The Nazi Kripo (Criminal Police)

The Nazi Kripo, or Criminal Police, was the detective force of Nazi Germany. They were responsible for investigating crimes such as theft and murder. During the Nazi regime and World War II, they became a key enforcer of policies based in Nazi ideology. The Kripo helped persecute and murder Jews and Roma. They also conducted the widespread arrest and imprisonment in concentration camps of people whom the Nazi regime categorized as asocials, professional criminals, and homosexuals.

Key Facts

-

1

The Nazi Kripo developed from criminal police institutions that existed across Germany prior to the Nazi regime.

-

2

The Nazi state gave the Kripo the power to eradicate their racial, social, and criminal enemies by preventively and indefinitely detaining them in concentration camps.

-

3

As part of Nazi Germany’s Security Police, the Kripo worked closely with the Gestapo, the regime’s repressive political police force.

The Criminal Police (Kriminalpolizei) was the detective police force of Nazi Germany. They are frequently referred to as the Kripo, an acronym for “Kriminalpolizei.” Police forces called Kriminalpolizei are still common in the German-speaking world today. In English, this type of police force is often called a detective force or criminal investigation department.

Before the Nazis

In Weimar Germany each German state had its own detective forces. These criminal police organizations used cutting edge forensic science and criminology. They were respected and mainstream in the international police community. Beginning in 1929, the Great Depression upended German economic, social, and political life. This had an impact on the work of the criminal police. In the last years of the Weimar Republic, detectives were overworked. They felt underappreciated as they attempted to respond to new societal conditions.

Some of these detectives turned to the Nazi Party. They believed the Nazis would solve what they perceived to be an array of social and legal problems impacting their professional and personal lives. The Nazis promised to be tough on crime. They rejected the Weimar criminal justice system as too mild. They also accused the government of letting newspapers turn criminals into celebrities through sensationalist crime stories. Several Berlin detectives embraced these positions and became active in the Nazi movement.

The Nazi Takeover, 1933

Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933. The new Nazi government dismantled the individual protections encoded in the Weimar constitution. It also expanded the powers of the police. This allowed the Nazi regime to change criminal police practice. A November 13, 1933 Prussian ordinance established “preventive detention” (Vorbeugungshaft) in a concentration camp. The ordinance applied to so-called professional criminals. Other German states followed suit. This decree fulfilled the longtime wishes of many criminal policemen and criminologists. It allowed the criminal police to detain people if they had been arrested and sentenced three times to at least six months for premeditated crimes.

Initially, the use of preventive detention was fairly limited. At the end of 1935 there were 491 alleged professional criminals in Prussian concentration camps. However, this relative restraint did not last long. As the Nazi police state expanded, Nazi policy towards criminals radicalized. And the Kripo’s use of preventive detention radicalized with it.

The Relationship between the Kripo and Gestapo

The Nazi regime created a strong, centralized police state under SS leader Heinrich Himmler. The system Himmler created had two complementary, plainclothes, investigative police forces. These were the Kripo and the Gestapo. In June 1936, they became known together as the Security Police (Sicherheitspolizei, or SiPo). The Security Police was led by Himmler’s deputy Reinhard Heydrich. One of the goals of centralization was to link these police organizations with each other. The intent was also to eventually unite them with the SS intelligence service (Sicherheitsdiesnt, Security Service, or SD).

Beginning in February 1938, Gestapo and Kripo candidates trained together in police academies. Policemen frequently transferred between these two, similar organizations. For the average person, it could be difficult to tell Gestapo and Kripo agents apart.

In September 1939, Himmler officially united the Kripo, Gestapo, and the SD. They were joined under the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, RSHA). The RSHA was commanded by Reinhard Heydrich. The Kripo became Office 5 (Amt V) in the RSHA. Until July 1944, the Kripo was under the leadership of Arthur Nebe. Nebe was a longtime Berlin detective and Nazi.

The Kripo housed a variety of specialized offices for combatting various criminal groups. These pertained to conartists, burglars, pickpockets, narcotics offenders, and international sex traffickers. Many of the offices pre-dated the Nazi era. However, there were also offices with a clear relationship to Nazi ideology. In October 1936, Himmler created a separate office called the Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion (Reichszentrale zur Bekämpfung der Homosexualität und der Abtreibung).

A Nazi Interpretation of Crime

Under the influence of Nazi ideology, the Kripo theorized and implemented a racial-biological interpretation of crime. The Nazis viewed criminals as hereditarily and racially degenerate. They believed criminals threatened the racial health of German society. According to the Nazi state and Kripo leaders, criminals needed to be forcibly removed from society to protect the People’s Community (Volksgemeinschaft).

In an August 1939 speech, Reich Criminal Police Director Nebe defined crime as “a recurring disease on the body of the people.” This disease was supposedly passed hereditarily from criminals and “asocial individuals” to their children. In the Nazi state, asocials were people who behaved in a way considered outside of social norms. The category included people identified as vagabonds, beggars, prostitutes, pimps, and alcoholics; the workshy (arbeitsscheu); and the homeless. This category also included Roma. The Nazi regime viewed Roma as behaviorally abnormal and racially inferior. Defining crime as a disease connected to certain groups radicalized Kripo practice.

Radicalizing Kripo Practice

The Kripo accepted the Nazi interpretation of crime. Many of its agents believed that they were obligated to target people whom they identified as biologically, racially, or hereditarily predisposed to criminality. In 1937, new decrees gave them the power to do so. These decrees expanded the practice of preventive detention. The Kripo were able to detain in concentration camps thousands of people who had never been convicted of a crime. Among those detained were people identified as asocials. The Kripo justified these measures with the idea that such persons or their offspring might become criminals in the future.

The Kripo broadly applied this practice. The effort coincided with and contributed to the expansion of the concentration camp system in 1937-1938. Beginning in 1937, those arrested by the Kripo as professional criminals and asocials made up a large percentage of the camps' inmates. They were often referred to by their camp badge colors, green for professional criminals and black for asocials.

After 1938, concentration camp inmates were detained under either Kripo preventive detention or Gestapo protective custody (Schutzhaft). Neither process was subject to judicial review. Both were intended to protect the racial, political, and social integrity of the People’s Community.

Between 1933 and 1945, the Kripo sent more than 70,000 people to concentration camps. At least half of these prisoners died as a result of Nazi brutality and neglect.

The Kripo, War, and Mass Murder

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany started World War II by invading Poland. War unleashed Nazi brutality and ultimately led to mass murder.

Kripo policemen and various other types of police units deployed alongside the German military. Most infamously, the Security Police and the SD, which included Kripo policemen, were organized into Einsatzgruppen. The Einsatzgruppen were responsible for identifying and neutralizing potential enemies of German rule. They were also tasked with seizing important sites and preventing sabotage. In addition, the Einsatzgruppen recruited collaborators and established intelligence networks. And together with other SS and police units, they shot thousands of Jews and tens of thousands of members of the Polish elite in 1939-1940.

Four Einsatzgruppen deployed during the German-Soviet war, which began in June 1941. Arthur Nebe, the leader of the Kripo, personally commanded one of these units. He led Einsatzgruppe B from June to November 1941. During Nebe’s tenure, this deadly unit was responsible for the mass murders of 45,000 people in the areas around Bialystok, Minsk, and Mogilev. Many of these victims were Jews.

The Kripo and Experiments with Poison Gas

An especially important and deadly office of the Kripo was called the Criminal Technical Institute of the Security Police (Kriminaltechnisches Institut der Sicherheitspolizei, KTI). This department was made up of forensic experts trained in science and engineering.

Kripo officials from the KTI developed early techniques to gas people en masse. In October 1939, Nebe instructed the KTI to experiment with methods of killing people with mental and physical disabilities. This effort was conducted in cooperation with the Euthanasia Program. A KTI chemical engineer and toxicology expert, Albert Widmann, tested possible killing methods. He ultimately suggested carbon monoxide gas. In fall 1941, Widmann helped create gas vans. The vans used carbon monoxide gas generated from exhaust fumes. Planners of the Operation Reinhard killing centers adopted this development. At Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka, large motor engines were used to generate carbon monoxide gas for the gas chambers.

In addition to mass shootings, the Einsatzgruppen and other SS and police units used such gas vans. The vans were used as a method to murder Jews and people with disabilities in Nazi-occupied eastern Europe.

The Persecution and Mass Murder of the Roma

The Kripo was responsible for the persecution and mass murder of the Roma. This effort built on a long-established pattern of European police forces tracking, harassing, and persecuting this community.

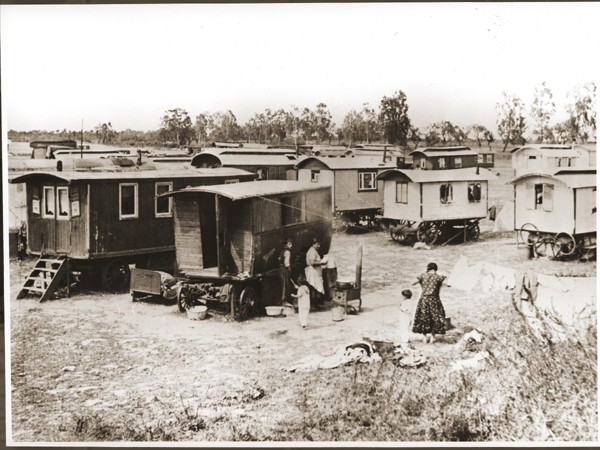

In 1933, the Kripo and other police in Germany began more rigorous enforcement of pre-Nazi legislation against those who followed a lifestyle labeled “Gypsy” (“Zigeuner”). The Nazis judged such people to be racially undesirable. In 1936, Himmler established the Reich Central Office for the Suppression of the Gypsy Nuisance (Reichszentrale zur Bekämpfung des Zigeunerunwesens) as part of the Kripo. In the 1930s, the Kripo established and administered camps for Roma in some parts of Germany. The most infamous of these early “Gypsy camps” (“Zigeunerlager”) was Marzahn, near Berlin. During the war, the Kripo expanded the internment of Roma. Subsequently, the Kripo also coordinated their deportation and murder.

Conclusion

Nazi Germany was defeated in 1945. Afterwards, many Kripo detectives tried to distance themselves from the Nazi state and its crimes. They claimed that they had done nothing wrong and that the Gestapo had committed all of the crimes. In their postwar telling, the Kripo had remained apolitical. They asserted they had simply carried out normal police work. But, this was a deliberate misrepresentation of facts. At an institutional and individual level, the Nazi Kripo was deeply complicit in the crimes of the Third Reich, including the Holocaust.