The Police in the Weimar Republic

In 1918, Germany transitioned from a semi-authoritarian empire to the Weimar Republic, a democracy that protected individual rights and limited police power. During the Weimar Republic, police struggled to respond to a rise in crime, political violence, and high unemployment. The Nazis promised to fix these problems, which helped policemen to eventually accept the new Nazi regime in 1933.

Key Facts

-

1

The creation of the democratic Weimar Republic (1918-1933) changed the political context in which German police forces operated.

-

2

Beginning in 1929, the Great Depression created new economic and political circumstances that made it difficult for police to maintain public order and solve crimes.

-

3

Most German policemen were not members of the Nazi Party prior to 1933.

In 1918, Germany’s defeat in World War I caused the collapse of the German Empire, known as the Kaiserreich. It also helped inspire a revolution. The new German government was called the Weimar Republic. It was a parliamentary democracy. This meant that the constitution guaranteed equality before the law. It ensured such civil liberties as freedom of speech, press, religion, and assembly. It also enacted universal suffrage: adult citizens, men and women, had the right to vote. In the new government, political parties played a much bigger role than they had ever played before.

Policing as a Political Issue

Policing became an important political issue in the Weimar Republic. Political parties competed for influence over Germany’s police forces. The political parties that supported the Weimar Republic and parliamentary democracy wanted to remake the police forces as democratic institutions. But right-wing nationalistic parties that rejected democracy sought a militarized police force. They wanted the police to defend Germany from left-wing revolutionaries, especially the country’s new Communist Party.

Germany’s police forces were decentralized at this time. The police were thus subordinate to state and city governments. As a result, political conflicts over policing varied across the country.

One of the best examples of how politics influenced policing is the case of Prussia. Prussia played an important role in Germany’s political landscape, including in the area of policing. Home to the capital city of Berlin, Prussia was Germany’s largest and most populous state. It made up more than 60 percent of Germany’s territory and population. There were 85,000 officials in the Prussian police forces. This accounted for more than 50 percent of all of Germany’s policemen.

Before the 1918 revolution, Prussia had been known for its authoritarianism. There were limited political freedoms in the state. But during the Weimar Republic, Prussia was a stronghold of democracy. A political coalition led by the Social Democratic Party controlled the Prussian state government. Thus, it also controlled the state’s police forces.

The Social Democratic Party was moderate, pro-democracy, and leftist. The party was popular with Germany’s industrial working class. Social Democratic police chiefs tried to change the police from enforcers of authoritarianism into servants of the people. They modernized police technology and improved training. Public relations campaigns and events were used to help improve the image of the police.

Policing a New Democracy, 1918-1923

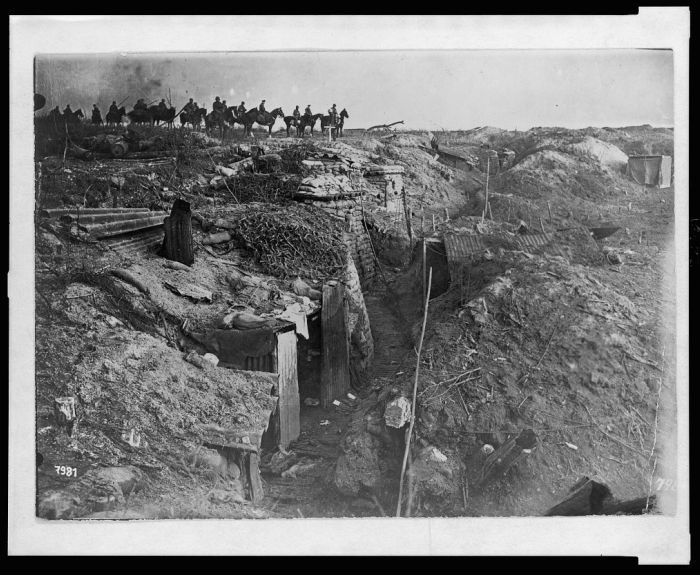

The earliest years of the Weimar Republic were chaotic. German soldiers returned home from World War I with guns and a new experience of violence. Wartime deprivation and postwar economic policies caused economic distress. This drove many people to begging, looting, theft, and rioting. Citizens demanded better living and working conditions. Strikes and demonstrations became common across Germany. Policemen also suffered dire economic conditions.

New political movements attempted to channel public grievances. Radical left- and right-wing movements inspired crowds to gather in the streets. Some of these political groups attempted to use violence to overthrow the government and seize power. It was the responsibility of the police to protect the government. The police were meant to stop the public disorder and arrest criminals. However, this was a situation they could not handle. The government chose to rely on other presences instead. It looked to the German military and right-wing paramilitaries. The latter were non-state organizations with members in uniforms and with weapons.

Policing during the “Golden Years,” 1924-1929

By 1924, the economy stabilized and political unrest largely subsided. Crime also began to decline. This era was known as the “Golden Years” of Weimar. Germany saw a cultural and commercial explosion, especially in Berlin.

The police continued to face unaccustomed challenges, however. In the German Empire, the right of citizens to assemble and demonstrate had been limited. Censorship had also protected the police from public criticism. But in the Weimar Republic, citizens could demonstrate and speak much more freely. By law, the police could not stop them from publicly expressing their opinions. Political parties took advantage of these changes. They staged regular marches and rallies. Even when these events were peaceful, they required a significant police presence for crowd control.

The Years of Crisis, 1930-1933

Beginning in late 1929, the Great Depression brought economic prosperity and political stability to a crashing end. The government ceased to function properly. The number of people who were unemployed grew. Begging and bread lines became familiar sights on city streets. Crime rates rose again. In addition, criminal gangs flourished. They were involved in prostitution, narcotics, gambling, pornography, robbery, and burglary.

The police tried to respond to the accompanying rise in property crime. But, they could do nothing to ease the economic problems at their root. Sometimes police efforts seemed futile. For instance, the popular press delighted in covering stories about crime and criminals (see Sass Brothers case study; PDF). The public criticized and mocked the police for their failures.

Economic downturn made radical political ideas, such as Nazism and Communism, more appealing to many disillusioned Germans. For most of the 1920s, the Nazi Party was a fairly insignificant organization. But the Great Depression changed German politics. For example, the Nazis had won less than 3 percent of the vote in the national parliamentary elections of 1928. In September 1930, however, they won a surprisingly large 18 percent. The Nazis were suddenly an important national political party. Their main ideological enemy, the German Communist Party, also grew during this time.

The Nazis and the Communists rejected parliamentary democracy. As a result, their presence in parliament was disruptive. They willfully kept the government from functioning. Both parties were also a visible presence on German streets. They battled each other as well as policemen. Political rallies, demonstrations, and marches defined the political atmosphere. The police were responsible for making sure these were orderly and safe events.

Politically-inspired street brawls became a regular feature of German life. Paramilitaries associated with German political parties battled in the streets. Hundreds of Germans died in the violence. The Nazi paramilitary was the SA (Sturmabteilung). The SA was particularly infamous. SA men did not limit their attacks to political opponents. For example, they vandalized businesses they considered Jewish. They also attacked unarmed Jews in the streets. Often, the SA used explosives and tear gas.

The police were unable to effectively control the paramilitary groups and stop the assaults. This situation further undermined police authority.

Police Attitudes Towards the Nazi Movement

In the years of the Weimar Republic, most active policemen were not Nazis. They were not members of the Nazi Party or of Nazi organizations. Many policemen saw themselves as professionals whose personal politics were not supposed to affect their work. In some cases, regulations limited police involvement in politics. Nonetheless, there were some policemen who aided the Nazi movement. For example, they provided the Nazis with information about upcoming police raids and other measures.

While not members of the far-right Nazi Party, many Weimar policemen were more inclined towards nationalist, right-wing political parties. They sympathized with some Nazi ideas, especially anti-communism. They also rejected parliamentary democracy and the Weimar Republic. Further, they wanted a return to authoritarianism. This form of government would bring a strong centralized state. It would also extend police power and end factional party politics. The Nazi Party promised all of this and more.

The End of Democracy

Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Many Germans, including many policemen, hoped that he would solve the problems of the Weimar Republic. This made it easy for policemen to eventually accept, if not welcome, the new Nazi regime.