How did postwar trials shape approaches to international justice?

The aftermath of the Holocaust raised questions about the search for justice in the wake of mass atrocity and genocide. The World War II Allied powers provided a major, highly public model for establishing international courts to penalize individuals for wartime crimes.

Explore this question to learn about how crimes were defined and tried in the postwar years, as well as how this groundwork influenced future approaches to international justice.

See related articles for background information related to this discussion.

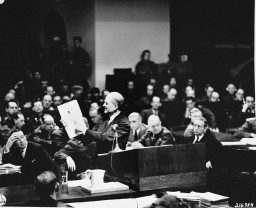

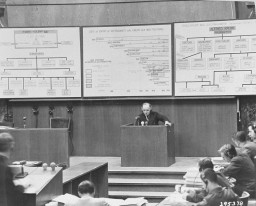

The World War II Allied Powers—Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States—provided a major model for the future when they created the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg. Between November 20, 1945, and October 1, 1946, the IMT tried 22 surviving former leaders of Nazi Germany. (Dictator Adolf Hitler and SS leader Heinrich Himmler had committed suicide at the end of the war.) It convicted 19 and acquitted 3. The Nuremberg Charter, signed by the Allies on August 8, 1945, set out three categories of crimes to be tried by the IMT:

- Crimes against peace, which included planning, preparing, initiating, and waging a war of aggression, as well as conspiring to commit any of those acts;

- War crimes, which included murder, ill-treatment, and deportation to slave labor of civilians, murder and ill-treatment of prisoners of war, and killing of hostages, as well as plunder and wanton destruction;

- Crimes against humanity, specified as murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, or inhumane treatment of civilians, and persecution on political, racial or religious grounds.

The Nuremberg Charter directed the IMT to conduct a fair trial and to grant defendants certain due process rights. These included the right to have legal counsel, to cross-examine witnesses, and to present evidence and witnesses. The IMT prosecutors charged the defendants on 4 counts, with the first count being conspiracy to commit war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace. Defendants were not allowed to escape responsibility for their crimes by claiming that they had followed superior orders or that they were exercising powers granted by international law to sovereign states.

In addition to the Nuremberg IMT, a US military tribunal in Nuremberg held twelve more trials of German leaders for the crimes defined in the Nuremberg Charter. Established in Tokyo in 1946, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East also tried Japanese leaders under rules of the Nuremberg Charter.

Criticism

Some critics called the trials “victors’ justice” because the Allies only tried their defeated enemies. The Allies did not subject their own actions to similar judgement. Critics also pointed out that the “due process” rights granted to the defendants were not as extensive as those given in civilian courts. Some also argued that the “crimes against peace” and “crimes against humanity” charges were unjust because the actions were not recognized as international crimes when they were committed.

The “crimes against humanity” charge came under particular criticism. Its definition implied that Axis leaders could be tried for actions their governments took against their own citizens. This violated the basic principle of international law, which does not regulate how a sovereign state treats its subjects.

Others have criticized the postwar tribunals for being too restrictive in their procedures and definitions of international crimes. Particularly faulted is the decision to consider crimes against humanity committed only in connection with the war. The IMT did not consider crimes against humanity that Germany committed solely against Germans or in the years before the war. Although the newly-coined term “genocide” was mentioned during the Nuremberg IMT, it was not one of the charges prosecuted. Nor were rape and sexual violence. Finally, the Nuremberg IMT prosecutors’ reliance primarily on German documents as evidence opened them to criticism that they excluded victims’ voices from the justice process.

UN Recognition of the Nuremberg Charter as Binding Law

In 1946, following the Nuremberg IMT verdicts, the United Nations (UN) unanimously recognized the judgment and the Nuremberg Charter as binding international law. The key “Nuremberg principles” recognized by the UN are:

- Crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity are offenses under international law;

- Any individual, even a government leader, who commits an international crime may be held legally accountable;

- Punishment for international crimes should be determined through a fair trial based upon the facts and the law;

- A perpetrator of an international crime who acted in obedience to orders from a superior still bears legal responsibility for the crime.

In addition to the Nuremberg Principles, the UN endorsed various conventions, treaties, and declarations during the early postwar period. It aimed to develop a system of international law that protects the peace and security of all humanity, and punishes acts that threaten them. In December 1948, the UN adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. In 1949, UN member states approved new Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Conventions replaced pre-World War II conventions that provided protections for combatants during international armed conflicts. In addition to broadening the earlier protections, the new conventions for the first time provided protections for civilians. They also established rules for domestic armed conflicts, such as civil wars.

Following the IMT trials, the UN sought to create a universal code of international crimes and a permanent international tribunal to try them. The tensions of the Cold War blocked these efforts for 50 years. During this time, international crimes continued to be committed on a massive scale.

Only in the 1990s did the UN agree to create special “Ad Hoc” international tribunals to try the perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide committed during ethnic conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. Unlike the Nuremberg IMT, the Yugoslavia and Rwanda tribunals were civil rather than military. They did not have prosecutors or judges from countries that had been involved in the conflicts. They handed down the first convictions for genocide and established that rape and sexual violence can be charged as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Additional conflicts have given rise to special “hybrid” courts that combine national and international law and personnel. In 2012, the Special Court for Sierra Leone confirmed a precedent set at Nuremberg. The precedent established that even heads of state can be convicted of international crimes. It found former Liberian president Charles Taylor guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Nuremberg’s Early Influence on International Law

Eichmann Trial: Photographs The trials before these tribunals set important precedents. Prior to them, international law and practice were limited to regulating relations between sovereign states. By creating two new crimes—“crimes against peace,” and “crimes against humanity”—the Nuremberg Charter established that international law should also protect individuals from state-sponsored aggression, murder, mistreatment, and persecution. In addition, the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials for crimes committed in a number of countries implied that prosecution for international crimes does not have to occur in courts in the states where the crimes occurred. Israel used this concept of universal jurisdiction to try Adolf Eichmann in a Jerusalem courtroom in 1961.

The war crimes trials of thousands of Axis perpetrators before domestic courts of countries in Europe, Asia, and the Pacific further strengthened the principle that individuals can be held accountable for wartime violence.

Rome Statute of 1998 Builds on Nuremberg Charter

In 1998, some of the UN member states adopted the Rome Statute. The Rome Statute codified the international crimes of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. It also created a permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) to try perpetrators. In addition to genocide, the Rome Statute added to the acts that the Nuremberg Charter defined as war crimes and crimes against humanity by including such acts as torture, sexual violence, and apartheid. The Rome Statute also established that crimes against humanity may be committed in peacetime as well as during armed conflict. Under the Rome Statute, defendants enjoy greater due process rights than the Nuremberg Charter provided. Victims are also permitted to present evidence in addition to evidence presented by prosecutors.

The ICC began operating in 2002. In 2010, the powers who signed the Rome Statute agreed upon the definition of the international crime of aggression. They added it to the ICC’s jurisdiction starting in 2018. Currently, 123 nations have ratified the Rome Statute and recognize the ICC’s jurisdiction. Among the states that have not adopted the Rome Statute are China, Russia, and the United States.

Today, perpetrators are facing justice before the ICC and several hybrid tribunals and domestic courts of a number of states. It is unlikely that these efforts to hold perpetrators accountable for international crimes would be occurring without the highly public model provided by the Nuremberg Charter and trials. As Nuremberg prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz has written, the Nuremberg trials planted “seeds of a future legal order based upon a humanitarian consideration of all people as fellow human beings, entitled to equal dignity and to peace.”

Nevertheless, international crimes continue to be committed throughout the world. Their perpetrators rarely face justice. Despite considerable progress in developing a system of international criminal law, the seeds planted at Nuremberg have yet to fully bear fruit.

Critical Thinking Questions

Is it ever too late to seek justice?

Besides military participants, what other professionals were charged with crimes in the wake of the Holocaust? Have other professionals been indicted in other genocide trials?

What are the advantages and drawbacks of international tribunals? Of national tribunals?

Can the legacy of a nation's past influence efforts to pursue justice after conflict and mass atrocity? Can national ambitions usurp the quest for justice?

Why is it important to document mass atrocity and genocide? What different types of sources have been used as evidence in trials?