Seeking Refuge in Cuba, 1939

In May 1939, several ships, including the passenger liner St. Louis, brought Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany (including recently annexed Austria, Bohemia, and Moravia) to Havana, Cuba. Three such ships carrying refugees seeking safety were the Orduña, the Flandre, and the Orinoco. These ships arrived in Havana harbor, but not all their passengers were allowed to disembark.

Orduña

On May 27, 1939, the day that also saw the arrival of the St. Louis, the British Pacific Steamship Navigation Company's Orduña landed at the harbor in Havana, carrying 120 Austrian, Czech, and German Jews. The Cuban authorities permitted 48 Orduña passengers, all of whom held landing permits, to enter Cuba, but refused to allow the remaining 72 passengers to disembark. The Orduña set off again on May 29, bound for South America, but with no assurance that the passengers would be allowed to land in any harbor. Two days later the passengers appealed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a radiogram for US assistance, noting that 67 of the 72 remaining refugees held affidavits or registration numbers for immigration into the United States and had intended to wait in Cuba for their entry visas to be issued.

For weeks the Orduña sought a safe harbor that would accept the refugees. After traveling through the Panama Canal, the ship made brief stops at ports in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. While in Ecuador, a Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) representative arranged refuge for four of the 72 Jews. At the same time, the Orduña's captain made contact with Rabbi Nathan Witkin, Jr., a representative of the US-based Jewish Welfare Board stationed in the U.S. controlled Canal Zone. With the support of the British Pacific Steamship Navigation Company and the JDC, Witkin arranged for the remaining 68 refugees to be transferred in Lima, Peru, to the British Orbita, which was en route to Europe via the Panama Canal.

Witkin then persuaded US authorities in the Canal Zone to permit the Orbita's refugee passengers to disembark in Balboa, a town near the Pacific end of the zone. Once in Balboa, seven Jewish refugees obtained Chilean entry visas and departed for Chile. The remaining 55 stayed in Balboa at Fort Amador, the location of the Canal Zone Quarantine Station, until the end of September 1940. With the assistance of the JDC and the New York-based Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, Rabbi Witkin arranged the transfer to the United States of the 55 refugees and 79 additional refugees, who had arrived at Fort Amador since May 1939, on the US transport ship American Legion.

Flandre

The success in finding refuge in the United States for the Orduña's passengers was not matched for other Jewish refugees arriving in Havana harbor in 1939. At the end of May 1939, the French Line's Flandre brought 104 German, Austrian, and Czech Jewish passengers to Havana. As in the cases of the St. Louis and the Orduña, Cuban officials would not permit the Flandre's passengers to disembark, and the ship set sail for Mexico. During the second week of June, the Flandre sought permission for its refugee passengers to disembark at several Mexican ports, but without success. After a short time, the Jews aboard the Flandre were forced to return to France, where they were subsequently admitted but interned by the French government.

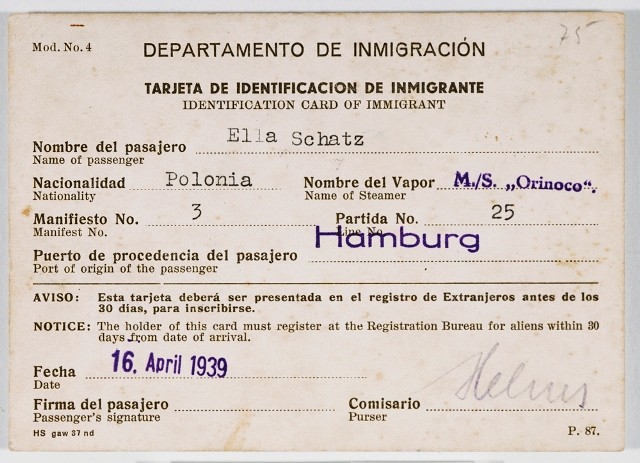

Orinoco

Similarly, on May 27 the Orinoco, the St. Louis' sister ship, left Hamburg with 200 passengers bound for Cuba. Informed by radio of the difficulties in Havana, the captain of the Orinoco diverted the ship to waters just off Cherbourg, France, where it remained for days. The Cuban treatment of the St. Louis refugees, and to a lesser extent of those aboard the Flandre and Orduña, had focused international scrutiny on Cuba's immigration procedures. Nevertheless, neither the British government nor the French government was prepared to accept the Orinoco refugees. The United States government then intervened, but halfheartedly. US authorities did not accept the refugees either, though US diplomats in London pressured the German ambassador to give assurances that the German authorities would not persecute the Orinoco refugees upon their return to the German Reich. With this dubious assurance, the 200 refugees returned to Germany in June 1939. Their fate remains unknown.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What pressures and motivations may have affected the decisions to deny landing permission to passenger liners with Jewish refugees?

- Why might the story of the story of the St. Louis be more famous than the voyage of the Orduna or the Flandre?