Eyshishok: The Annihilation of a Jewish Community

Nazi Germany and its allies and collaborators perpetrated mass shooting operations targeting Jews in occupied eastern Europe. This is sometimes known as the Holocaust by bullets. About 2 million Jews were murdered in these mass shootings and associated massacres. In this way, German authorities destroyed Jewish communities in more than 1,500 villages, towns, and cities in eastern Europe. Eyshishok was one of these communities.

Key Facts

-

1

Before World War II, Eyshishok was a predominantly Jewish town located in northeast Poland. During the war, Eyshishok changed hands a number of times.

-

2

On September 25 and 26, 1941, German Einsatzkommando 3 and Lithuanian auxiliary forces shot and killed approximately 3,500 Jews, including most of the town’s residents.

-

3

The Jews of Eyshishok are remembered in the Tower of Faces, an exhibit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The tower features more than 1,000 photographs of life before the Holocaust.

The Jewish community of Eyshishok has become a symbol of the lives and communities that were destroyed in the Holocaust. The people of the town of Eyshishok are memorialized in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s exhibit the Tower of Faces.

Historically, Eyshishok has been called by a number of different names, including Ejszyszki (Polish) and Eišiškės (Lithuanian). Eyshishok (איישישאָק) is the Yiddish name for this town and was the name usually used by the Jewish community who lived there. Today, Eyshishok is located in Vilnius County, Lithuania, near the Lithuanian-Belarusian border. However, when World War II began, this area was part of Poland.

Eyshishok and the surrounding region have a long history of diversity. It was multireligious, multiethnic, and multilingual. This is partially because the region has changed hands multiple times in the last three hundred years. Historically, the region was home to different ethnic groups who spoke many different languages: Belarusians, Jews, Lithuanians, Poles, Tatars, and others. It was also a multi-religious region that included Catholics, Jews, Muslims, and Orthodox Christians.

Before the Holocaust, Eyshishok was considered a shtetl. Shtetl is a Yiddish word that typically describes a small market town in eastern Europe with a majority Jewish population. In the late nineteenth century, Eyshishok’s population was around 2,000–3,000 people. It was 70 percent Jewish. The other 30 percent of townspeople were primarily Poles, many of whom were Roman Catholic. In and around Eyshishok, most of the peasants were ethnically Polish. But, Lithuanians, Tatars, and Belarusians lived in the region and interacted with the people of Eyshishok.

The Jewish Community in Eyshishok

There was a documented Jewish community in Eyshishok for more than 250 years before the Holocaust. In the interwar era, Eyshishok’s Jewish community numbered around 2,000 people. The exact population fluctuated as a result of war and emigration.

For the Jews of Eyshishok, life in the town was strongly rooted in Jewish tradition. There were many Jewish cultural organizations, educational activities, and relief societies in the town. Near the main square, there was a synagogue complex. In the synagogue courtyard (shulhoyf), there were two places designated for Torah study (the old and new batei midrash), and a ritual bath (mikvah). There was also a Hebrew day school.

Economic life in Eyshishok revolved around the market square and the weekly market that was held there on Thursdays. The marketplace square in the center of town was home to many of the town’s shops and businesses. Clientele included the Jewish and Polish townspeople and the Polish peasants. Many of the town’s Jewish families managed and owned small businesses, such as bakeries, a photography studio, taverns, and grocery stores. Some Jews worked as shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths, butchers, or in other services. Many of these businesses struggled in the 1920s and 1930s. At that time, the Polish government’s economic policies negatively impacted Jewish-owned commerce and trade.

While the Jewish community of Eyshishok was close knit, it was also increasingly diverse. In the 1920s and 1930s, the development of infrastructure in the region connected Eyshishok to the outside world with increasing regularity. In the 1920s, the Polish government built a paved highway that passed through Eyshishok. A Jewish family operated a Shell gas station in the center of town where buses refueled. In 1931, the town had electricity for the first time.

Not everyone in Eyshishok’s Jewish community shared the same political views or religious approach. The generational and political divides that were causing strife throughout much of Europe and North America were also noticeable in Eyshishok. Younger generations moved away from shtetl traditions. Many were attracted by contemporary life in larger cities and cultural centers, like Vilna (Wilno/Vilnius). Some were even attracted to modern, secular political movements, such as Communism.

Interethnic Relations in Eyshishok

In Eyshishok, Jews did not live in isolation from the other groups in the area. Jews and non-Jews in Eyshishok lived near each other and worked together on a daily basis. Many had close relationships. Some Polish peasants even kept a separate pot for Jewish visitors who kept kosher (i.e., practiced strict dietary standards according to Jewish religious law).

For instance, the Kabaczniks were one of the more prominent Jewish families in town. They ran a tannery and wholesale leather business. Many of their employees were Polish, including their maid who spoke Yiddish with the family. The Kabaczniks were very close with some of the Polish families in town. Miriam Kabacznik recalled,

It was a normal life. A normal, nice life. We knew each other. It was friendly. It was welcome. We never had a door locked. The doors were always open and unlocked. And we had a lot of friends among the non Jews. That they were always welcome in the house. And coming in.

But there were also difficulties between individuals and groups in Eyshishok. Interactions were, at times, marked by prejudices and resentments. These difficulties were often rooted in religious and class differences. For example, fights often broke out between peasants and townspeople on market day. Some of the Jewish children remembered schoolyard disagreements, in which their Polish classmates used antisemitic slurs.

World War II altered existing relationships in Eyshishok. Occupying forces pitted groups against each other. In doing so, they up-ended long-standing ethnic and class dynamics. The brutality of the Nazi occupation would be particularly destabilizing and destructive.

Eyshishok and the Course of World War II

World War II began in Europe in September 1939 with the German invasion of Poland. Two weeks later, the Soviet Union invaded and occupied eastern Poland. This Soviet-occupied region included Eyshishok. In October 1939, the Soviet Union transferred Eyshishok and the surrounding region to Lithuania.

Eyshishok as a Lithuanian Border Town (1939–1940)

Beginning in October 1939, Eyshishok was located in Lithuania. It was just a few miles from the border between Lithuania and Soviet-occupied Poland.

As a border town, Eyshishok served as a transit point for Jewish refugees. At the time, Jews and others could still escape German and Soviet-occupied Poland through Lithuania. Many people crossed the border illegally, avoiding the Lithuanian border police. Local peasants often guided refugees across the border and onto Eyshishok and then Vilna. These refugees needed food, housing, and directions. The Eyshishok rabbi, Szymen Rozowski, formed a committee to assist them.

The Jews of Eyshishok learned from these refugees about the Nazi persecution of Jews in German-occupied Poland.

Soviet Occupation of Lithuania (Summer 1940–June 1941)

In the summer of 1940, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed Lithuania. This meant that Eyshishok once again came under Soviet control. The Soviets transformed the administration of Lithuania, putting Communists in power at the regional and local levels. The Soviets deported thousands of people to Siberia.

As a Communist state, Soviet-controlled Lithuania opposed religion and free enterprise. The new government implemented harsh policies against many people in occupied Lithuania, including both Jews and non-Jews. The Communist authorities nationalized private property. In Eyshishok, some of the more well-to-do residents lost their businesses and homes in this way. The government also shuttered some religious institutions.

In Eyshishok, local Jews who supported the Communists carried out these policies within their own community. They forced Rabbi Rozowski to move out of his home and closed the Hebrew day school. However, the synagogue stayed open, and the community still celebrated religious holidays.

In Lithuania, many Jews and non-Jews rejected Soviet control. They opposed the nationalization policies of the new Communist authorities. Some Lithuanians blamed Jews for Soviet policies. The Soviet occupation created new resentments that were often built on older prejudices.

German Occupation of Lithuania (June 1941–1944)

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, including Soviet-occupied Poland and Lithuania. The Nazis waged a brutal campaign against Communism and executed people who had worked for the Soviet occupiers. Many Lithuanians were glad to see the end of the Soviet occupation and hoped for the return of an independent Lithuania.

Some anti-Communist Lithuanians welcomed the arrival of the German military. New nationalist Lithuanian militias formed and subsequently joined the German campaign against Communists. In some cases, these militias also attacked Jews and carried out pogroms. German propaganda encouraged Lithuanians to blame the Jews for Soviet rule and German authorities instigated many of the pogroms.

In August 1941, the Germans installed a German civilian administration in occupied Lithuania. The Germans appointed Lithuanians to many administrative positions.

The German Occupation of Eyshishok

In late June 1941, the German army arrived in Eyshishok. But they stayed only a matter of weeks.

When the military left, a civilian German occupation administration took over the town and surrounding region. As in many parts of Europe, the Germans relied on local systems and collaborators to govern. Thus, Germans were in command of Eyshishok, but their local representatives included Lithuanians.

German occupation forces in Eyshishok subjected Jews to forced labor, violence, and public humiliation. They required Jews to wear a Star of David badge. They humiliated religious Jewish men by cutting their beards. They banned Jews from walking on the sidewalks. The Germans also forced Eyshishok’s Jews to surrender their valuables.

In addition, the Germans ordered the creation of a Jewish council (Judenrat) in Eyshishok. The council had to enforce German policies. Its members also had to ensure that forced labor demands set by the occupiers were fulfilled. Among other duties, the Jewish council had to supply the German occupiers with food.

The Mass Murder of the Jews of Eyshishok, September 1941

The Holocaust in Eyshishok was part of the larger story of the Holocaust in Lithuania. The Nazis carried out the mass murder of Jews in Lithuania at a shockingly rapid pace. At the time of the Nazi occupation, about 200,000 Jews lived in Lithuania. In just six months, the Germans, with the help of Lithuanian collaborators, murdered 150,000 Jews.

A German SS and police unit called Einsatzkommando 3 organized many of the massacres in German-occupied Lithuania. In particular, they massacred Jews in communities around the cities of Kovno (Kaunas) and Vilna. Einsatzkommando 3 was a small unit and could not perpetrate mass murder alone. They recruited members of nationalist Lithuanian militias into auxiliary units. It was usually these units that carried out the massacres under German supervision.

Among those murdered in German-occupied Lithuania in the summer and fall of 1941 were the Jews of Eyshishok.

Prelude to Massacre

In September 1941, Einsatzkommando 3 and its Lithuanian auxiliaries started carrying out massacres near Eyshishok.

Local peasants warned the Jews of Eyshishok about what was happening. They told them that massacres of Jews were taking place in nearby towns, including in the town of Varėna on September 10, 1941. Varėna was only about 20 miles west of Eyshishok. While some Jews dismissed these warnings, Rabbi Rozowski took them seriously. Rozowski called a meeting. He encouraged the Jewish community to take up arms in self-defense. There was hesitancy and disagreement among the Jewish residents about the best course of action.

Less than two weeks later, mass murder came to Eyshishok.

Sunday, September 21, 1941: The Round Up

Sunday, September 21, 1941 was the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and one of the holiest days in Judaism.

That morning, notices appeared in town. The German administration was ordering the Jews of Eyshishok to surrender their remaining valuables and to gather in the synagogue that evening. Armed strangers appeared in town. Many Jews tried to hide their valuables, secure hiding places, and convince loved ones to flee.

Later that day, Lithuanian auxiliary policemen rounded up the Jews of Eyshishok. They forced the Jews to go to the synagogue and the batei midrash (places designated for Torah study). Some Jews ignored the order and tried to run or hide with their non-Jewish neighbors, employees, and friends. The Lithuanian auxiliaries cordoned off the town. They tried to prevent people from leaving.

Monday–Wednesday, September 22–24, 1941: Detention

For at least three days, the Jews remained crowded in the synagogue and the two batei midrash. They were held without food or water. There were no bathrooms. Hundreds of Jews were brought from other towns, including from the nearby town Valkininkai (Olkieniki in Polish).

German Einsatzkommando 3 often created improvised detention centers that lasted for only a matter of days. Detaining Jews in this way was typical of the Holocaust in this area. The purpose was to concentrate the Jews of a community or district prior to their murder.

Sixteen year old Zvi Michaeli and his family were among those packed into the synagogue. Years later, he recounted how people around them started to panic. They began to yell and scream. Children were crying. People stepped on each other as they made their way to the makeshift bathroom in the entryway. The rabbi began to lead the people in prayer. The synagogue was filled with the sounds of simultaneous yelling, crying, and praying.

Conditions worsened as more and more Jews from the surrounding region were forced into the synagogue complex. For two days and three nights, the Jews were held inside the tightly packed synagogue.

On Wednesday, September 24, the perpetrators took the Jews outside. They led the Jews a few blocks away to the horse market area. To get there, they passed through the middle of town. Some of their neighbors gathered to watch and even cheer. At the horse market the Jews were guarded by Lithuanian auxiliary policemen and their dogs.

Thursday, September 25, 1941: The Massacre of Jewish Men

On the morning of Thursday, September 25, the perpetrators selected approximately 250 young and fit men from among the thousands gathered at the horse market. The Jews were told that these men were going to build a ghetto. But instead, the Lithuanian auxiliaries took them to the old Jewish cemetery. There, they shot them.

The Jews being held at the horse market could hear the sounds of the massacre. According to Zvi Michaeli, some of their non-Jewish neighbors approached the market fence and urged the Jews to run and save themselves. Others, focused on material gain, asked the Jews to toss their valuables over the fence.

More and more men and boys were led in groups to the old Jewish cemetery. There, Lithuanian auxiliary forces made them undress. While Germans watched, the Lithuanian auxiliaries shot the Jewish men into a pre-existing pit. Women and children remained in the horse market during the massacre of the men.

Zvi Michaeli was in line to be shot with his father and younger brother. During the shooting, a bullet only grazed him. But a bullet hit his father whose body landed on top of Zvi. Zvi remembered,

But I’m still conscious. I know what’s going on. I feel I am not dead… I’m still alive. And for a longer time, I feel his body on me. And he got heavier, and heavier and heavier. I feel I’m choking. I can’t take it anymore. And I feel his blood all over me. It was hard to slide out from [under] him. But I managed somehow….

Eventually, Zvi crawled out of the mass grave and fled.

Friday, September 26: The Massacre of Women and Children

On Friday, September 26, the perpetrators began to massacre the women and children. They drove them in wagons about one mile to a gravel pit. The pit was located behind a Catholic cemetery. The Lithuanian auxiliaries separated the women and children. They forced the women to undress. And they began shooting them into a mass grave. They raped many of the younger women. Then they brutally killed the children.

Leon Kahn and his brother were hiding in the cemetery. They witnessed the murder of the women and children. Leon later remembered, “It wasn’t a matter just of executing and killing people. It was a matter of savagery.”

Documenting the Massacre: The Jäger Report

In December 1941, Karl Jäger, the commander of Einsatzkommando 3, bragged that his unit had solved “the Jewish problem for Lithuania” (“das Judenproblem für Litauen”).

In an infamous report to Berlin, he listed the locations, dates, and sizes of more than one hundred massacres. Einsatzkommando 3 had conducted most of these massacres in German-occupied Lithuania. The report lists the date for the massacre in Eyshishok (spelled Eysisky in the report) as September 27. It is unclear whether this was a mistake, or perhaps a reflection of the day the massacre was completed or reported.

Jäger informed his superiors in Berlin that his unit had massacred, in total, 137,346 Jews. Behind each statistical entry in the Jäger Report is the savage murder of individuals and the destruction of Jewish communities in Lithuania and Belarus.

The Jäger Report details that 3,446 Jewish people were murdered in Eyshishok. Among them were 989 men, 1,636 women, and 821 children. Survivor accounts suggest that the number killed may be even higher.

Rescue and Survival in Eyshishok

Surviving the Massacre

Hundreds of Eyshishok Jews initially survived the massacre by hiding and fleeing. The chaos of these days presented opportunities for escape. Some refused to gather in the synagogue on the evening of September 21. Others managed to sneak away from the synagogue or the horse market in the days that followed. According to survivor testimonies, in at least two instances Lithuanian auxiliaries helped Jews escape.

Those who fled and hid relied on help from non-Jews. They turned to their Polish neighbors, friends, and employees for help. These Poles helped sneak Jews away from the Lithuanian and German guards. They hid people in their homes. And they provided them with clothes to disguise them as peasants. For example, after Zvi Michaeli crawled out of the mass grave, he went to the farm of family friends who were Polish. He arrived at their door naked and covered in blood. They helped clean and care for him.

But surviving the massacre did not guarantee the survival of Eyshishok’s remaining Jews. The German occupation and mass murder of Europe’s Jews had just begun.

Rescue and Survival After the Massacre

After the massacre, it was not safe for Eyshishok’s Jews to remain in the town.

Many fled about nine miles south to the town of Raduń, where they had friends and family. Raduń was located in a different German administrative area than Eyshishok and in September 1941, mass killing was less systematic in that area. However, many of those who fled to Raduń did not survive the Holocaust. They were killed in May 1942 when the Germans liquidated the Raduń ghetto.

Other Jews hid in the countryside, trying to avoid detection. They spent varying periods of time with Polish friends or strangers. Some joined partisan units in the nearby forests.

As the war progressed, life in and around Eyshishok became more and more difficult. Under the German occupation, penalties for helping Jews were severe. In the Eyshishok region, those who had been willing to help Jews in the moment of crisis were not necessarily willing or able to risk long-term aid.

Nevertheless, a few people did help at great risk. For example, Kazimierz Korkuć (external link), a Polish farmer, hid sixteen Jews on his farm in a nearby village. Among those he hid were his friends, the Sonensons, including a young Yaffa Eliach (née Sonenson). Antoni Gawryłkiewicz (external link), a young Polish shepherd, regularly helped this group of Jews while they were in hiding by providing them with food and clothing. He also served as a courier between them and partisans in the area.

Suspected of helping Jews hide, Korkuć and Gawryłkiewicz were arrested, interrogated, and beaten by occupation officials. However, neither man admitted to hiding Jews. Korkuć was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations in 1973. Gawryłkiewicz was recognized in 1999.

Not all of those who escaped the initial massacre in Eyshishok survived the Holocaust. In addition to those murdered in the Raduń ghetto, others were killed when their hiding places were discovered or while fighting as partisans.

Aftermath

Between July and October 1944, the Soviet Red Army drove the Germans out of Lithuania and reoccupied the country. The Red Army reconquered Eyshishok on July 13, 1944. At this time, Jews surviving in hiding began to return to the town.

In the end, only a few dozen Jews from Eyshishok survived the Holocaust.

Those who survived were haunted by the memories of late September 1941 and the years that followed. Zvi Michaeli remembered,

I never survived emotional[ly] the Holocaust. I am a split man remaining, up till now. Because my body is still in the grave, my father over me, the blood of my brother, of my father is still on my back. They are with me. They’re accompanying me in my daily life.

Memorialization in the Tower of Faces

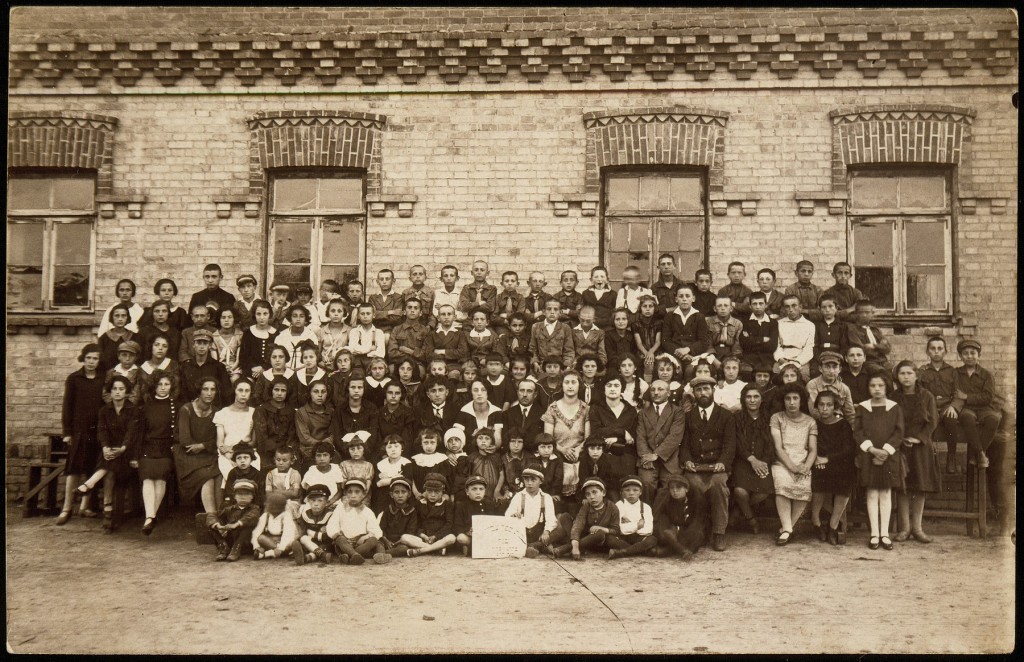

The Jews of Eyshishok are remembered in the Tower of Faces, an exhibit at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The tower features more than 1,000 photographs. These images attest to the rich cultural and community life created by the shtetl residents before the Holocaust.

The photos were collected by Yaffa Eliach (née Sonenson), herself a survivor from Eyshishok. Eliach was the granddaughter of Yitzhak and Alte Katz, who owned the town’s photo studio and captured many of the images on display. Eliach traveled around the world for 15 years in search of the photos. Of her motivation for the Tower, she wrote:

What kind of memorial could possibly transcend those images of death and do justice to the full, rich lives those people had lived, I wondered…I decided I would set out on a path of my own, to create a memorial to life, not to death.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

The history of the region around Eyshishok is complex. From 1569–1795, Vilna and the surrounding area, including Eyshishok, were part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the late 1700s, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was forcibly dissolved and partitioned between the Kingdom of Prussia, the Austrian Empire, and the Russian Empire. From 1795 until the end of World War I, Eyshishok was in the Vilna governorate of the Russian Empire. With the collapse of the Russian Empire during World War I, Poland and Lithuania were reconstituted as independent states. Both states claimed Vilna and the surrounding region, including Eyshishok. The exact border remained contested until 1922, when Vilna and Eyshishok became part of the Second Polish Republic. At that time, Eyshishok was located in the Nowogródek Voivodeship.

-

Footnote reference2.

Miriam Kabacznik Shulman, interview by Randy M. Goldman, July 23, 1996, part 1, transcript and recording, The Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, RG-50.030.0375, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn504868.

-

Footnote reference3.

Zvi Michaeli, interview by Irene Squire, February 5, 1996, interview 11771, segments 62–63, transcript and recording, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation.

-

Footnote reference4.

Leon Kahn, interview by Fran Starr, December 5, 1996, interview 23999, segment 11, transcript and recording, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation.

-

Footnote reference5.

Zvi Michaeli, interview by Irene Squire, February 5, 1996, interview 11771, segments 166–167, transcript and recording, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation.

-

Footnote reference6.

Yaffa Eliach, There Once Was a World: A 900-Year Chronicle of the Shtetl of Eishyshok (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1998), 3.