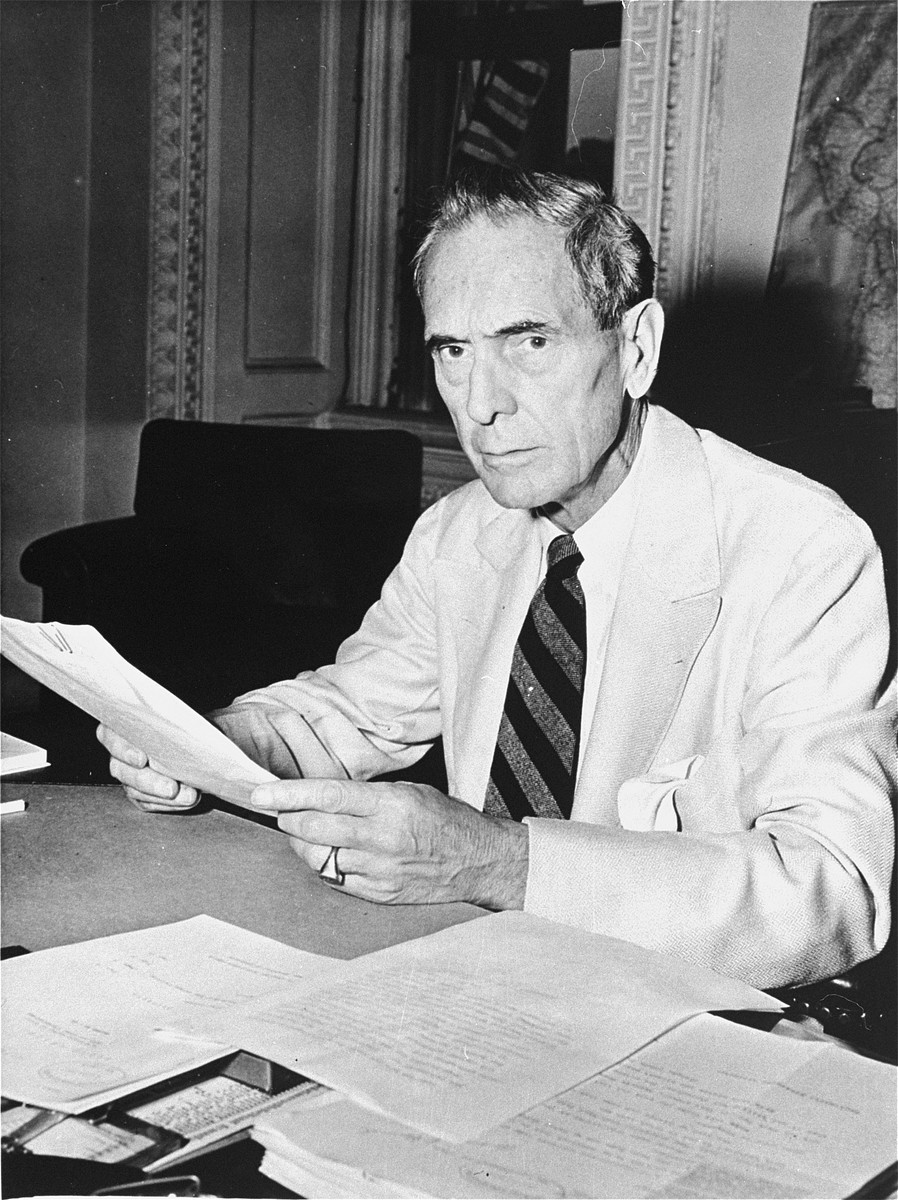

Breckinridge Long

Samuel Breckinridge Long was an Assistant Secretary in the US State Department during World War II, from 1940–1944. Many of the policies implemented by the State Department’s Visa Division, which Long supervised, slowed immigration to the United States for the hundreds of thousands of refugees attempting to escape persecution and murder by Nazi Germany.

Key Facts

-

1

Between 1939 and 1942, Breckinridge Long implemented new State Department policies which prioritized US national security over humanitarian concerns.

-

2

In November 1943, Long testified to a Congressional committee about the State Department’s work on behalf of refugees. Details of his testimony were quickly proven false, and in January 1944, he was removed from his position overseeing the Visa Division.

-

3

Breckinridge Long was often accused, both during his time at the State Department and in the years since the Holocaust, of being personally antisemitic and unsympathetic to European refugees, especially Jews fleeing Nazi persecution.

Introduction

Samuel Breckinridge Long was born in 1881 in St. Louis, Missouri, to a wealthy family. He graduated from Princeton University in 1904, studied at the Washington University School of Law, and received a Master’s degree from Princeton in 1909.

Long practiced law in Missouri until 1917 when President Woodrow Wilson appointed him Third Assistant Secretary in the State Department. Long ran for the US Senate twice, in 1920 and 1922, losing both elections. He supported the 1933 presidential candidacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt (whom he knew from the Wilson administration) and served as American ambassador to Benito Mussolini’s Italy from 1933 to 1936.

When World War II began in September 1939, President Roosevelt asked Long to return to the State Department. He became an Assistant Secretary of State in January 1940, serving in that position until his resignation in November 1944.

The Visa Division

As part of his duties at the US State Department, Breckinridge Long supervised the Visa Division. This division oversaw the issuing of American immigration and transit visas at consulates overseas. After the outbreak of war, in September 1939, Long reentered the State Department.

At the time, increased panic after the Anschluss in March 1938 and Kristallnacht in November 1938 led more than 300,000 people born in Germany—mostly Jews—to add their names to the waiting list for an American immigration visa. The German quota allowed a maximum of 27,370 people born in Germany to immigrate to the United States each year. This meant that the waiting list was more than ten-years long. The US immigration quota from Germany was filled for the first time in 1939, and almost filled in 1940. In all other years of Nazi rule (1933–1945) the quota was not filled.

National Security Concerns

After the German invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium, and France in May 1940, most Americans feared that Nazi spies or saboteurs might be trying to enter the United States by posing as immigrants.

In late June 1940, ten days after France’s surrender to the Nazis, Long wrote a memo to other State Department officials envisioning the ways in which they might stop all immigration in case of a national emergency. He wrote that consular officers could “put every obstacle in the way and require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative advices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas.”

Long’s memo was never put into effect to halt all immigration. Very soon after he wrote it, however, Secretary of State Cordell Hull instructed all State Department officials abroad to take additional caution in screening refugees. If these officials had any doubt about the identity or intentions of the refugee, they were told to refuse to grant the immigration visa.

Long also expressed concerns about the work of the President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees. This non-governmental organization collected the names of prominent religious and intellectual leaders in danger and submitted them to the State Department to streamline the visa process on their behalf. Long complained that the advisory committee submitted hundreds of names with little additional information. He worried that some of the refugees were communists, were not legitimately in danger, or would be security threats. He convinced President Roosevelt to limit the number of names the advisory committee could submit, and reiterated to consular officials their power to deny visas, even for recommended individuals.

In June 1941, Long’s Visa Division instructed consular officials in Europe to deny visas to any applicant with close relatives still living in Nazi-occupied territory.

In July 1941, the State Department announced that all visa applications needed to be reviewed in Washington, DC, by an interdepartmental visa review committee, made up of the State and Justice Departments, military intelligence, and FBI personnel. This new regulation, which, as Long wrote “will consider the cases of visa applicants from the viewpoint of national defense,” lengthened the already long and difficult immigration process .

Rescue Resolution

In early 1943, more information about the Nazi plan to murder European Jews became available in US newspapers and magazines. Breckinridge Long attempted to dispel public pressure to take specific rescue action on behalf of European Jews. He chose the American delegates to the April 1943 Bermuda Conference, issuing instructions which effectively ensured that negotiations with the British government over rescue and relief possibilities would not lead to any significant new actions on behalf of Europe’s Jews.

Long also briefly attempted to stop intelligence about mass murder from reaching the United States, because he feared that the release of such news might result in additional pressure on the State Department.

In November 1943, the US House of Representatives’ Committee on Foreign Affairs held hearings on a bipartisan resolution that called on President Roosevelt to appoint a commission to create and implement plans to rescue European Jews. Long monitored these committee hearings closely, and himself testified in a closed session, describing the State Department’s work to assist refugees and provide humanitarian relief. The Congressmen were impressed, and Long decided to publish his testimony for the public.

Almost immediately, Long’s claim that the United States had accepted 580,000 refugees since 1933, was proven false. (The actual number, which varies depending on the definition of “refugee,” was much lower—certainly far less than half the number of 580,000 that Long provided to Congress.) Long's misleading testimony was widely criticized by Congressmen and others. In January 1944, as US Treasury Department discovered his efforts to suppress information about the Holocaust, he was reassigned as part of a State Department reorganization.

In November 1944, Breckinridge Long resigned from the State Department.

Conclusion

During the 1930s and 1940s, the State Department tolerated nativist, xenophobic, and often antisemitic attitudes and actions. Breckinridge Long was often accused, both during his time at the State Department and in the years since the Holocaust, of being personally antisemitic and unsympathetic to European refugees, especially Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. Under his supervision, the Visa Division placed new restrictions on immigration due to national security concerns, even though it was clear that Jewish refugees in Europe were in serious danger.

During the war, Long’s attempts to prevent public pressure for action backfired, and the State Department (and Long personally) was blamed for inaction. Today, he remains one of the more controversial figures for those who study Americans’ response to the Holocaust.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Breckinridge Long, Letter to Robert Jackson, 1941 June 4. RG-59, CDF, 40-44, 811.111/W.R/416; NACP.

Critical Thinking Questions

What were the principal reasons for US resistance to immigration in 1924? Did these factors change during the Holocaust? Are they influential currently?

What pressures and motivations drive support or resistance to immigration, or even refugee rescue, in your country?

How do politicians and citizens prioritize problems on the home front and endangered populations in other countries?