Communism

Communism is an economic and political philosophy grounded in the belief that societies are shaped by their economic systems. According to communism, capitalism creates social problems by dividing wealth unfairly between two classes of people. Therefore, the economic system must be reformed to distribute wealth equally. Communist ideas spread rapidly in Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries, offering an alternative to both capitalism and far-right fascism and setting the stage for a political conflict with global repercussions.

Key Facts

-

1

The Russian Revolution led to the creation of the Soviet Union as a communist state in 1917.

-

2

The Communist Party in Germany (KPD) peaked with 16.9% of the vote in the November 1932 elections before Hitler came to power in 1933 and subsequently banned all political parties other than the NSDAP.

-

3

The first Nazi concentration camp opened at Dachau in March 1933 to imprison political opponents of the Nazi regime. The first 100 prisoners were German Communists.

Definition and Origins

Communism is a specific form of the broader philosophy of socialism. Communism is further left on the political spectrum than socialism. However, both communism and socialism share similar understandings of the relationships between economic structures and social conditions, and between the individual and the state. Although there are many versions of socialist philosophy, socialism generally retains private property ownership and calls for gradual political change. By contrast, communist theory holds that change will occur via a proletariat revolution that will abolish private property.

Communism originated with the German philosopher/intellectual Karl Marx (1818-1883). In 1848, he published The Communist Manifesto with Friedrich Engels (1820-1895). The Communist Manifesto argues that the story of history is the story of class struggle. Communism posits that industrial society is divided into two classes of people: the proletariat (workers) and the bourgeoisie (capitalists). The interests of the two classes are in conflict. The bourgeoisie, who own the factories and businesses, profit from the labor of the proletariat—at the proletariat’s expense. Moreover, the problems of industrial society, such as the poverty Engels described in The Condition of the English Working Class (1844), are inherent in capitalism. The powerful elites could not be expected to voluntarily give up control. Therefore, communists predicted that the collective struggle of the working class would lead to the proletariat revolution and the elimination of capitalism in favor of a classless society based on the principle of “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

Communism in Practice

Soviet Union

Communist ideas spread rapidly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Communist political parties formed in every state across Europe, but they achieved the most success in Russia under Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924). Lenin was the leader of a faction of Russian communists known as the Bolsheviks. The term Bolshevism refers to Soviet-style communism. Bolshevism has significant departures from traditional Marxist communist theory.

Russia had been ruled by the Romanov dynasty since the 17th century. By the late 19th century, Russia faced a series of challenges that culminated in World War I. For Russia, World War I was a disaster, causing widespread hunger and popular unrest. In 1917, the country collapsed into revolution. The Romanov dynasty was deposed. Following several months of disorder and civil war, Lenin seized control and established the Soviet Union.

After Lenin’s death, Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) assumed power. Stalin consolidated his power by removing or killing real or perceived political dissenters. He implemented a series of Five Year Plans for the economic growth of the Soviet Union. These plans distorted Marxist communist theory into violent totalitarianism. Under Stalin’s dictatorship, the Soviet government exercised near-complete control over citizens’ private and public lives through terror and repression.

Germany

Socialist parties in Germany grew out of the trade union movement and began achieving electoral success in the late 19th century. By 1912, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany, SPD) was the largest party in the Reichstag (German parliament). In 1918, the left wing of the socialist movement split off to form the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (Communist Party of Germany, KPD) under Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) and Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919). In the first election after the war, the Social Democrats won almost 40 percent of the vote. SPD leader Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925) became the first president of the Weimar Republic from 1919 to 1925. The Social Democrats remained the largest party in the Reichstag until the July 1932 elections.

The Communist Party was never as popular as the Social Democrats. It reached its electoral peak in November 1932 with 16.9% of the vote. Within six months of this election, however, Hitler had seized power. He banned political parties other than the Nazis and began imprisoning German communists at Dachau.

Anti-Communism

Socialist and communist philosophies had never been popular with Europe’s conservative elites. They considered these beliefs to be dangerous ideologies that threatened their traditional political and economic control. The Russian Revolution and emergence of the Soviet Union increased fears of violent revolution and a radical reordering of society. These fears played out both within Germany and across Europe. Within Germany, Hitler was able to become chancellor in 1933 in part due to President Paul von Hindenburg’s (1847-1934) fears of communism—the Nazi party was reliably anti-communist.

Across Europe, a similar logic governed international reaction to Hitler’s new Third Reich. By the 1930s, Stalin had initiated forced collectivization, or the replacement of private farms with state-run, collective farms. He had also established industrial production quotas. His efforts eliminated the free market. This also gave the rest of the world a glimpse of the type of communist revolution the Comintern, a Soviet-controlled, global communist organization, was encouraging internationally. If communism were to spread from the Soviet Union into Germany, it would reach into the heart of Europe. The fear of communism prompted several European leaders—including British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain—to focus at first on Nazism’s anti-communist credentials rather than its territorial ambitions or antisemitism.

Judeo-Bolshevism: Communism in the Nazi Imagination

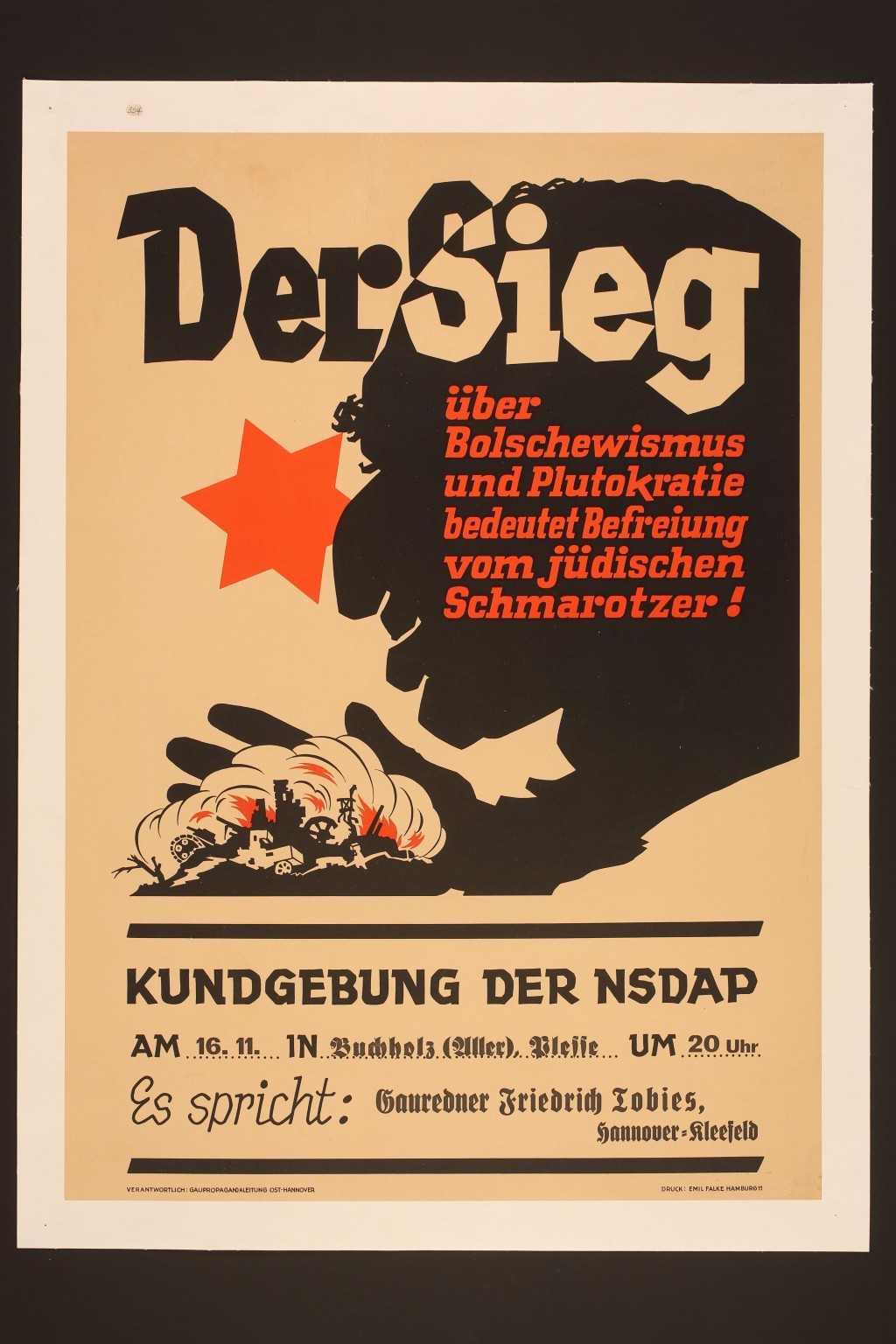

Communism was antithetical to Nazism because communism prioritized class above nation and race. However, in the Nazi imagination, communism was recast as Judeo-Bolshevism. Judeo-Bolshevism claims that communism was a Jewish plot designed at German expense. Judeo-Bolshevism’s threat was emphasized by Germany’s proximity to the Soviet Union and competing Nazi-Soviet territorial ambitions in Eastern Europe. The existence of a communist state so close to Germany was not merely a political threat, but also an existential racial and ideological threat. For Nazis, both Jews and communists were made worse by their supposed identification with one another.

As soon as the Nazis rose to power, they began targeting communists, both inside and outside Germany. In 1933, the first concentration camp opened at Dachau to hold political prisoners. The first prisoners were all communists. Later in 1933 the Nazis banned all political parties. They intensified the targeting of Communists, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. As early as 1933—before the Nazi regime had made any significant moves against Jews or the disabled—German Communists were detained in mass arrests and tortured. Once the war began, the Commissar Order demonstrated the depth of Nazi fear and hatred of communism. Issued in June 1941, the Commissar Order directed German soldiers to “shoot on principle” all Soviet commissars (Soviet Communist Party officials) and POWs, in violation of international law.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme, 1875, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/.

-

Footnote reference2.

Dieter Nohlen and Philip Stöver. Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 2010.

-

Footnote reference3.

Directives for the Treatment of Political Commissars (“Commissar Order”) (June 6, 1941). German History in Documents and Images. http://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1548.