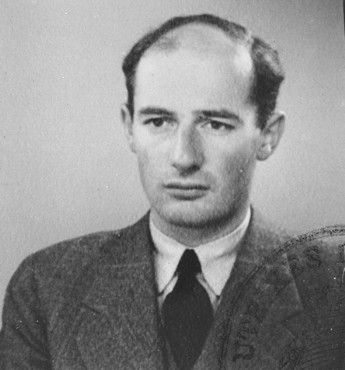

Raoul Wallenberg and the Rescue of Jews in Budapest

Key Facts

-

1

Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg led one of the most extensive and successful rescue efforts during the Nazi era. His work with the War Refugee Board saved thousands of Hungarian Jews.

-

2

Shortly after arriving in Budapest, Hungary, in July 1944, Wallenberg began distributing certificates of protection to Jews. During the autumn of 1944, Wallenberg repeatedly intervened to secure the release of bearers of certificates of protection and those with forged papers.

-

3

Wallenberg was posthumously granted American citizenship in 1981, and in 1985 the portion of the street on which the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC is located was renamed in his honor.

Background

Raoul Wallenberg was born on August 4, 1912, in Stockholm, Sweden.

After studying in the United States in the 1930s and establishing himself in a business career in Sweden, Wallenberg was recruited by the US War Refugee Board (WRB) in June 1944 to travel to Hungary. Given status as a diplomat by the Swedish legation, Wallenberg's task was to do what he could to assist and save Hungarian Jews.

Wallenberg Arrives in Budapest

Assigned as first secretary to the Swedish legation in Hungary, Wallenberg arrived in Budapest on July 9, 1944. Despite a complete lack of experience in diplomacy and clandestine operations, he led one of the most extensive and successful rescue efforts during the Holocaust. His work with the WRB prevented the deportation of thousands of Hungarian Jews.

Hungary had been an ally of Germany, but German defeats and mounting Hungarian losses led Hungary to seek an armistice with the western Allies. To forestall these peace feelers, German forces occupied Hungary on March 19, 1944, and forced the Hungarian head of state, Miklos Horthy, to appoint a pro-German government under Dome Sztojay. The Sztojay government was prepared not only to continue the war but also to deport Hungarian Jews to German-occupied Poland. Shortly after the occupation, Hungarian officials began to round up Hungarian Jews and to transfer them into German custody.

By July 1944, the Hungarians and the Germans had deported nearly 440,000 Jews from Hungary, almost all of them to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the SS killed approximately 320,000 of them upon arrival and deployed the rest at forced labor in Auschwitz and other camps. Nearly 200,000 Jews remained in Budapest; the Hungarian authorities intended to deport them as well, in compliance with German requests.

Rescue Activities

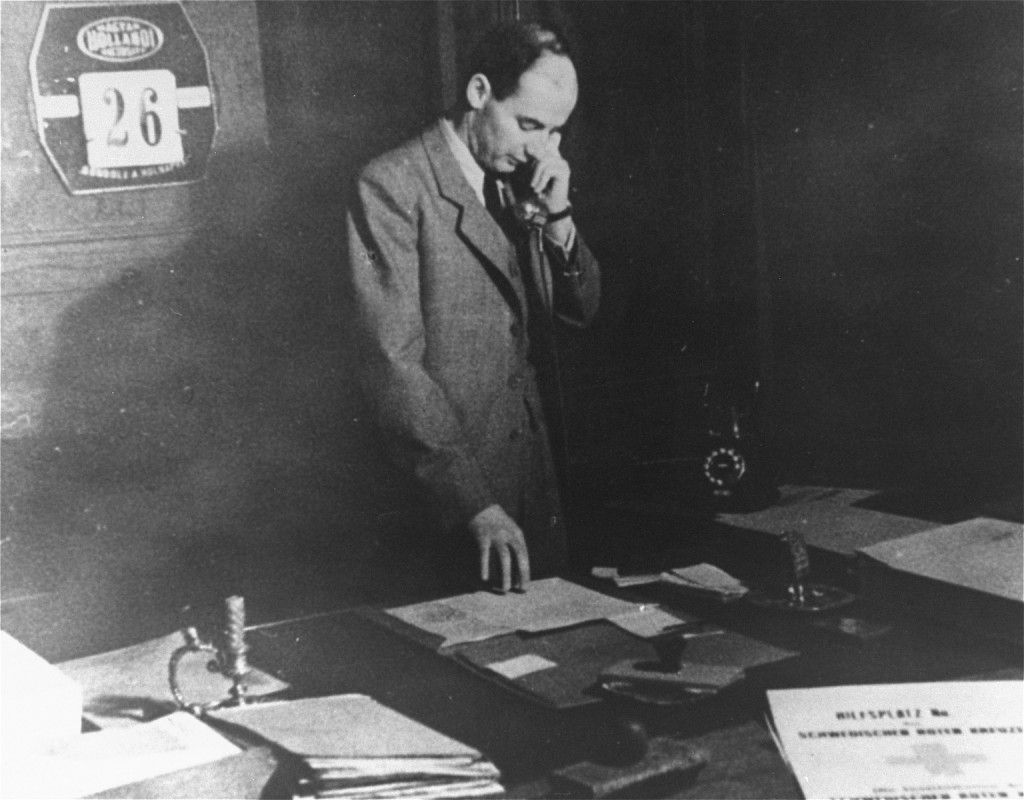

With authorization from the Swedish government, Wallenberg began distributing certificates of protection issued by the Swedish legation to Jews in Budapest shortly after his arrival in the Hungarian capital. He used WRB and Swedish funds to establish hospitals, nurseries and a soup kitchen, and to designate more than 30 “safe” houses that together formed the core of the "international ghetto" in Budapest. The international ghetto was reserved for Jews and their families holding certificates of protection from a neutral country.

After the Hungarian fascist Arrow Cross movement seized power with the help of the Germans on October 15, 1944, the Arrow Cross government resumed the deportation of Hungarian Jews, which Horthy had halted in July before the Budapest Jews could be deported. As Soviet troops had already cut off rail transport routes to Auschwitz, Hungarian authorities forced tens of thousands of Budapest Jews to march west to the Hungarian border with Austria. During the autumn of 1944, Wallenberg repeatedly—and often personally—intervened to secure the release of those with certificates of protection or forged papers, saving as many people as he could from the marching columns.

Wallenberg's colleagues in the Swedish legation and diplomats from other neutral countries also participated in rescue operations. Carl Lutz, the consul general in the Swiss legation, issued certificates of emigration, placing nearly 50,000 Jews in Budapest under Swiss protection as potential emigrants to Palestine. Italian businessman Giorgio Perlasca posed as a Spanish diplomat. Closely assisted by Laszlo and Eugenia Szamosi, Perlasca issued to many Jews in Budapest certificates of protection for nations whose interests neutral Spain represented and established safe houses, including one for Jewish children.

After the Liberation of Budapest

When Soviet forces liberated Budapest in February 1945, more than 100,000 Jews remained, mostly because of the efforts of Wallenberg and his colleagues.

Wallenberg was last seen in the company of Soviet officials on January 17, 1945, as the Red Army besieged Budapest. He was presumably detained on suspicion of espionage and subsequently disappeared. A Soviet government report in 1956 suggested that Wallenberg had died on July 17, 1947, while imprisoned by Soviet authorities at the infamous Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. Subsequent eyewitness sightings of Wallenberg in the Soviet penal system after 1947 have called this statement into question. The exact date and circumstances of Wallenberg’s death are unknown and may never be clarified. In October 2016, 71 years after his disappearance, Swedish officials formally declared Wallenberg legally dead.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have influenced Wallenberg and other rescuers in Hungary in 1944?

Consider Wallenberg’s varied methods of rescue. What other individuals and organizations were involved to help these actions achieve success?

The deportation of the Jews of Hungary was carried out principally by Hungarians. Why would many Hungarians support and participate in this systematic mass movement of people?