Jews of the Maghreb on the Eve of World War II

North African Jews did not constitute a single community before or during World War II but, rather, were a diverse population of roughly 500,000. There were variations between the present-day countries of the Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya); by class, sub-ethnic histories, region; and by rural or urban lifestyle.

Demographics

For centuries before World War II, indigenous Jews lived in distinct yet porous ethnic quarters or communal spaces alongside Muslims in both the urban and rural regions of North Africa. These areas came to be designated as the mellah in Morocco and parts of western Algeria, and as the hara through the rest of Algeria, Tunisia, and Tripolitania in northwestern Libya. In predominantly Berber and Arab communities in rural and mountainous regions of North Africa, Jews and Muslims tended to live side by side.

Small communities of Italian, French, and other European Jews also settled in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. There were many indigenous Jews who acquired foreign nationality, either by being naturalized en masse by a colonial power (in the case of Algerian Jewry) or by seeking the protection of a foreign state. Cross-regional migration further nuanced the cultural and legal landscape.

On the eve of World War II, North Africa’s Jewish landscape was further diversified by the arrival of large numbers of Jewish refugees from Europe.

Language and culture

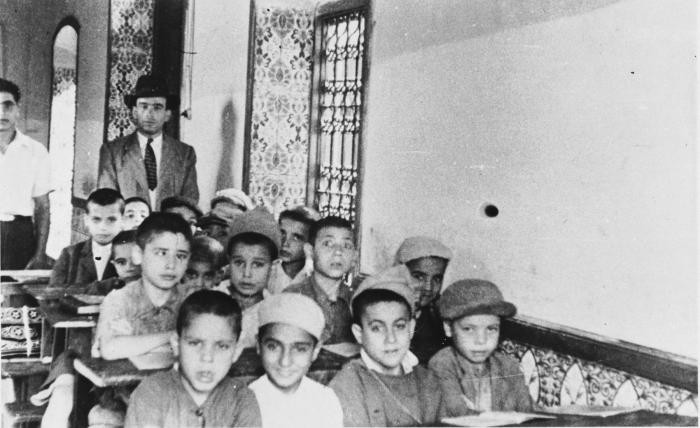

North Africa’s Jews, like the region’s Muslims, historically spoke a number of languages, including Arabic and Berber. In most of the Maghreb, Arabic was the primary language spoken by Jews in most regions; in instances where dialects of Berber were dominant, bilingualism was common among Jewish families, although Arabic was usually spoken at home. There is also evidence of a few mono-Berberophone Jewish communities.

In Northern Morocco, a unique form of Judeo-Spanish known as haketia existed alongside Arabic but was increasingly replaced by more standard Spanish as of the turn of the twentieth century. At that time, other European languages, especially French, assumed new prominence among North African Jewries as Jewish families gravitated toward the languages as tools of education and social ascension. In addition, the introduction and popularization of the printing press led to a flourishing in modern Hebrew letters among North African Jews.

Even as North African Jews in general underwent acculturation into European cultural milieux, a large percentage of the Jewish community maintained Arabic and Berber as a daily language. Judeo-Arabic and occasionally Judeo-Berber were also used in religious and commercial writings. In Morocco and much of Tunisia and Libya, for example, Arabic remained the dominant tongue.

Algerian Jewry was witness to more dramatic cultural and linguistic transformation, as so many took on French under the decades of French colonial rule (1830-1962): but here, too, much varied by region. The Jews of Constantine, in eastern Algeria, were far more likely to speak Arabic than were the Jews of Algiers and Oran—and this pattern fluctuated with class. Constantine was also one of many sites where Jews, alongside Muslims, served as performers and innovators of Arabic-language music, both the Arabo-Andalusian classical traditions, which traced their origins to Islamic Spain, and new, modern forms.

While Jews preserved Arab culture and Arabic language, other cultural changes marked Jews’ transition away from traditional cultural norms and towards new, hybrid ones. The movement to European quarters of cities and the consumption of ready-to-wear fashion marked North African Jews (like their Muslim neighbors) as participants in the profound cultural shifts reshaping the twentieth-century Maghreb.

The legal realm

Jews in North Africa lived under different legal regimes in the decades before the World War II, and these differences—rooted in colonial history—would be perpetuated under the Vichy, Nazi, and Italian fascist regimes that occupied the region during the war.

Algeria had been integrated into France since 1848, but few Algerian Berber or Arab Muslims had been granted citizenship by the state: most of Algeria’s Muslims were therefore French nationals, but “indigenous subjects of France” rather than French citizens. Through the colonial era, Algerian Jews were placed in another legal category, as the 1870 Crémieux Decree had granted citizenship to most, excepting the small population of Jews in the military districts of the Sahara. In Morocco and Tunisia, protectorates of France, Jews were considered subjects of the sultan and bey (respectively), except for a minority who obtained French or Italian citizenship; and these residents, too, were subject to beylical authority and that of makhzan (the central government).

These differential legal statuses applied to Jews would be repurposed under the regimes that ruled North Africa during World War II. In October 1940, for example, the Vichy regime abrogated the Crémieux Decree, returning Jews in Algeria to a state of legal indigeneity. That status, combined with the implementation of anti-Jewish race laws, meant that Algerian Jews held an inferior status relative to Muslims for the first time in seventy years.

Finally, a small but powerful percentage of Jewish women, men, and children in North Africa held the passports of European nations, in some cases because they worked for these states’ consuls. This legal status afforded Jews opportunities under colonialism: however, under Vichy, Nazi, and Fascist Italian rule it could also prove a legal liability, opening one up to possible deportation from North Africa or France to the death camps in occupied eastern Europe.

Anti-Jewish sentiment and Jewish responses

Nineteenth-century French Algeria was a particularly rich breeding ground for antisemitism, and from here the movement spread to other parts of North Africa. In the immediate aftermath of the Crémieux Decree of 1870, French-language antisemitic literature proliferated and violence against Algerian Jews by Europeans surged. By the turn of the twentieth century, Max Régis (né Massimiliano Régis Milano) and Edouard Drumont were elected to local and national offices on explicitly antisemitic platforms. In fact, Algeria often served to nourish antisemitism in metropolitan France, rather than the other way around.

Generally speaking, episodes of anti-Jewish violence by Muslims were comparatively rare in early twentieth-century North Africa. For the most part, both violence and antisemitism tended to emanate from the European Catholic settler colonial population or flow from them to local Muslim communities, as with the Constantine Riots of 1934.

During the 1920s and 1930s, antisemitic political associations reemerged to protest what they perceived as the exploitation of Algeria by Algerian Jews. Newspapers such as La Croix de Feu, Le Front Paysan and the Unions Latines launched campaigns blaming Jews for the economic turbulence of the era. These sentiments led to outbreaks of violence between Christians and Jews (as well as between Muslims and Jews) in Algeria. In the city of Constantine alone, 59 such episodes could be counted between 1929 and 1934.

Jewish responses to this violence included the establishment of Le Comité d’Union Sémite Universelle, an organization based in Algiers and other Algerian cities, which aimed to counter anti-Semitic propaganda and advocate for a shared Muslim-Jewish administration of Palestine. Echoing the goals of Le Comité d’Union Sémite Universelle, Muhammed al-Kholti, a moderate Moroccan nationalist leader, wrote a 1933 column calling for an entente between Muslims and Jews.

In response to these dynamics and other changes reshaping North Africa and the world, Jews in the region found themselves drawn to competing political movements in the decades leading up to World War II. Jewish youth, as well as Jewish women and men, identified with the French civilizing mission, as well as with anti-colonial nationalism, Zionism, and communism. In some cases, they embraced multiple movements, despite the seeming ideological contradictions between them.

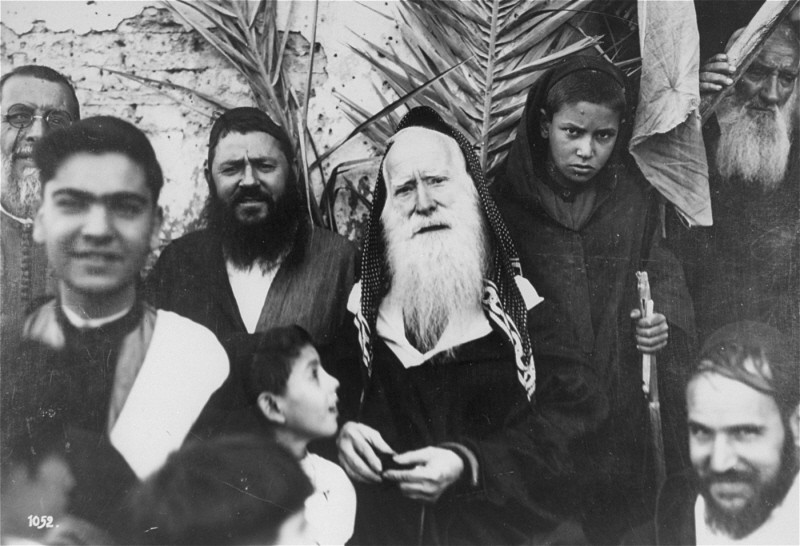

Religious and spiritual realms

In the religious realm, too, North African Jews occupied a wide spectrum of practices and identities, even if many Jewish families in the region continued to observe Jewish law and ritual in their daily practice. By contrast, Algeria was witness to a certain growth of secularism as Jews assimilated into French culture and sometimes married Christian spouses.

Religious knowledge was concentrated in certain family lines in North Africa (as elsewhere in the Jewish world), and passed from generation to generation. While the Kabbalah was integrated into the rabbinical works and religious thinking of scholars, it was also part of the popular practice of Jews.

Additionally, many North African Jews observed rituals unique to the region, and they shared some of these rituals with their Muslim neighbors. For example, throughout North Africa, Jews made—and continue to make—pilgrimage (ziyara) to tombs of holy men (tsadikim or qedoshim) on the anniversary of the holy man’s death. Known as the hillula, this Jewish celebration derives from the Kabbalistic belief that the soul of righteous saints unites with God upon their death.

All told, the Jews of North Africa were a highly diversified community on the eve of World War II: as diverse, one might say, as the Jews of Europe.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Learn about the diverse Jewish communities of North Africa before World War II.

- What was the relationship between German expansion and the fate of Jews in North Africa?

- Explore recent scholarship about the geographic extent of the Holocaust.