Jasenovac

The Jasenovac camp complex consisted of five detention facilities established between August 1941 and February 1942 by the authorities of the so-called Independent State of Croatia. As Germany and its Axis allies invaded and dismembered Yugoslavia in April 1941, the Germans and the Italians endorsed the proclamation of the so-called Independent State of Croatia by the fanatically nationalist, fascist, separatist, and terrorist Ustaša organization on April 10, 1941.

After seizing power, the Ustaša authorities erected numerous concentration camps in Croatia between 1941 and 1945. These camps were used to isolate and murder Jews, Serbs, Roma (also known as Gypsies), and other non-Catholic minorities, as well as Croatian political and religious opponents of the regime. The largest of these centers was the Jasenovac complex, a string of five camps on the bank of the Sava River, about 60 miles south of Zagreb. It is presently estimated that the Ustaša regime murdered between 77,000 and 99,000 people in Jasenovac between 1941 and 1945.

In late August 1941, the Croat authorities established the first two camps of the Jasenovac complex—Krapje and Brocica. These two camps were closed four months later. The other three camps in the complex were: Ciglana, established in November 1941 and dismantled in April 1945; Kozara, established in February 1942 and dismantled in April 1945; and Stara Gradiška, which had been an independent holding center for political prisoners since the summer of 1941 and was converted into a concentration camp for women in the winter of 1942.

The camps were guarded by Croatian political police and personnel of the Ustasa militia, which was the paramilitary organization of the Ustaša movement.

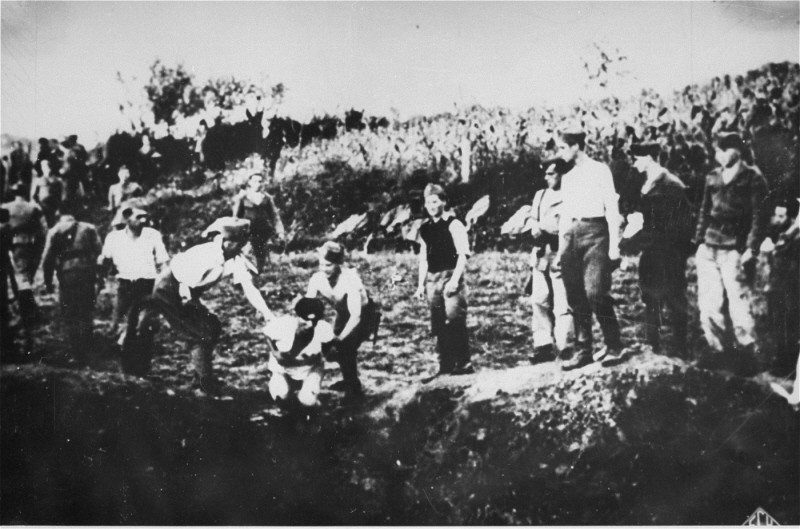

Conditions in the Jasenovac camps were horrendous. Prisoners received minimal food. Shelter and sanitary facilities were totally inadequate. Worse still, the guards cruelly tortured, terrorized, and murdered prisoners at will.

Between its establishment in 1941 and its evacuation in April 1945, Croat authorities murdered thousands of people at Jasenovac. Among the victims were:

- between 45,000 and 52,000 Serb residents of the so-called Independent State of Croatia

- between 12,000 and 20,000 Jews

- between 15,000 and 20,000 Roma (Gypsies)

- between 5,000 and 12,000 ethnic Croats and Muslims, who were political opponents of the regime

The Croat authorities murdered between 320,000 and 340,000 ethnic Serb residents of Croatia and Bosnia during the period of Ustaša rule; more than 30,000 Croatian Jews were killed either in Croatia or at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Between 1941 and 1943, Croat authorities deported Jews from throughout the so-called Independent State to Jasenovac and shot many of them at the nearby killing sites of Granik and Gradina. The camp complex management spared those Jews who possessed special skills or training, such as physicians, electricians, carpenters, and tailors. In two deportation operations, in August 1942 and in May 1943, Croat authorities permitted the Germans to transfer most of Croatia's surviving Jews (about 7,000 in total), including most of those still alive in Jasenovac, to Auschwitz-Birkenau in German-occupied Poland.

As the Partisan Resistance Movement under the command of Communist leader Josip Tito approached Jasenovac in late April 1945, several hundred prisoners rose against the camp guards. Many of the prisoners were killed. A few managed to escape. The guards murdered most of the surviving prisoners before dismantling the last three Jasenovac camps in late April. The Partisans overran Jasenovac in early May 1945.

Number of Victims

Determining the number of victims for Yugoslavia, for Croatia, and for Jasenovac is highly problematic, due to the destruction of many relevant documents, the long-term inaccessibility to independent scholars of those documents that survived, and the ideological agendas of postwar partisan scholarship and journalism, which has been and remains influenced by ethnic tension, religious prejudice, and ideological conflict. The estimates offered here are based on the work of several historians who have used census records as well as whatever documentation was available in German, Croat, and other archives in the former Yugoslavia and elsewhere.

As more documents become accessible and more research is conducted into the records of the Ustaša regime, historians and demographers may be able to determine more precise figures than are now available.