Escape from German-Occupied Europe

Leaving German-occupied Europe became more and more difficult after the start of World War II and almost impossible as the war progressed.

Key Facts

-

1

The possibility of rescue varied from country to country, depending on relations with Germany, previous levels of antisemitism, the course of the war, and many other factors.

-

2

Few countries were willing to accept Jewish refugees, but some individuals and organizations were able to save thousands.

-

3

Most non-Jews neither aided nor hindered the "Final Solution," and relatively few people helped Jews escape.

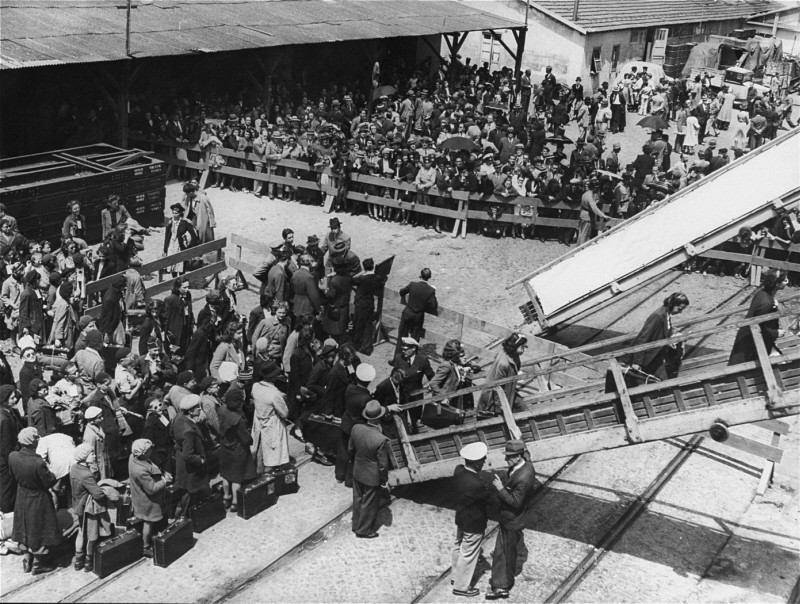

Even before the beginning of World War II, many Jews sought to escape from countries under Nazi control. Between 1933 and 1939, more than 90,000 German and Austrian Jews fled to neighboring countries (France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Czechoslovakia, and Switzerland). After the war began on September 1, 1939, escape became much more difficult. Nazi Germany technically permitted emigration from the Reich until November 1941. However, there were few countries willing to accept Jewish refugees and wartime conditions hindered those trying to escape. In 1941–42, with the beginning of systematic shooting of Jews in the Soviet Union and the deportation of European Jews to killing centers, escape literally became a matter of life and death.

Most non-Jews neither aided nor hindered the "Final Solution" and relatively few people helped Jews escape. Among those who helped Jews were various local and international Jewish organizations, such as the Joint Distribution Committee, the Jewish Agency for Palestine, and the World Jewish Congress. In addition, sympathetic non-Jews, motivated by opposition to Nazism, by moral and religious principles, or by human compassion, provided assistance to Jews at sometimes tremendous personal risk.

Escape to Soviet-Occupied Poland and the Interior of the Soviet Union

Between 1939 and 1941 nearly 300,000 Polish Jews, almost 10 percent of the Polish Jewish population, fled German-occupied areas of Poland and crossed into the Soviet zone. While Soviet authorities deported tens of thousands of Jews to Siberia, central Asia, and other remote areas in the interior of the Soviet Union, most of them managed to survive. After the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, more than a million Soviet Jews fled eastward into the Asian parts of the country, escaping almost certain death. Despite the harsh conditions of the Soviet interior, those who escaped there constituted the largest group of European Jews to survive the Nazi onslaught.

Escape to Neutral Countries

Close to 30,000 Jews were admitted into Switzerland, although an estimated 20,000 were turned away at the Swiss border. Spain allowed almost 30,000 Jewish refugees to enter, primarily from 1939 to 1941. These refugees, mostly from France, were permitted to cross Spain on their way to Portugal. German pressure reduced the number of Jews admitted entry into Spain to fewer than 7,500 during the years 1942–44, although Spanish consuls distributed 4,000-5,000 identity documents (crucial to escape) to Jews in various parts of Europe. Portugal (a neutral country friendly to the Allies) permitted many thousands of Jews to reach the port of Lisbon. A number of American and French Jewish organizations helped the refugees, once in Lisbon, to reach the United States and South America.

Neutral Sweden provided sanctuary for some Norwegian Jews in 1940 and for virtually the entire Danish Jewish community in October 1943. The Danish resistance movement organized the escape of 7,000 Danish Jews and 700 of their non-Jewish relatives across the Sund Channel from Denmark to Malmo, Sweden.

Escape via the Balkans to Palestine

From 1937 to 1944, the Zionist movement organized the escape of 18,000 central and east European Jews to Palestine. At first Greek harbors were used to embark on the voyage to Palestinian ports. Later, Jewish refugees left via Black Sea ports in Bulgaria and Romania. Many of the boats needed to refuel in Turkish ports. Despite Turkey's efforts to prevent these ships from docking, more than 16,000 Jews passed through Turkey en route to Palestine. In a tragic incident, the Struma, a ship carrying refugees bound for Palestine, was sunk off the Turkish coast. Although the cause of the sinking is not definitively known, it is assumed that the "Struma" was mistakenly torpedoed by a Soviet submarine.

Escape to Italian-Occupied Areas

Italian forces protected Jews in the Italian occupation zones in Yugoslavia, France, and Greece. From mid-1942 to September 1943, Italy gave aid to Jews in several areas under its occupation. These included Dalmatia and Croatia, where 5,000 Jews found refuge; southern France, where at least 25,000 Jews fled; and Greece, where 13,000 Jewish refugees found temporary shelter. Despite unceasing demands and protests from the Germans, Croatian fascists, and the Vichy police, the Italian authorities refused to hand over these Jews. The Italians also extended protection to Jews in Tunisia.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Why did some countries allow Jewish refugees to enter and others did not?

- Investigate the difficulties and challenges Jewish refugees faced in looking for refuge outside German-occupied Europe.

- What responsibilities do other nations have regarding refugees from oppressive regimes?