Mannschafts-Stammlager (Stalag) IX B

Millions of people suffered and died in camps, ghettos, and other sites during the Holocaust. The Nazis and their allies oversaw more than 44,000 camps, ghettos, and other sites of detention, persecution, forced labor, and murder. Among them was Mannschafts-Stammlager (Stalag) IX B.

History

The Wehrmacht established Mannschafts-Stammlager IX B on December 1, 1939, in Defense District (Wehrkreis) IX and deployed it to Wegscheide, near Bad Orb. The camp was liberated by American troops on March 30, 1945. The camp was subordinated to the Commander of Prisoners of War in Defense District IX (Kommandeur der Kriegsgefangenen im Wehrkreis IX). The camp commandant at the end of the war was Oberst Karl Sieber, and his deputy was Oberstleutnant Albert Wodarg.

Stalag IX B held Polish, French, Belgian, Czech, British, Serbian, and Soviet prisoners of war (POWs) (as of December 1941), and Italian military internees (as of fall 1943). In late December 1944, 985 American prisoners captured during the German offensive in the Ardennes were placed in the camp. By spring 1945 there were 4,700 American prisoners in the camp. The maximum camp population was 25,000.

The first prisoners to arrive at the camp were 14,000 Frenchmen. Most of them were immediately assigned to labor details (Arbeitskommandos), as were most prisoners of other nationalities. Many of the prisoners were employed in agricultural and forest labor (particularly Soviet prisoners), while others were employed at factories or by local government authorities (such as the City Construction Office, or Stadtbauamt).

Medical cases at Stalag IX B were treated at the camp hospital in Bad-Soden, which operated independently of the Stalag itself. This facility had a capacity of 300 beds and consisted of two separate buildings. The lower building was principally for prisoners from Stalag IX B. There they stayed in wards of up to 25 patients each. The upper building, by contrast, focused on eye care and the Bad-Soden hospital became the central hospital for optometry for POWs in Germany. The optometry building occupied a former rheumatism clinic, and so the facility was well equipped and suited for medical use, unlike many of the more hastily constructed camp hospitals.

Overall conditions within the 2 camp hospital units were generally superior to those elsewhere in the German prison camp system. The facilities were well-constructed and food quality and quantity was high, owing to a convent attached to the units, whose nuns provided all the meals. Patients were fed one of 3 meals based on their health. Prisoners had access to a library, and a camp theater was installed in one of the dining rooms.

The treatment of the French and Belgian prisoners by the German administrators and guards was decent early in the war, and the conditions in the camp were generally satisfactory and in compliance with the main provisions of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War (1929). In late 1944 and early 1945, however, conditions deteriorated significantly, because of the increasing disruption that Germany’s military situation engendered. The situation of Jewish-American prisoners, of whom there were approximately 130, was particularly difficult. They were separated from the other prisoners and housed in separate barracks before being sent to a subcamp of Buchenwald at Berga along with about 350 prisoners who had committed various violations of camp rules.

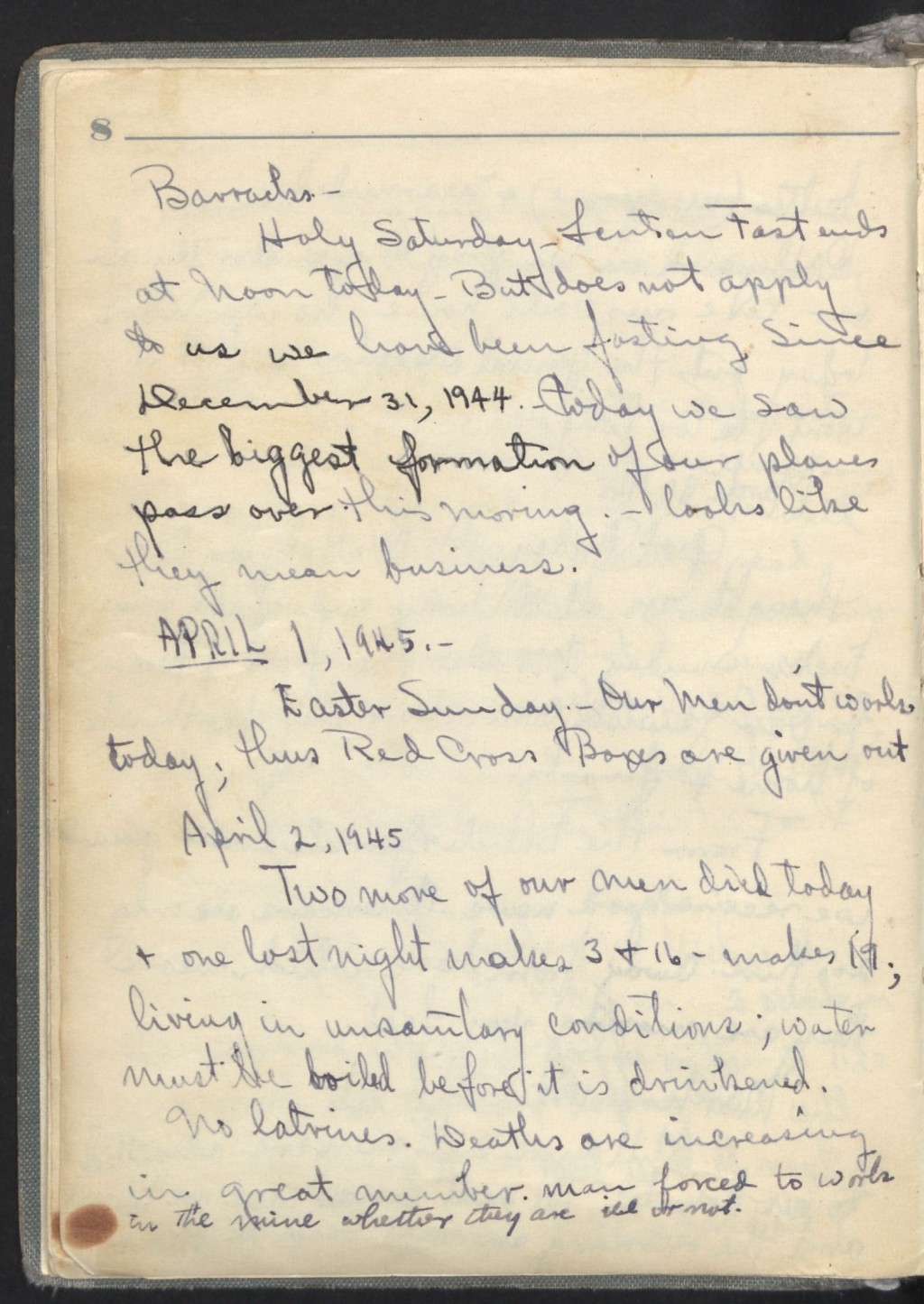

For British and American prisoners, Stalag IX B was one of the worst camps in Germany. Conditions were appalling from the start and continued to deteriorate as the war progressed. The first transport of American prisoners arrived in late December 1944. By January 24, the camp had 4,075 Americans, held in 16 barracks. The compound had formerly accommodated Soviet prisoners, and almost no changes to the facilities had been made prior to the arrival of prisoners from the Western front. According to the commandant, the camp personnel had received little to no notice that these prisoners would be arriving, so they had made no preparations.

The facilities would have been inadequate for even half the number of American prisoners they were expected to accomodate. Nearly 1,500 men slept on the bare floor, many without blankets, in mostly unheated rooms. Of the 16 barracks, 3 lacked beds, and several others had less than half the beds needed. The few rooms that were heated had small stoves and prisoners were given supplies of wood barely sufficient to heat the room for more than a few hours. As a result of the poor heating, ceilings and walls were frequently damp and at risk of collapsing. German authorities provided little more than cardboard for repairs. Prisoners had no cleaning supplies, primitive toilet facilities, and no way to wash their clothes. Though food rations were decent, the majority of prisoners had to use their helmets as bowls.

Conditions continued to deteriorate throughout the winter and into the spring. International observers described Stalags IX A, B, and C as “situation critical” following an inspection of the camps in March 1945. Hygiene in the camp became “nonexistent” and food rations declined. Poor sanitation and inadequate shelter had contributed to widespread cases of dysentery and pneumonia. The camp became infested with vermin. Overcrowding worsened with the arrival of 2,000 British prisoners. Observers warned of the “grave danger of epidemics” such as typhus breaking out in the camp. In Stalag IX B in particular the German authorities exacerbated the problems by harassing international observers and failing to make any efforts to provide needed supplies and repairs for the collapsing camp infrastructure.

The increase in the number of American prisoners towards the end of the war further burdened the already overcrowded camp. The scarcity of building materials made it nearly impossible for the camp leadership to address the problems within the camp. The water supply in the camp was heavily strained. The camp needed to provide water to an estimated 10,000 more prisoners than initially intended, overburdening the capacity of the existing water pumps. There were chronic shortages of medical supplies, clothing, and food.

The Jewish prisoners and disciplinary violators arrived at Berga on February 13, 1945. They were housed in barracks near the camp perimeter and were assigned to Arbeitskommando 625, which was responsible for digging tunnels for an underground ammunition factory; because this work was of a military nature, it constituted a violation of the Geneva Conventions. Their treatment was little better than that of other Buchenwald inmates. Former prisoner Alan Reyner stated that “[i]f we took one minute’s rest, we were beaten with a shovel or spiked with a pick. All the foremen carried rubber hoses which they didn’t mind using.”Prisoners frequently suffered from lung ailments due to the white dust churned up during their work. Medic William Shapiro recalled seeing bodies dangling from the gallows in Berga as he retrieved the prisoners’ meals from the camp kitchen.

On March 21, 1945, Red Cross parcels sent to Berga from Stalag IX C in Bad Sulza arrived, but the guard company commander, Erwin Metz, would not allow prisoners to receive them until they washed their uniforms. Reyner recalled of himself and his fellow prisoners that “[w]e had reached the stage of animals…. [E]ven sick men had their food stolen from them before they could even get it.”On April 3, 1945, the day after the main camp of Stalag IX B was liberated, the American prisoners at Berga were marched southward toward Bavaria. Their route took them through the towns of Hof and Fuchsmühl before coming to an end at Rötz, where they were liberated by the U.S. Army. 73 Americans died during the march, the highest number of Americans who perished in any such march in the European theater of the war.

The conditions for Soviet prisoners in Stalag IX B were similar to those in other camps for Soviet POWs, and the inhumane treatment they received resulted in a high death rate; for example, in 1942, 1,430 Soviet prisoners died in the camp. A cemetery containing the bodies of 1,433 dead Soviet prisoners was located in a forested area about a kilometer from the camp; these prisoners were buried in 12 mass graves, marked with an Orthodox cross.A Gestapo team regularly screened the Soviet prisoners in the camp to weed out “undesirables,” such as Jews and communists, who were then sent to a concentration camp (such as Buchenwald or Sachsenhausen), where they were executed on arrival.

Sources

Primary source material about Stalag IX B is located in the BA-MA (Bestand: RW 6: v.450-453; RH 53-9/17: Mannschaftsstammlager IX A-C); in the WASt Berlin (Stammtafel Stalag IX B); in NARA (RG 389; T 1021, 40-IX B, Vol. 22); in TNA (WO 224/30: Stalag IX B Bad Orb; FO 916/1150: Stalag VIIIA, VIIIB, VIIIC, IXB); in BArch B 162/15557-15558 (Aussonderung und Tötung sowjetischer Kriegsgefangener im Stalag IX in Bad Orb zwischen Herbst 1941 und Frühjahr 1943); in the IWM; and the USHMMA (Acc. 1996 A. 250).

Additional information about Stalag IX B can be found in the following publications: Ministère de la Guerre, État-Major de l’Armée, 5ème Bureau, “Stalag IX B,” Documentation sur les Camps de Prisonniers de Guerre (Paris, 1945), 243-247; Georg Tessin, Verbände und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen-SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945. Dritter Band: Die Landstreitkräfte 6-14 (Frankfurt/Main, 1966), 150; Gianfranco Mattiello and Wolfgang Vogt, Deutsche Kriegsgefangenen- und Internierten-Einrichtungen 1939-1945. Handbuch und Katalog: Lagergeschichte und Lagerzensurstempel, vol. 1 (Koblenz, 1986), 21; Mitchell G. Bard, Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler's Camps (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1994); Vasilis Vourkoutiotis, Prisoners of War and the German High Command: The British and American Experience (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003); “The Lost Soldiers of Stalag IX-B,” The New York Times (February 27, 2005); Flint Whitlock, Given Up For Dead: American GIs in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga (New York: Basic Books, 2006); Roger Cohen, Soldiers and Slaves: American POWs Trapped by the Nazis’ Final Gamble (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005); and Ernest W. Michel, Promises to Keep, foreword by Leon Uris (New York: Barricade Books, 1993).

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Liste der Kriegsgefangenenlager (Stalag und Oflag) in den Wehrkreisen I-XXI 1939 bis 1945, BA-MA, RH 49/20; BA-MA, RH 49/5; Tessin, Verbände und Truppen, 150; Mattiello and Vogt, Deutsche Kriegsgefangenen- und Internierten-Einrichtungen, 21.

-

Footnote reference2.

Personnel cards of Col. Karl Sieber, Commander of Stalag IX B, Jan. 2, 1945, and Lt. Col. Albert Wodarg, Deputy Commander of Stalag IX B, Nov. 16, 1943. Nov. 16, 1943-Jan. 2, 1945, NARA T 1021, 40-IX B, Vol. 1, Personalkarten.

-

Footnote reference3.

Mattiello and Vogt, Deutsche Kriegsgefangenen- und Internierten-Einrichtungen, 21.

-

Footnote reference4.

Investigation File 161, ITS Digital Archive 2.2.0.1/0046/0462.

-

Footnote reference5.

For details, see: “Life in Stalag IX-B. Story of an American Held in a German POW Camp,” by Pete House, 106th Infantry Division, 590th Field Artillery Battalion, Battery A; Bericht über den Gesundheitszustand der Kgf des Stalags IX B/Report of the Main Camp IX B physician, Dr. Jaitner, concerning the health of the prisoners of war and the general food conditions at Stalag IX B. Mar. 29, 1945, NARA T 1021, 40-IX B, Vol. 22.

-

Footnote reference6.

Bard. Forgotten Victims.

-

Footnote reference7.

Report by the International Red Cross (24 January 1945), NARA II, RG389, Box 2150.

-

Footnote reference8.

Report by the International Red Cross (24 January 1945), NARA II, RG389, Box 2150.

-

Footnote reference9.

Telegram from International Red Cross to US Delegation (17 April 1945), NARA II, RG389, Box 2150.

-

Footnote reference10.

Memorandum, US Department of State (7 April 1945), NARA II, RG389, Box 2150.

-

Footnote reference11.

Telegram from International Red Cross to US Delegation (17 April 1945), NARA II, RG389, Box 2150.

-

Footnote reference12.

Telegram from International Red Cross to US Delegation (17 April 1945), NARA II, RG389, Box 2150.

-

Footnote reference13.

Report by the International Red Cross (23 March 1945), NARA II, RG389, Box 2150.

-

Footnote reference14.

USHMMA, Acc. 1996 A. 250, Alan J. Reyner, Jr., typed memoir, Page 8.

-

Footnote reference15.

Shapiro, “An Awakening: Personal Recollection and Appraisal of My Prisoner-of-War Experience,” cited in Whitlock, Given Up For Dead.

-

Footnote reference16.

Diary of Anthony Acevedo, cited in Cohen, Soldiers and Slaves, 173.

-

Footnote reference17.

USHMMA, Acc. 1996 A. 250, Reyner memoir, Page 8.

-

Footnote reference18.

“Orte der Ausgrenzung - Frankfurter Schulen 1933–1945,” Lagergemeinschaft Auschwitz - Freundeskreis der Auschwitzer (Münzenberg) 27, vol. 1, Mitteilungsblatt (June 2007), 26.

-

Footnote reference19.

Erklarung zur Planskizze des Russenfriedhofs des früheren Lagers Wegscheide and der Hindenburstr. bei Bad Orb, ITS Digital Archive, 2.2.0.1/0042/0185.

-

Footnote reference20.

Aussonderung und Tötung sowjetischer Kriegsgefangener im Stalag IX in Bad Orb zwischen Herbst 1941 und Frühjahr 1943, BArch B 162/15557.

Critical Thinking Questions

To what degree was the local population aware of this camp, its purpose, and the conditions within? How would you begin to research this question?

How did the functions of the camp system expand once World War II started?

Did the outside world have any knowledge about these camps? If so, what, if any, actions were taken by other governments and their officials?

What choices do countries have to prevent, mediate, or end the mistreatment of imprisoned civilians in other nations?