try war criminals after the war?

- The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg is the best known of postwar trials. Investigate trials conducted by individual countries in the late 1940s.

- Besides military leaders and government officials, which professions were specifically investigated in trials?

- Beyond the verdicts, what impact might war crimes trials have?