Third Reich

Both inside and outside Germany, the term “Third Reich” was often used to describe the Nazi regime in Germany from January 30, 1933, to May 8, 1945.

The Nazi rise to power marked the beginning of the Third Reich. It brought an end to the Weimar Republic, a parliamentary democracy established in defeated Germany after World War I. The last years of the Weimar Republic were plagued by political deadlock, increasing political street violence, and economic depression. These years were also marked by leaders who, lacking firm commitment to democracy, were willing to invoke emergency legislation as a substitute for parliamentary consent.

Suspension of Basic Civil Rights

Following the appointment of Adolf Hitler as chancellor on January 30, 1933, the leaders of the new government (a coalition of Nazis and German Nationalists) moved quickly to suspend basic civil rights for all Germans. After a suspicious fire in the Reichstag (the German Parliament), on February 28, 1933, the government claimed falsely that the fire was the signal for a communist effort to overthrow the state. It proclaimed a state of emergency in a decree that suspended constitutional civil rights and enabled Hitler to decree further legislation without parliamentary confirmation.

"Coordination"

In the first months of Hitler's chancellorship, the Nazis instituted a policy of "coordination"—the alignment of individuals and institutions with Nazi goals. Within six months, the Nazis either banned or forced into “voluntary” dissolution all other political parties, including their coalition partner, the German Nationalists.

Culture, the economy, education, and law all came under Nazi control. The Nazi regime also attempted to "coordinate" the German churches and, although not entirely successful, won support from a majority of Catholic and Protestant clergymen. The Nazis were also particularly successful in mobilizing support from among Germany's educated and professional elites, including the legal, law enforcement, education, and medical professions. The Nazis also mobilized support from among the civil service elite by making good on electoral promises to tear up the Versailles Treaty, restore Germany to the ranks of the Great Powers, bring the nation out of the depression, take back the streets from criminals and subversives, crush the communist threat, and open career opportunities for young professionals.

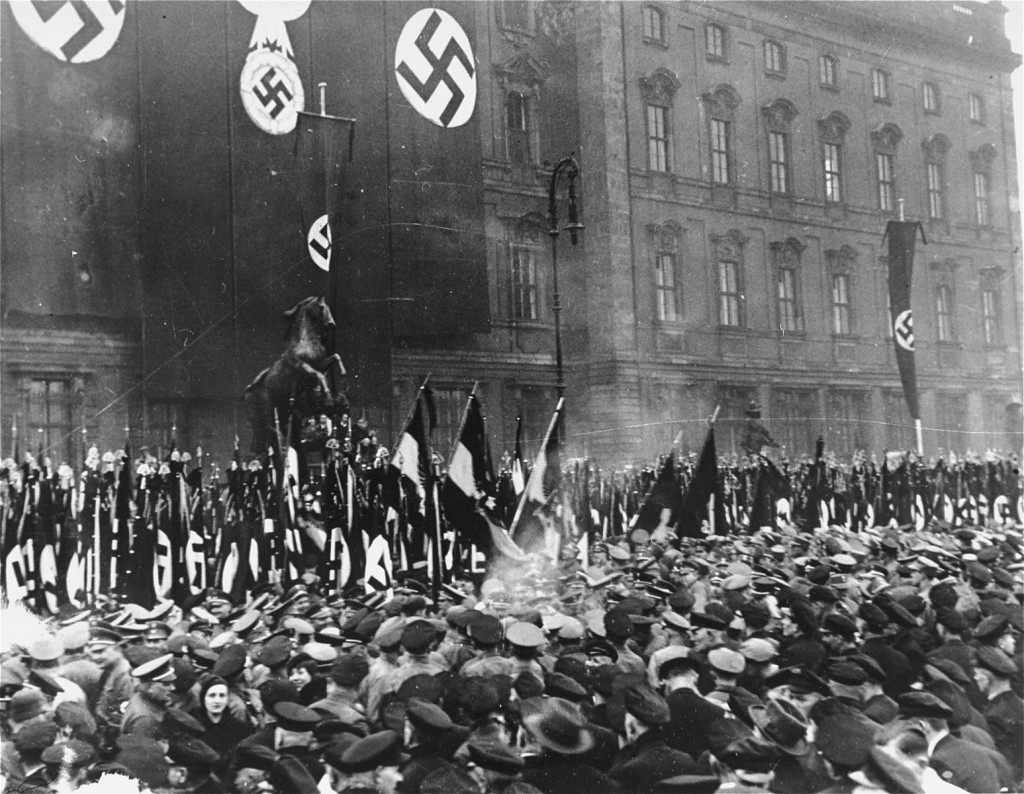

With great success, Nazi officials used extensive propaganda, carefully crafted to appeal when necessary to more general national, economic, and social goals. They aimed to appeal to convinced National Socialists and non-Nazi Germans, and also to undercut anti-Nazi sentiment.

Hitler as Führer

German president Paul von Hindenburg died in August 1934. Hitler had secured the support of the army with the Röhm Purge of June 30, 1934. He abolished the presidency and proclaimed himself Führer of the German people (Volk). All military personnel and all civil servants swore a new oath of personal loyalty to Hitler as Führer. Hitler also continued to hold the position of Reich Chancellor (head of government)

In this status, Hitler stood outside the legal constraints of the state apparatus whenever he perceived the need to adopt policies and make decisions that he deemed necessary for the survival of the German race. This extra-legal line of authority, known as the “Führer Executive” (Führerexekutiv) or the "Führer principle" (Führerprinzip) extended down through the ranks of the Nazi party, the SS, the state bureaucracy, and the armed forces. It allowed for agencies of the party, state, and armed forces to operate outside the law when necessary to achieve the ideological goals of the regime, while maintaining the fiction of adhering to legal norms.

The notion of the “Führer principle” was often misunderstood by both internal and foreign observers as well as by some Nazis themselves to mean absolute obedience to one's superiors. As the Nazi leadership understood it, the concept did embody obedience but it also involved the use of considerable imagination and initiative. This permitted an individual who was certain that he was “working towards the Führer” to go around his superior in certain circumstances where the measures he proposed or took demonstrated a better understanding of the long-term goals of the Nazi regime.

Hitler had the final say in both domestic legislation and foreign policy. Nazi foreign policy was guided by the racist belief that Germany was biologically destined to expand eastward by military force and that an enlarged, racially superior German population should establish permanent rule in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. Here, women played a vital role. The Third Reich's aggressive population policy encouraged "racially pure" women to bear as many "Aryan" children as possible. During the war, however, the Nazi regime encouraged the active engagement of German women, particularly in the occupied east, in a variety of activities. These activities ranged from welfare and charity organizations that utilized recycled clothing and household equipment taken from the Jewish victims of the Holocaust to teaching Nazi versions of European history in ethnic German schools in occupied Poland and the Soviet Union.

Nazi Ideology

As an absolute principle of national security, Nazi ideology called for the elimination of "racially inferior" peoples (such as Jews and Roma) and implacable political enemies (such as communists) from regions in which Germans lived. In their foreign policy during the 1930s, the Nazi leadership aimed from the beginning to wage a war of annihilation against the Soviet Union. The Nazi government expended significant resources during the peacetime years to prepare the German people for such a war. In the context of this ideological war, the Germans planned and implemented the Holocaust, the mass murder of the Jews, whom the Nazi leadership considered to be the primary "racial" enemy.

Resistance to the Nazi Regime

Key factors that prevented the development of organized resistance to the Nazi regime included:

- The suppression of open political dissent by the Gestapo (secret state police) and the Security Service (SD) of the Nazi party

- The considerable popularity of Hitler among the Germans

- The overwhelming support of virtually all Germans for defending the Third Reich against the Soviet Union

There was, however, some German opposition to specific policies or personalities of the Nazi state, often expressed in personal nonconformity or individual acts of defiance against Nazi ordinances. There were, in addition, two major attempts on Hitler's life. The first was carried out by a lone individual, Georg Elser, in November 1939. The second involved a small conspiracy of German military leaders, inspired by Colonel Klaus Schenk Count von Stauffenberg, who sought to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944, and replace the Nazi regime with a conservative-authoritarian regime under temporary military dictatorship.

Though other small and isolated resistance groups developed, including a loosely organized, communist-inspired resistance, the vast majority of the German people supported the Nazi regime until its collapse. Germany surrendered to the Allies on May 8, 1945. On this day, the “Third Reich” came to an end.

Terminology: "Third Reich"

The designation "Third Reich" was coined in 1922 by the romantic-conservative, völkisch-nationalist writer-intellectual Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. In his publication Das Dritte Reich (The Third Reich), Moeller envisioned the rise of an anti-liberal, anti-Marxist Germanic Empire in which all social class divisions would be reconciled in national unity under a charismatic "Führer" (leader). Moeller's "Third Reich" referred to two previous Germanic Empires: Charlemagne's medieval Frankish Empire and the German Empire under the Prussian Hohenzollern dynasty (1871-1918).