Adolf Hitler: Early Years, 1889–1921

Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) was the leader of the Nazi Party and the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. Under Hitler’s leadership, Nazi Germany perpetrated the Holocaust, the systematic persecution and murder of Europe’s Jews. Born in 1889, he became the leader of the Nazi Party in the early 1920s. During this time, Hitler was exposed to political and social ideas that later became key to Nazi ideology.

Key Facts

-

1

In his youth, Adolf Hitler was influenced by antisemitism and ethnic nationalism at school, in the press, and in political life.

-

2

As a young man, Hitler experienced World War I (1914–1918); the collapse of the German Empire and the founding of the German republic (November 1918); the spread of Communism; and the Treaty of Versailles (1919).

-

3

After World War I, Hitler became a rising star in Munich politics. There, ultranationalist, antidemocratic, anti-communist, and antisemitic ideas flourished.

Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) was the leader of the Nazi Party and the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. He is widely regarded as a symbol of evil because of the crimes committed by the Nazi German regime under his leadership. In particular, it is Hitler’s responsibility for World War II and the Holocaust—the systematic persecution and mass murder of Europe’s Jews—that has made him so infamous.

Hitler’s life is often the subject of myths and legends. Many of these stories are lurid, fantastical, or sensational. Some of the myths came from Hitler himself and the (largely) fictionalized version of his life he presented in his book Mein Kampf. Other myths came from political opponents, hoping to discredit him. Still others have evolved since his death as people have tried to understand how one man could inspire millions of people to unleash so much destruction.

Hitler’s early years were important for the development of his ideology. During this time, Hitler was exposed to the ideas that became key components of his worldview. These ideas include extreme ethnic German nationalism; racial antisemitism; opposition to liberal democracy; and anti-communism. When and why Hitler adopted an extreme and radicalized worldview remains subject to historical debate.

Myths about Hitler’s Family Background

There are two main myths about Adolf Hitler’s family background. The first is the false idea that Hitler’s grandfather was Jewish. The second is the claim that Hitler’s real last name was Shicklgruber. Neither of these myths is true.

Was Hitler’s Grandfather Jewish?

No. There is no evidence that Adolf Hitler’s grandfather was Jewish. This myth appeared as early as the 1920s.

The origin of this myth has to do with the birth of Hitler’s father. Hitler’s father, Alois, was born out of wedlock to Maria Anna Schicklgruber. Alois’s baptismal record did not include his father’s name. Although it is impossible to prove, the most likely candidates to have been Alois’s biological father (and therefore Adolf Hitler's grandfather) are the Hiedler brothers: Johann Georg or Johann Nepomuk. Johann Georg became Alois’s stepfather, and Johann Nepomuk helped raise him. In 1876, Johann Georg was officially added to Alois’s birth certificate as his father. Neither man was Jewish. There is no evidence that Maria Anna had any intimate relationship with a Jewish man.

Was Adolf Hitler’s real last name Schicklgruber?

No, Adolf Hitler’s last name was never Schicklgruber, but it was a family name. Schicklgruber was Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandmother’s last name. Because Hitler’s father Alois was born out of wedlock, he used the last name “Schicklgruber” until adulthood. In 1876, Alois changed his last name to “Hitler,” when he added his stepfather’s name to his birth certificate. “Hitler” was one spelling of the last name “Hiedler.” Alois Hitler gave this last name to his children, including Adolf Hitler.

Hitler’s Childhood and Adolescence

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, to Alois and Klara (née Pölzl) in the town of Braunau am Inn in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (today Austria). Hitler was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church. His father Alois (1837–1903) was a mid-level customs official. Klara (1860–1907) was Alois’s third wife. The couple had six children, four of whom died in infancy or childhood. Adolf Hitler’s younger sister Paula was born in 1896. Hitler also had two older half-siblings from his father’s second marriage.

The Hitler family moved several times in Adolf’s childhood. In 1898, they settled in a village on the outskirts of the Austrian city of Linz. For several years, Adolf Hitler attended school in Linz, where he struggled with his grades.

Hitler’s Exposure to German Nationalism

At school, Hitler was exposed to German nationalist ideas popular in Linz at the time. This was probably where he was introduced to the ethnic German nationalism of Georg Ritter von Schönerer. Schönerer argued that all ethnic Germans should be united in one country. He opposed the multinational Austro-Hungarian empire. Schönerer also promoted racial antisemitism.

Hitler’s Failed Artistic Dreams

Young Adolf Hitler wanted to be an artist. According to Hitler, he fought bitterly with his father, who wanted him to enter the Austro-Hungarian civil service. After his father's death in 1903, Hitler persuaded his mother to allow him to pursue his dream of becoming an artist. In the autumn of 1907, Hitler took the entrance exam to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. His application was rejected.

Hitler “the failed artist” is a popular trope about the German dictator.

Klara Hitler’s Jewish Doctor

There is a common myth that Adolf Hitler hated Jews because of a Jewish doctor who treated Hitler’s mother. There is, however, significant evidence to the contrary.

Throughout 1907, Hitler helped care for his mother, who was dying of breast cancer. Her physician, Dr. Eduard Bloch, was Jewish. Hitler and Dr. Bloch developed a good relationship. Hitler expressed his gratitude for Bloch’s help and care. Klara died in December 1907. Years later, when the Nazis took over Austria, Hitler saw to it that Dr. Bloch and his wife were exempted from many of the regime’s antisemitic policies.

Hitler’s Time in Vienna, 1908–1913

In early 1908, some weeks after his mother Klara's death, Hitler moved to Vienna. Unlike Linz, where the population was overwhelmingly German, Vienna was multiethnic, multinational, and multireligious. The Viennese population included sizable Jewish and Czech populations. Hitler remained in the city until May 1913.

Hitler’s Lifestyle in Vienna

At first, Hitler lived fairly well in Vienna. He had a generous inheritance left by his parents, and he did not work. In 1908–1909, he failed a second time to gain acceptance to the Academy of Fine Art. He lost touch with his family. By the end of 1909, Hitler’s inheritance dried up, and he fell into poverty. He was forced to live temporarily in a homeless shelter and then in a men’s home. During this time, Hitler began to paint watercolor scenes of Vienna, which he initially sold with the help of a business partner.

Hitler’s Exposure to Political Antisemitism in Vienna

For the first two years that Hitler was in Vienna, antisemitic politician Karl Lueger was the city’s mayor. Lueger was a co-founder of the Austrian Christian Social Party (Christlichsoziale Partei). As a politician, Lueger used economic antisemitism and new political tactics to gain electoral support.

Hitler later claimed that his antisemitic political ideology was formed in Vienna. He said Lueger and the city’s antisemitic newspapers partly inspired it. However, evidence from Hitler’s life indicates that this is probably not entirely true. In Vienna, Hitler had Jewish acquaintances and business associates. Based on existing evidence, Hitler did not adopt a comprehensive antisemitic ideology until after he had left Vienna. Still, it is likely that this time period did impact Hitler’s antisemitic beliefs and politics.

Hitler in Munich, 1913–1914

In May 1913, Hitler left Vienna and moved to Munich, the capital of the German state of Bavaria. Bavaria was part of the German Empire. He moved to Munich to avoid punishment for evading his military service obligation to Austria-Hungary. Hitler financed his move with the last of his inheritance. In Munich, Hitler continued to drift. He supported himself by selling his watercolors and sketches.

Hitler’s Military Service During World War I, 1914–1918

Adolf Hitler enthusiastically welcomed the outbreak of World War I in summer 1914. On August 2—as the war began— the 25-year-old Hitler attended a patriotic event in Munich on the central square, the Odeonsplatz. Years later, Hitler’s photographer Heinrich Hoffmann found a young Hitler in an image he had taken of the crowd that day. This became a popular propaganda image in Nazi Germany.

Hitler Joins the Bavarian Army

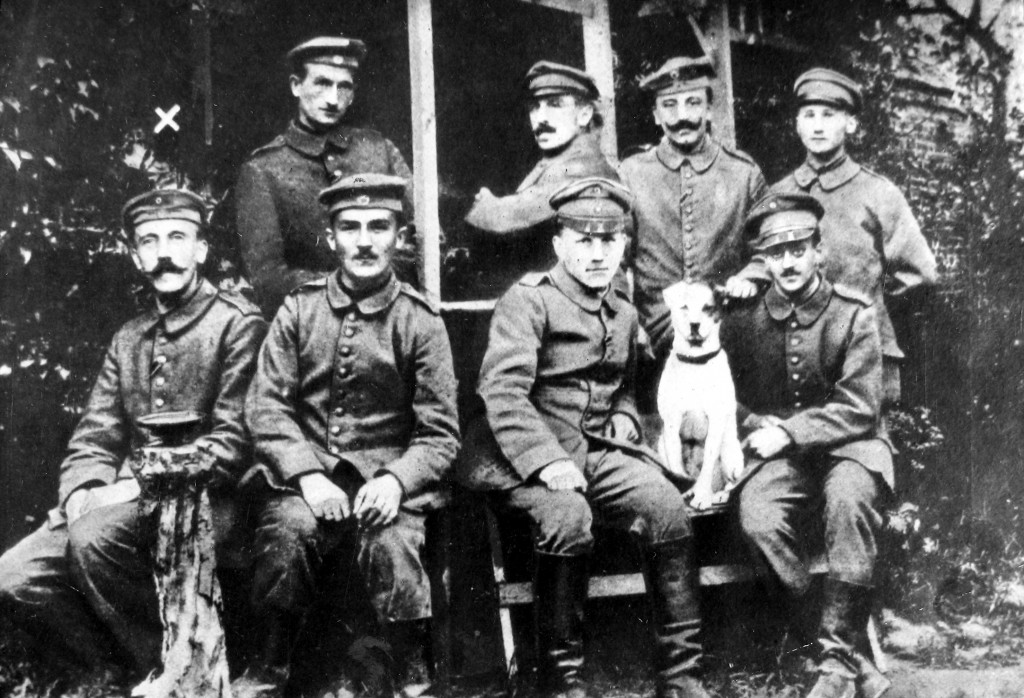

Despite being a foreign citizen, Hitler joined the Bavarian army in August 1914. During World War I, the Bavarian army was part of the German army. Hitler served in the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment. After limited, accelerated military training, the unit deployed to Belgium in fall 1914. Hitler and his unit fought at the First Battle of Ypres (October–November 1914). This was Hitler’s only frontline battle experience.

Hitler’s Military Rank and Medals

In November 1914, Hitler was promoted to Gefreiter, the second promotion rank for an enlisted soldier. This was roughly the equivalent of Private First Class in the US Army. He was never promoted again. Hitler’s rank is often mistakenly translated into English as Lance Corporal. During the war, he received several medals, including the Iron Cross 2nd Class in December 1914 and the Iron Cross 1st Class in August 1918.

Hitler as a Dispatch Runner

In November 1914, Hitler became a dispatch runner. His job was to take messages to and from regimental headquarters. He was no longer a frontline soldier. For the next four years, Hitler’s regiment fought in a number of battles in Belgium and France on the western front. During these battles, Hitler was often several kilometers behind the front lines. Nevertheless, he was lightly wounded by a shell splinter in his upper thigh in October 1916 during the Battle of the Somme.

Hitler’s Home Front Experiences

Though Hitler was on active duty with his unit during most of World War I, he also spent some time on the German home front. After he was wounded in October 1916, he stayed in an army hospital near Berlin for about two months. In both Munich and Berlin, Hitler witnessed the widespread hunger among German civilians in the winter of 1916–1917 caused by a poor harvest and wartime food blockades. A year and a half later, while on leave in September 1918, Hitler observed the complete collapse of morale on the German home front. These experiences made a lasting impression on Hitler and later shaped decisions he made about food supply during World War II.

The Final Months of World War I

In October 1918, Hitler was wounded in a mustard gas attack. He was sent to the Pasewalk military hospital. News of the November 11, 1918 armistice, the overthrow of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the German revolution reached him while he was recovering. Hitler’s disgust and dismay at the armistice and the fall of the German empire would later become an important part of his mythos and ideology.

Hitler’s Experiences in Munich after World War I

Even though most World War I soldiers quickly demobilized, Hitler chose to remain in the Bavarian military after the war ended. Without family, friends, a place to live, or job prospects, he had nowhere else to go. Hitler stayed in the peacetime Bavarian military from fall 1918 until the end of March 1920.

Political Changes in Munich 1918–1919

When Hitler returned to Munich in late November 1918, Munich was in the midst of political changes. On November 7–8, revolutionaries in Bavaria had overthrown Bavarian King Ludwig III and established a democratic republican government. From November 1918 to February 1919, the leader of the new Bavarian government was socialist Kurt Eisner, who was Jewish. Eisner was assassinated in February 1919. His successor Johannes Hoffman was eventually driven out of the city in an attempted Communist takeover. In April–May 1919, the Bavarian Soviet Councils Republic, a Communist government, took over the city. With the help of neighboring states and militias, Hoffman’s government suppressed the Bavarian Soviet Republic. An anti-Communist reaction followed, in which hundreds of people were killed.

Throughout all these political changes, Hitler continued to serve in the Bavarian military. He chose to do so despite having the option to be decommissioned. This means that Hitler—who would shortly become known for his avowed opposition to parliamentary democracy and Communism—had voluntarily served as a soldier for both types of governments.

Antisemitism in Postwar Munich

During and after World War I, antisemitism was on the rise throughout Germany. Many Germans blamed all Jews for Germany losing World War I, for the revolution in November 1918, and for the spread of communism.

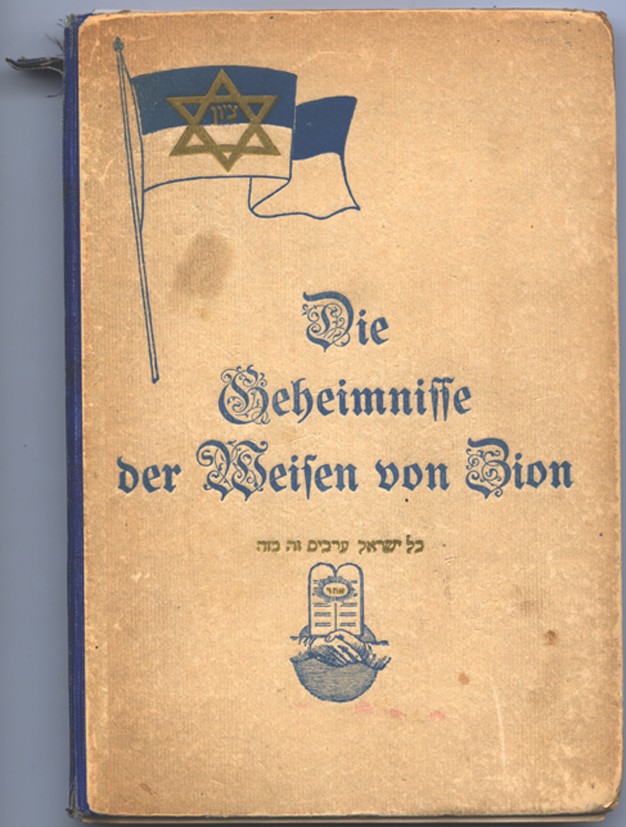

Hitler experienced this moment of heightened antisemitism in postwar Munich. Munich had become a hotbed of anti-Jewish sentiments. In Munich, antisemitism escalated in the summer and fall of 1919 in response to world events. First, many people in Munich and beyond scapegoated Jews for the actions of the communist Bavarian Soviet Republic. Popular anger against the Treaty of Versailles also took on an antisemitic tone. In 1919, an antisemitic conspiracy theory publication, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, appeared in German translation. In the months and years that followed, Adolf Hitler adopted and spread many of the antisemitic ideas and conspiracy theories common in postwar Munich and Germany at this time.

In these circumstances, new, radical right-wing antisemitic movements grew in Munich. And it was in this setting that Hitler became known for his skills as a dynamic political speaker.

Hitler’s First Antisemitic Statements and Speeches

In summer 1919, Hitler joined the Information Office of the Bavarian Military Administration. This military office gathered intelligence on political parties in Munich and provided anti-Communist “political education” for the troops. In July, Hitler attended an anti-Communist propaganda training course. There, he heard lectures on history and politics that likely influenced some of his thinking. That summer, Hitler realized he was a gifted public speaker and began to hone his talent. In August 1919, he made his first antisemitic political speeches for soldiers.

Impressed with Hitler’s skills as a communicator, his supervisor entrusted him with responding in writing to a query from a student about the so-called “Jewish Question.” In a letter of September 16, 1919, Hitler identified Jews as a race (“Rasse”). He repeated lies about Jews rooted in economic, nationalist, and racial antisemitism. In the letter, he also called for a strong, nationalist government that would remove Jewish people completely from Germany.

Rise to Leadership of the Nazi Party

Related to his job in the Information Office, Hitler attended the meeting of the small German Workers’ Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or DAP) on September 12, 1919. During the meeting, Hitler claimed he gave an impromptu speech, which so impressed the party’s leadership that they encouraged him to join. Within a month, Hitler had joined the DAP with member number 555. Hitler later falsely claimed his membership number was seven.

Hitler gave his first official speech for the DAP on October 16, 1919, at a beer hall. Due to his speaking abilities, Hitler quickly rose into the DAP leadership ranks. He helped DAP leaders write the party’s political program. This program was announced by Hitler at a large public meeting on February 24, 1920, at the Munich Hofbräuhaus. Shortly afterwards, the DAP changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or NSDAP). It became known in English as the Nazi Party.

At the end of March 1920, Hitler left the Bavarian military. He moved into a small rented room, near the city center. From this point forward, he devoted himself fully to politics. He earned money from his political speeches, as well from the Nazi Party and its benefactors.

By mid-1921, Hitler established himself as the leader of the Nazi Party. In this role, Hitler would become one of the most important and destructive political figures in history.