How did the Nazis and their collaborators implement the Holocaust?

When Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler became German chancellor on January 30, 1933, no step-by-step blueprint for the genocide of Jews as a “race” existed. After the outbreak of World War II, millions of Jews came under Nazi control. Nazi policy extended from persecution to ghettoization and ultimately to systematic mass murder.

Learn about the staggering extent of the resources and cooperation required to implement the "Final Solution" and the active participation of governments, societies, and individuals across Europe.

See related articles for background information related to this discussion.

More than eight years separated the Nazi regime’s assumption of power in 1933 and the systematic mass murder of Jews beginning in 1941.

Persecution of Jews in the 1930s

From 1933 to 1939, Nazi leaders aimed to roll back the legal status German Jews had enjoyed since 1871 as full citizens. They sought to drive Jews from the economy and make life so difficult for Jews that they would leave Germany. During World War II (1939–1945) and especially after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Nazi policy turned murderous. Larger numbers of Jews also fell under Nazi control as a result of German military conquests and alliances.

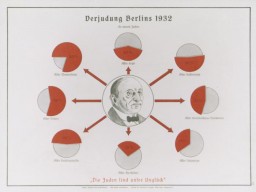

The Nazi persecution of Jews developed in several “stages” in Germany from 1933 to 1939. The Nazis used a combination of laws and decrees, propaganda, intimidation, and violence to segregate Jews from German society, remove them from the economy, and force them to leave the country.

In April 1933, soon after Hitler assumed dictatorial powers, the Nazis organized a boycott of Jewish businesses. A week later they passed a law to purge the civil service of “non-Aryans” and political opponents of the regime. In addition, Jews were socially isolated. Professional associations, sports clubs, and other civic groups fell in line with “the spirit of the times” by expelling “non-Aryans.”

Individual Jews were also victims of assaults and threats of violence by SA men, Hitler Youth, and other Nazi activists who flexed their power with little fear of interference by the police or courts. Pervasive propaganda demonizing Jews—newspaper articles and images, radio speeches, and publicly displayed signs—promoted Nazi leaders’ efforts to ensure that the many Germans who were not Nazis would remain indifferent to the plight of their Jewish neighbors.

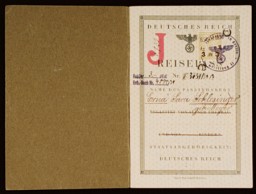

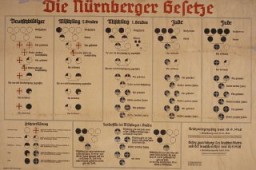

Persecution intensified with the Nazi dictatorship’s proclamation of the Nuremberg Laws in September 1935. “The Reich Citizenship Law” stated that only people with pure German blood could be German citizens. “The Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor” outlawed marriage and sexual relations between full citizens and mere subjects. Official legal commentators later also applied these laws to Roma and Sinti, Black people, and others declared a threat to the “national community” of “German-blooded” people.

In late 1937, Nazi leaders stepped up the systematic seizure of Jewish property, money, and valuables. They aimed both to pay for the state’s massive re-armament program and to incite the exodus of Jews—the “enemy within.”

Several events in 1938 left no doubt that Jews no longer had a future in Germany. These events included the expulsion of foreign Jews, including 18,000 Polish Jews, and the Nazi terror unleashed on Austrian Jews after the German annexation of Austria (the Anschluss) in March 1938 and during the November 1938 pogrom (Kristallnacht). The nationwide pogrom resulted in the murder of at least 91 Jews and the deaths of hundreds of others in concentration camps following the mass arrests of Jewish men. Up to 30,000 Jewish men were arrested, simply for being Jewish. Most of the surviving Jewish prisoners were released on the condition they would leave the country.

World War II

World War II began on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded neighboring Poland. The war provided the opportunity and motivation for more extreme Nazi policies. Nazi “security” policies focused on potential leaders of Polish resistance. SS and police units arrested or killed tens of thousands of wealthy landowners, clergymen, and educated professionals (both ethnic Poles and Jews). German army units and “self-defense” forces composed of ethnic Germans living in Polish towns participated in executions of civilians.

Inside wartime Germany, the Nazis began a radical program to “strengthen the German race” by organizing the systematic killing of disabled Germans seen as a drain on national resources. In a secret note backdated to September 1, 1939, Hitler authorized designated physicians to provide a “mercy death” for “incurably ill” patients. Nazi leaders’ talk of “euthanasia” and “mercy death” hid the fact that the clandestine operation was a cynical program of mass murder. Its victims were transported from mental health facilities and other care institutions to special “euthanasia” centers equipped with gas chambers disguised as showers. The vast majority of those killed by gassing and later by lethal overdoses of medication between 1939 and 1945 were not Jews.

In occupied Poland, Nazi officials had a large Jewish population under their control. Almost 2 million of the 3.3 million prewar Jewish population of Poland lived in the German-occupied territories. (The Soviet Union had occupied eastern Poland in accordance with terms of the secret German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939.) Jews were victims of sporadic attacks in 1939 and 1940. However, Nazi policy at this time focused on segregating Jews from the majority ethnic Polish population and plundering Jewish property. This was achieved by forcing Jews to wear identifying Star of David cloth badges or armbands and to move into restricted areas called “ghettos.” The “ghettos” were under the control of German occupation forces and officials, assisted by local police. Ghettos also provided forced labor pools. Hundreds of thousands of ghettoized Jews died from starvation, disease, and other harsh conditions.

The ultimate fate of Polish Jews and Jews still living in Greater Germany remained to be decided. Nazi officials considered various plans for moving these “unwanted” people onto some kind of “reservation.” For example, Nazi officials started drawing up plans to transport Jews to the French island colony of Madagascar off the southeastern coast of Africa. The plan was later abandoned.

Systematic Mass Murder of Jews

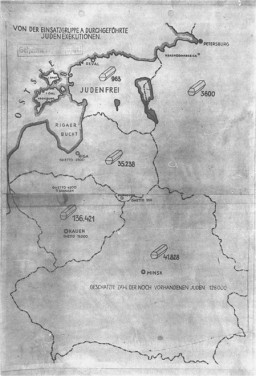

On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union in a planned “war of extermination” against communism and the linked “Judeo-Bolshevik” threat. Some four million Jews lived in territories under Soviet control. SS and police units behind the front lines began rounding up and shooting supposed “security” threats. At first the targets were mostly Jewish men of military age. Within weeks, however, the killing turned genocidal and included the murder of Jewish women and children and the destruction of whole Jewish communities. This escalation unfolded at different rates in different regions, depending on decisions of individual officers in the field as they responded to ideologically driven pressures and rewards from the Nazi leadership in Berlin. The Nazi units conducting the shooting operations received assistance from locals and militias composed of eastern Europeans.

In the fall of 1941, as mass murder of Jews in German-occupied territories in eastern Europe continued apace, Nazi leaders began planning the systematic, continent-wide genocide of all Europe’s Jews. One signal of the change in policy was the prohibition of Jews’ emigration from the European continent, beginning October 23, 1941. That month, German authorities began deporting thousands of German Jews "to the east," mostly to ghettos. After a meeting of senior German government officials convened in the Wannsee district of Berlin in late January 1942, “the final solution of the Jewish question” became formal state policy. The notes for the Wannsee meeting listed as “involved” in the “final solution” a total of 11 million Jews living in 34 countries and territories. By the time of the conference, 1.5 million Jews had been killed.

In 1942, a new method of killing Jews by poisonous gas was introduced, borrowed from the earlier “euthanasia” program. Nazis and local police began to empty the ghettos in violent liquidation operations. They transported more than a million Polish Jewish men, women, and children to killing centers (Chełmno, Belżec, Treblinka, and Sobibor) where, with very few exceptions, they were killed by gassing upon arrival.

Elsewhere in Europe, Nazi leaders and German diplomats requested that officials in German-conquered or German-allied countries hand over all Jewish men, women, and children for deportation “to the East.” Many countries cooperated, especially when Germany seemed invincible before the defeat of German forces at Stalingrad, USSR, in February 1943. Most of the Jews deported from western and southern European countries were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and killed in gas chambers soon after arrival. Some able-bodied adults were selected for slave labor, which often proved a temporary reprieve from death. In almost every case, local officials and police forces helped to carry out the deportations.

Even in spring and summer of 1944, with Soviet forces approaching, the Germans continued killing. Some 425,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau by the Germans and 14,000 Hungarian police. Three quarters of them were gassed upon arrival.

Toward the final days of the war, the Nazis evacuated prisoners from concentration and forced labor camps and moved them by transport and on foot toward camps in Germany’s interior. Thousands died from harsh conditions or were shot on route, showing Nazi zealousness to the end.

Critical Thinking Questions

What can we learn from the massive size and scope of the Holocaust?

How were various professions involved in preparing and carrying out the laws which implemented the whole process? What lessons can be considered for contemporary professionals?

Across Europe, the Nazis found countless willing helpers who collaborated or were complicit in their crimes. What motives and pressures led so many individuals to persecute, murder, or abandon their fellow human beings?

How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity?