The Nazification of the German Police, 1933–1939

Beginning in 1933, the Nazis took control of and subsequently transformed the police forces of the Weimar Republic into instruments of state repression and, eventually, of genocide. They did so by Nazifying policing. The new government removed anti-Nazi police leaders, reorganized Germany’s police forces, and reoriented police culture towards Nazism.

Key Facts

-

1

Nazification changed the organizational structure, leadership, training, and values of Germany’s police forces.

-

2

The Nazis expanded police power and used the police to target people they considered their political, racial, social, and criminal opponents.

-

3

Although the new Nazi government fired or retired many police leaders, the vast majority of German policemen kept their jobs and served the Nazi state.

After Adolf Hitler became chancellor on January 30, 1933, he worked to turn Germany into a dictatorship under his sole control. To do so, the new government reoriented Weimar Germany’s previously democratic organizations and institutions to serve Nazi ideals. This meant eliminating constitutional rights and protections for individuals. It also meant inserting Nazi ideology into all aspects of life. This process is known as Nazification.

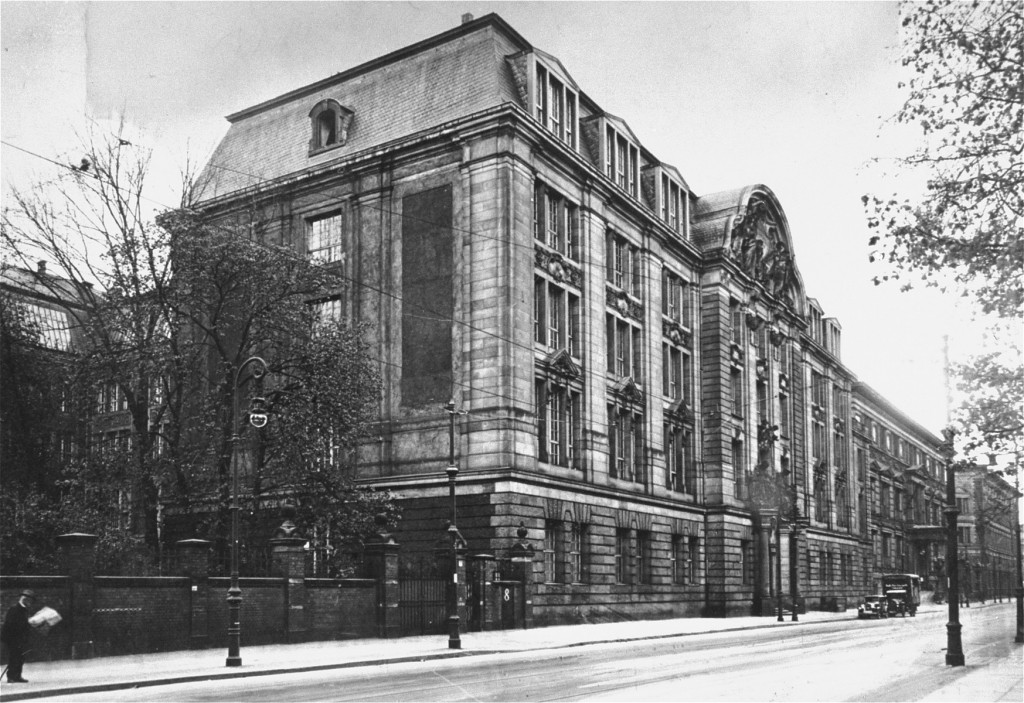

The Nazis believed that the police would have a particularly important role to play in the new Germany. Therefore, almost immediately after Hitler’s appointment, the Nazis sought to take over and transform Germany’s police forces. But the decentralized nature of German policing in 1933 made this difficult. At that time, various state and city governments—not the German chancellor—oversaw the country’s police forces. Nazification of the police could not happen overnight. In fact, it took several years. It was not until 1936 that the Nazis fully centralized all police forces under SS leader Heinrich Himmler’s control.

Expanding Police Power

In early 1933, the Nazis used a variety of measures to free the police from the constraints of the Weimar constitution. They simultaneously encouraged the police to target Nazism’s political opponents, namely Social Democrats and Communists. On February 17, 1933, Nazi Hermann Göring issued a decree to Prussian policemen instructing them to work with Nazi paramilitary organizations and to treat political enemies ruthlessly. The decree clearly stated that policemen would not be punished for shooting a Communist, and, in fact, they might even be disciplined for failing to do so.

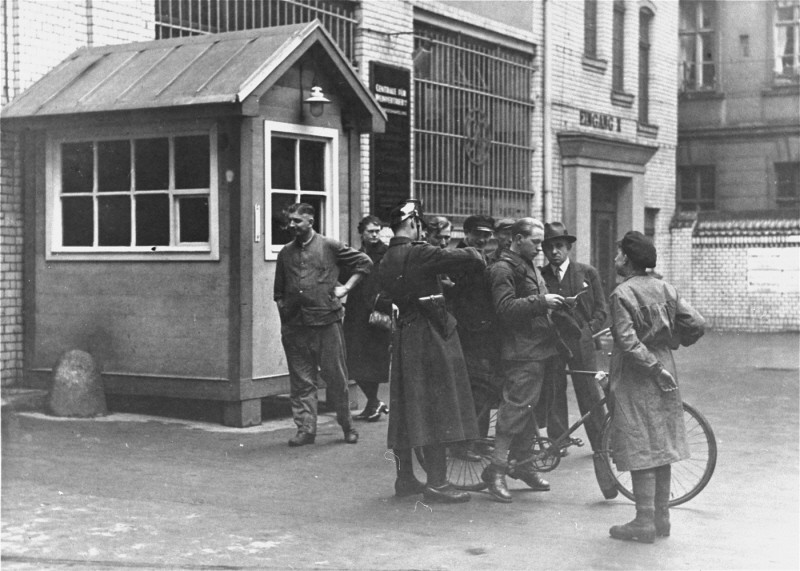

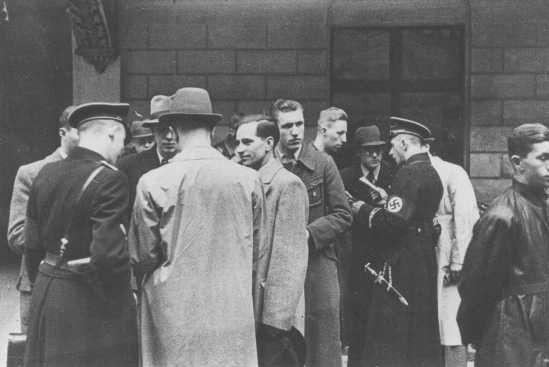

A few days later, on February 22, the Nazis began deputizing members of the SS, SA, and Stahlhelm (a nationalist veterans’ organization) as auxiliary policemen (Hilfspolizei) in many German states. In Prussia alone, 50,000 armed paramilitary men patrolled alongside policemen. These auxiliaries brutally arrested and beat political opponents, interning many of them in makeshift concentration camps. Typically, auxiliary policemen wore their paramilitary uniforms with a white armband.

The most important step in the process of Nazifying the police came after February 27, 1933, when an arson attack destroyed the German Reichstag (parliament building) in Berlin. Hitler responded with the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended civil rights and most legal protections in Germany. It also expanded the power of the police. This decree, which remained in force until the downfall of the Nazi regime, laid the foundation for Germany to become a police state.

Creating Loyal Policemen

In addition to expanding the powers of the police, the Nazis also wanted to guarantee that loyal—meaning Nazi—policemen controlled and filled Germany’s police institutions. This would make it easier for the Nazis to use the police forces for their ideological and dictatorial goals. The Nazis did not simply abolish the police or replace them all with Nazis. They needed existing police experience, knowledge, skill, and expertise.

Police leadership positions were politically appointed. This meant that whoever controlled the state and local governments could appoint the police chiefs. As the Nazis gained control of state and local government positions, they immediately appointed Nazi Party loyalists, often SA men, to police leadership positions.

The same men who had been terrorizing the police and the public just months before were now in charge of major police departments across Germany. For instance, prominent Berlin SA leader Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorff had stood trial in 1931–1932 after coordinating an antisemitic attack. Under Helldorff’s leadership, SA men had yelled antisemitic insults and attacked people they identified as Jews on Berlin’s main shopping thoroughfare. But in 1933, Helldorff was appointed Police President of Potsdam and, in 1935, of Berlin. This placed him in charge of the very same police force he had previously harassed.

Lower-level German policemen were civil servants, which came with certain job protections. Thus, to achieve their goals, the Nazis needed a legal reason to fire them or force them to retire. A new Nazi law adopted on April 7, 1933, did just that. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service gave the government the power to remove Jews and political opponents from the civil service. This included policemen. In Cologne, for example, thirty-one police officers (out of approximately 2,600) were removed under the law, mostly for political activity. Nonetheless, this purge of the police was relatively minor.

While most German policemen did not lose their jobs, this did not mean that nothing changed within Germany’s police forces. The Nazis used other personnel measures, namely reorganization and personnel transfers, to create Nazified police organizations. Nazi policemen were promoted or transferred to prominent positions, while politically unreliable policemen were given administrative duty or other less influential roles. Furthermore, top Nazi police officials worked to permanently recruit Nazis (especially SA men) into the police.

Most policemen adjusted quickly to the new regime.

Nazifying Police Culture

In the 1930s, Nazi police leaders remade police culture to align with Nazi values. This was part of their plan to create a National Socialist form of policing. Propaganda efforts tried to improve the public image of the police. Beginning in 1934, celebrations called “The Day of the German Police” honored the connection between the police and the people with parades and speeches. During those events, which eventually expanded to a full week, German policemen stood on street corners and collected money for the Nazi charity program Winter Relief (Winterhilfswerk). Propaganda depicted German policemen directing traffic, returning lost children, shaking hands with people, and teaching children new skills.

Nazi ideology became central to police training and police practice. In police newspapers and booklets, Himmler and other Nazi police leaders contrasted the new National Socialist police ideal with the Weimar-era police, whom the Nazis condemned as servants of a weak constitutional state. The new Nazi police were supposedly the “friend and helper” of the German people. Importantly, in Nazi Germany “the German people” did not mean German citizens or residents of Germany; instead, it meant “Aryan” Germans. Police were to act in ways that protected Aryans and served the entire racial community. This changed how policemen were supposed to identify potential threats, criminals, and enemies. No longer were they simply on the lookout for people who violated the law. Under the Nazi state, police were obligated to prevent perceived biological and racial threats as well.

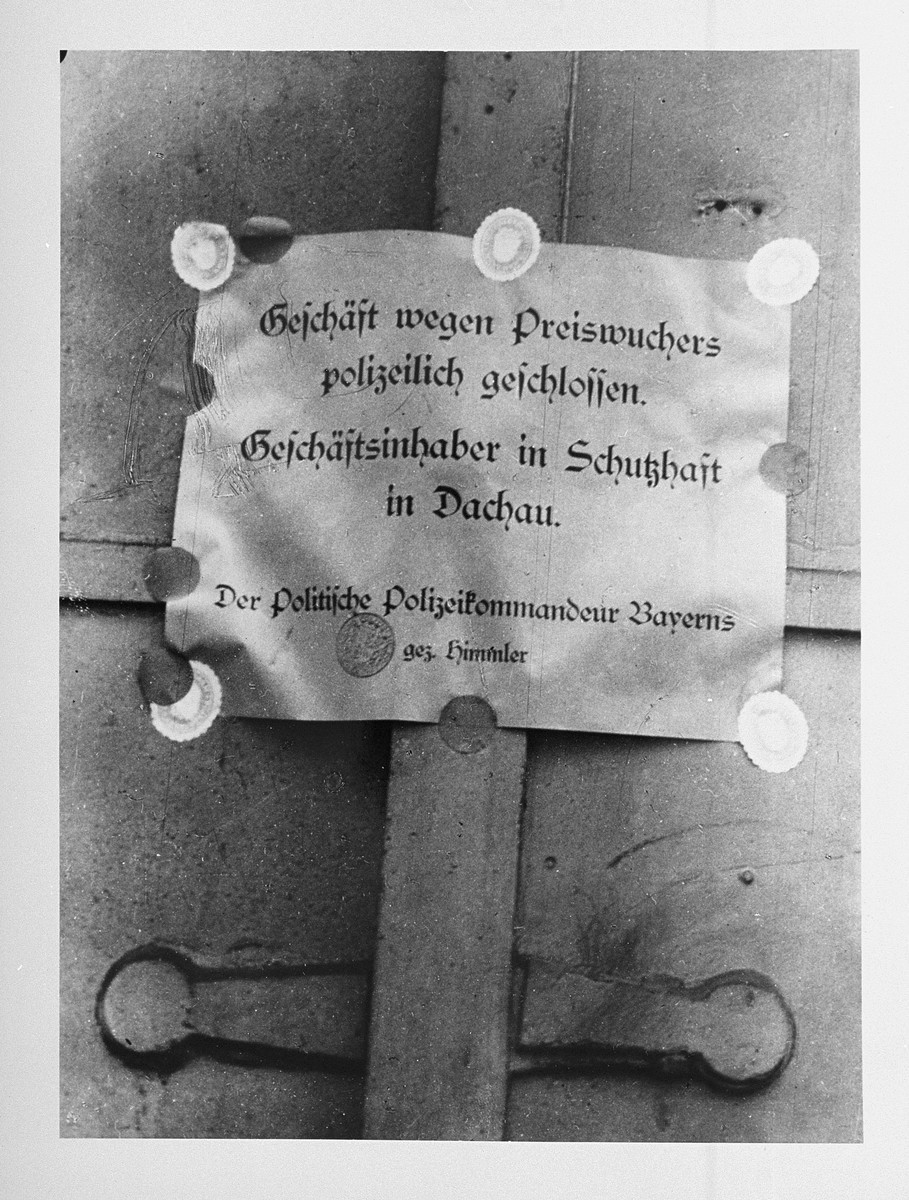

The Nazi police were also supposed to be incredibly harsh with Nazism’s political, racial, social, and criminal enemies. Many of these harsher tasks fell to the Kripo (Kriminalpolizei, criminal police) and Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei, secret state police), two police agencies with enormous power to arrest, incarcerate, and abuse people. In the 1930s, Nazism’s enemies included political opponents, people who they identified as professional criminals or asocials, and Jews.

Persecuting Germany’s Jews

Policemen supported the regime’s anti-Jewish policies. Members of the Order Police often ignored SA violence against Jews and vandalism of Jewish-owned property, especially when the violence was regime-sanctioned. They enforced antisemitic legislation and therefore helped isolate and persecute Jewish Germans. In the summer of 1938, Berlin Police President Helldorff and Joseph Goebbels, Gauleiter of Berlin and Minister of Propaganda, instructed the Berlin police force to use existing traffic regulations and other minor laws to harass the city’s Jews. After Kristallnacht in November 1938, German policemen arrested approximately 30,000 Jewish men and sent some 26,000 of them to concentration camps.

The behavior of German police forces in the 1930s eventually made it clear to most German Jews that they could not rely on the police to protect them or their property.

The invasion of Poland and the start of World War II on September 1, 1939, further radicalized Nazi policing. In the years that followed, policemen perpetrated horrific crimes, including the mass murder of Europe’s Jews.

Critical Thinking Questions

How did the role of law enforcement change during 1933-1945? Why?

What pressures and motivations may have influenced the choices of individual policemen?

Is a change in the role of law enforcement ever a possible warning sign for mass atrocity? What type of change could be problematic?

How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?