German and Austrian Jewish Refugees in Shanghai

Shanghai before World War II

In the years preceding World War II, Shanghai was a divided city. In 1842, when the then-minor port was opened to western trade, Great Britain, the United States, France, Italy, and Portugal established extraterritorial rights in the city's so-called foreign concessions-the International Settlement, administered by a municipal council of western powers, and the French Concession, headed by the French consul general.

Before the arrival of Jews fleeing Nazi persecution and the war in Europe, the International Settlement and French Concession were home to two main Jewish groups. The older and smaller group consisted of about 700 Sephardic Jews whose fathers and grandfathers had arrived from Iraq as traders in the mid-1800s and quickly ascended the social and economic ladder. The second and larger community comprised a few thousand Ashkenazi Jews who had fled to China as refugees from Russia during the Revolution of 1917. Most of them earned modest livings as small business owners.

In the aftermath of 1937 Sino-Japanese fighting, large sections of Shanghai fell under Japanese control, including the part of the International Settlement referred to as Hongkew.

Arrival of German and Austrian Jews

An estimated 17,000 German and Austrian Jews first trickled into Shanghai after the beginning of Nazi persecution of Jews in 1933 and then, following the 1938 violence of Kristallnacht, streamed in like a flood. These early refugees usually immigrated to Shanghai as families. Stripped of most of their assets before fleeing the Reich, these thousands of refugees swarmed into Hongkew because they could not afford to live anywhere else in the foreign concessions.

During the 1930s, Nazi policy encouraged Jewish emigration from Germany, and a ship's passage enabled a person to gain release, even from a concentration camp. At first, Shanghai seemed an unlikely refuge, but as it became clear that most countries in the world were limiting or denying entry to Jews, it became the only available choice. Until August 1939, no visas were required for entering Shanghai. Ernest Heppner, who fled Breslau with his mother in 1939, recalled that the

“main thing was to get out of Germany, and really at this point, people did not care where we went, anywhere just to get away from Germany” (Ernest Heppner, USHMM Oral History, 1999).

Arrival in Shanghai was a shock, especially for those who had just stepped off a European liner on which they had been served breakfast by uniformed stewards and now found themselves lining up for lunch in a soup kitchen. Once the refugees settled in, finding work was a challenge, and many refugees had to rely on at least some charitable relief.

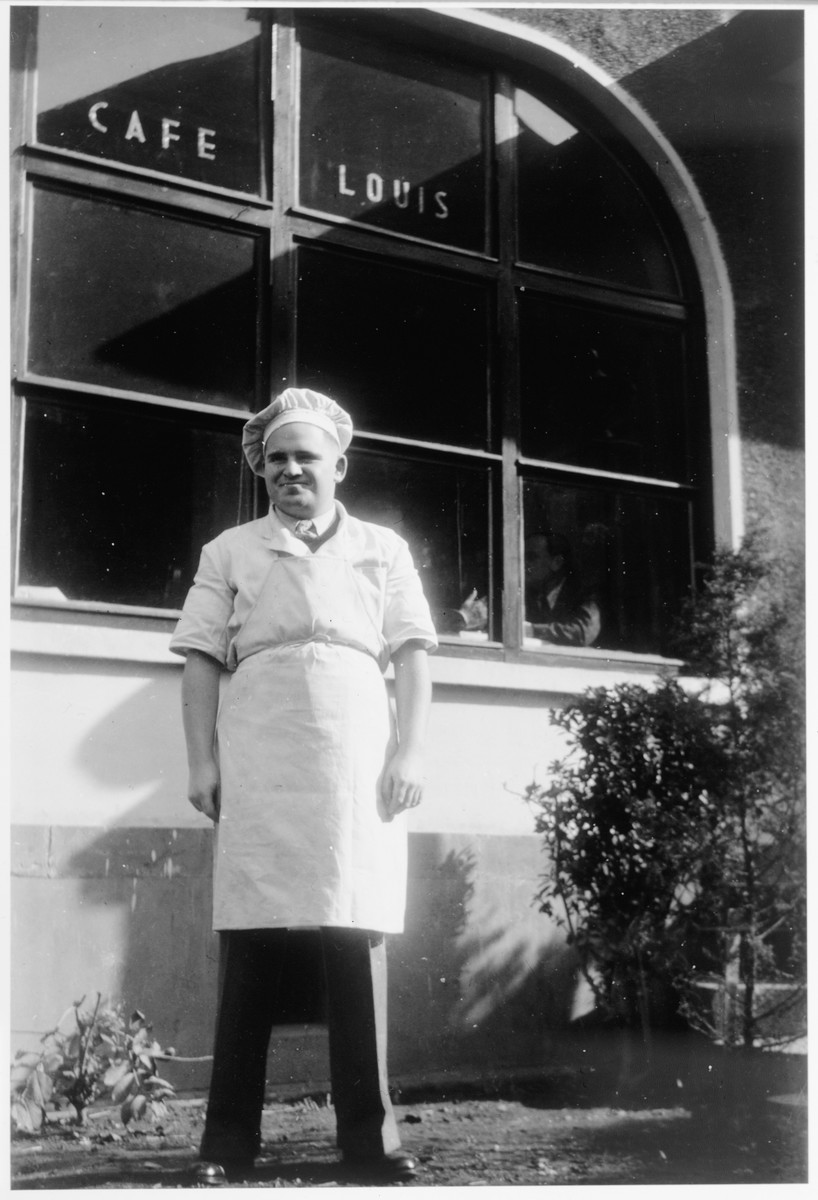

Still, the majority of German and Austrian Jews managed. Despite the blows to Shanghai's economy dealt by the Sino-Japanese conflict, some of them adapted well, taking advantage of opportunities that the city offered. The Eisfelder family, who arrived at the end of 1938, opened and operated Café Louis, a popular gathering place for refugees throughout the war years. Others established small factories or cottage industries, set themselves up as doctors or teachers, or worked as architects or builders to transform sections of bombed-out Hongkew. By 1940, an area around Chusan Road was known as “Little Vienna,” owing to its European-style cafés, delicatessens, nightclubs, shops, and bakeries.

When Shanghai's refugee population suddenly jumped from about 1,500 at the end of 1938 to nearly 17,000 one year later, the local Jews were overwhelmed and hard pressed to find the resources to help needy families. The Committee for Assistance of European Jewish Refugees in Shanghai, formed in 1938 by prominent local Jews, turned to the Joint Distribution Committee in New York for additional funds. The JDC appropriation rose from $5,000 in 1938 to $100,000 in 1939. Even this barely kept up with the mounting demands. By late 1939, more than half of the refugee population required financial help for food or housing.

The Committee for Assistance established five group shelters for a minority of totally impoverished German and Austrian Jews. These shelters were called Heime (“homes” in German). The Ward Road Heim that opened in January 1939 was hastily converted from a former barracks and outfitted with hard, narrow bunk beds under which the residents stored their few belongings. By the end of 1939, about 2,500 people lived in the Heime, sleeping anywhere from six to 150 to a room. An additional 4,500 individuals ate in soup kitchens set up in the Heime but lived elsewhere in rented rooms. Many of them received relief help to pay for all or part of their housing costs.

Critical Thinking Questions

How and why did Shanghai become a refuge for European Jews?

What pressures and motivations spurred European Jews to take advantage of this drastic opportunity?