Mauthausen

Between 1933 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its allies established more than 44,000 camps and other incarceration sites (including ghettos). The perpetrators used these locations for a range of purposes, including forced labor, detention of people deemed to be "enemies of the state," and mass murder. Millions of people suffered and died or were killed. Among these sites was the Mauthausen camp.

Establishment of the Mauthausen Camp

Nazi Germany incorporated Austria in the Anschluss of March 11-13, 1938. Shortly thereafter, Reichsführer-SS (SS chief) Heinrich Himmler, SS General Oswald Pohl, the chief of the SS Administration and Business Offices, and SS General Theodor Eicke, the Inspector of Concentration Camps, inspected a site they thought suitable for the establishment of a concentration camp to incarcerate, as Upper Austrian Nazi Party district leader August Eigruber put it, “traitors to the people from all over Austria.” The site was on the bank of the Danube River, near the “Wiener Graben” stone quarry, which was owned by the city of Vienna. It was located about three miles from the town of Mauthausen in Upper Austria, 12.5 miles southeast of Linz.

At the end of April 1938, the SS founded a company, German Earth and Stone Works Inc. (Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke, GmbH-DESt), to exploit the granite which they intended to extract with concentration camp labor. In August 1938, the Inspectorate of Concentration Camps transferred approximately 300 prisoners, mostly Austrians and virtually all convicted repeat offenders or persons whom the Nazi regime classified as “asocials” from Dachau concentration camp to the Mauthausen site in order to begin construction of the new camp. By the end of 1938, Mauthausen held nearly 1,000 prisoners, still virtually all convicted criminals and asocials.

Prisoners in the Camp

Three months into World War II in December 1939, the number had increased to over 2,600 prisoners, primarily convicted criminals, "asocials," political opponents, and religious conscientious objectors, such as Jehovah's Witnesses.

After the Nazi regime initiated World War II, the number of prisoners arriving in Mauthausen increased dramatically and broadened in diversity. After the fall of France in June 1940, Vichy French authorities turned over to the German SS and police thousands of Spanish refugees, virtually all of whom had fought against General Francisco Franco's rebel troops during the Spanish Civil War, and who had fled to France after Franco overthrew the Spanish Republic in 1939. The SS and police incarcerated the overwhelming majority of the Spanish Republicans, more than 7,000, in Mauthausen in 1940 and 1941; individual members of the anti-Franco forces continued to trickle in to the camp until the last weeks of the war. Also incarcerated at Mauthausen were members of the International Brigades, most of them Communists of various nationalities, who had fought the Franco forces in Spain.

An estimated 197,464 prisoners passed through the Mauthausen camp system between August 1938 and May 1945. At least 95,000 died there. More than 14,000 were Jewish.

Prisoners in Mauthausen: Overview

During the war, the SS incarcerated more than 10,000 Soviet prisoners of war at Mauthausen, including 3,000 held at the Mauthausen subcamp Gusen. Nationals of virtually every German-occupied country in World War II came through Mauthausen. These included, among those prisoners who were registered:

- more than 37,000 non-Jewish Poles

- nearly 23,000 Soviet civilians

- between 6,200 and 8,650 Yugoslav civilians

- approximately 6,300 Italians after September 1943

- at least 4,000 Czechs

- in 1944, 47 Allied military personnel (39 Dutchmen, 7 British soldiers and 1 US soldier), all of them agents of the British Secret Operations Executive

Further, the SS transported other thousands of prisoners to Mauthausen to be murdered without ever being registered as prisoners in the camp.

Category III Camp

In January 1941, SS General Reinhard Heydrich, the chief of the Reich Main Office for Security (Reichssicherheitshauptamt; RSHA), designated Mauthausen as a category III concentration camp, in which the SS would incarcerate only those prisoners whom the RSHA deemed to be "severely incriminated, especially previously convicted criminals and asocials—that means protective detainees who have only remote potential for reform."

Jewish Prisoners

Before May 1944, the SS incarcerated relatively few Jews at Mauthausen. The total number of Jewish prisoners at Mauthausen between 1938 and the end of February 1944 was around 2,760. Most of them were reported dead by the end of 1943. From March through December 1944, at least 13,826 Jews arrived in Mauthausen, most of them Hungarian and Polish Jews and approximately 500 of them women. The SS had deported virtually all of them from Auschwitz-Birkenau and Plaszow camps to Mauthausen. In all, the SS registered 25,271 Jews in the Mauthausen camp complex, though the actual number of Jews, including arrivals during the last week of the war when the prisoner registration process broke down, may have pushed the number as high as 29,500.

Women Prisoners

Other than four Yugoslav women whom the SS brought to Mauthausen with 46 men to be shot in April 1942, the first female prisoners in Mauthausen were two dozen women from Ravensbrück, whom the SS transferred to provide sex for favored male prisoners. The women arrived in June 1942 and lived in the first bordello established in the Nazi concentration camp system. Over the next two years, the SS brought a few hundred women to Mauthausen either to kill them or to hold them temporarily in transit before transfer to other camps.

The first women registered as prisoners at Mauthausen (as opposed to Ravensbrück, arrived on October 5, 1943. With the arrival of more women in 1944, the Inspectorate of Concentration Camps classified Mauthausen as a women's concentration camp (Frauen-Konzentrationslager) on September 15, 1944. By the end of September 1944, 459 women were in the main camp:

- 392 political prisoners (non-Jewish)

- 38 Jehovah's Witnesses

- 29 so-called asocials

Six months later, on March 31, 1945, the SS reported 2,252 female prisoners in the Mauthausen system. Again, the majority were non-Jewish political prisoners (1,453), but the 608 Jewish women belonged to the second largest female prisoner category. Also reported among the female prisoners were:

- 43 Jehovah's Witnesses

- 79 Roma (Gypsies)

- 62 so-called asocials

- 5 women classified as Spanish Republicans

- 2 classified as convicted criminals

By February 1945, the SS had set aside three barracks in the main camp for female prisoners.

Operation K

In March 1944, the German Armed Forces High Command (OKW) issued a decree (so-called “Bullet Decree” or “Operation K”) mandating the transport of escaped and recaptured prisoners of war, other than British and US prisoners, to Mauthausen to be shot. The decree applied to all recaptured officers and those recaptured non-commissioned officers deemed no longer capable of work. The SS imprisoned the recaptured soldiers in barrack 20 in Mauthausen and shot some of them, while beating or starving others to death. The SS incarcerated and killed approximately 5,000 recaptured prisoners of war in Mauthausen within the framework of “Operation K.” Approximately 85 percent of the recaptured prisoners were Soviet soldiers; the remainder included Polish, Yugoslav, Dutch, French, and Belgian soldiers.

Sections of the Mauthausen Camp

The main Mauthausen camp (Stammlager) had three principal sections:

- Camp I, the original protective detention camp

- Camp II, the camp workshop area, where prisoners were forced to work, and which the SS later converted to prisoner barracks in spring 1944

- Camp III, built in the spring and summer of 1944 to accommodate the influx of Hungarian Jews

Located at the opposite side of the roll call square from Camp I was a chain of long stone buildings that housed various camp services such as the prisoners' kitchen, showers, laundry, the bunker and, eventually, the gas chamber. Nearby stood the crematoria facilities along with the site where the camp staff shot prisoners.

To the west, off the entrance road to the main camp, was the so-called infirmary camp. The SS originally constructed this facility in fall 1941 for Soviet prisoners of war; hence it was frequently referred to as the "Russian camp." From the spring of 1943, the camp authorities incarcerated ill or weak prisoners in this "infirmary" camp, where patients received little or no treatment and most eventually died.

East northeast of the main camp was the so-called tent camp, which consisted of 14 large tents with a total inner surface of 6,200 square yards. The camp authorities erected it in the autumn of 1944 to accommodate large groups of prisoners evacuated from concentration camps and forced-labor camps in the East. In the winter of 1945, the overwhelming majority of inmates in the so-called tent camp were Hungarian and Polish Jews.

The various camps were surrounded by walls and/or electrified wire. Watchtowers and SS guards surrounded the entire complex. The SS commandant's office and the barracks for the SS administrative personnel and guard units were located west of the camp.

SS Staff and SS Guard Detachment

Mauthausen's first commandant was SS Captain Albert Sauer, who presided over the establishment of the camp on August 1, 1938 and remained commandant until February 17, 1939. SS Colonel Franz Ziereis replaced Sauer and remained the commandant of Mauthausen until May 1945.

After March 1940, SS Captain Georg Bachmayer was 1st Protective Detention Camp commandant, with responsibility for the prisoners while they were inside the camp. In 1938-1939, the 4th Regiment ("Ostmark") of the SS Death's-Head Units (SS-Totenkopfverbände) guarded the perimeter of the Mauthausen concentration camp as well as prisoner work detachments deployed outside the camp. In 1940-1941, the guard unit, renamed SS Death's-Head Battalion (SS-Totenkopf-Sturmbann) and upgraded in strength to battalion size, was administratively subordinated to the Waffen SS, though the camp commandant still issued all operational orders to the battalion.

Beginning in 1942, the SS authorities deployed an increasing number of ethnic German Waffen SS recruits from Slovakia, Romania, Hungary, and Croatia to serve in the Death's-Head Battalions at all concentration camps, including Mauthausen. In 1944 and 1945, Trawniki-trained guards (some of them veterans of Operation Reinhard deportation operations or killing centers), air force, and naval as well as other military personnel, and, later, municipal police (Schutzpolizei) personnel and firefighters, served in the SS Death's-Head Battalion at Mauthausen and its subcamps.

Killing Operations at Mauthausen

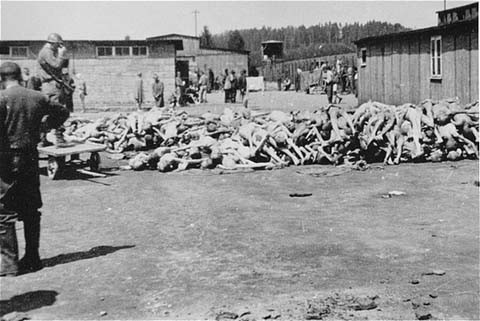

The Mauthausen camp authorities killed specially targeted groups of persons sent to Mauthausen for that purpose. They also killed those inmates deemed too weak or sick to work.

Gassing and Euthanasia

Several methods of killing were used. As in other camps, the Mauthausen authorities began to use gas as a means of killing in 1941–42. Like some other concentration camps, Mauthausen was equipped with a stationary gas chamber with the capacity to kill up to 80 people at a time by means of Zyklon B gas (prussic acid). In 1942, the Reich Security Main Office provided the camp authorities with a mobile gas van with the capacity to kill about 30 persons at a time. The SS dispatched, in addition, 2,960 prisoners from Mauthausen and 1,881 from Gusen, a total of 4.841 prisoners, to the Hartheim sanatorium and “euthanasia” killing center to be killed. German physicians and camp authorities had selected the victims within the framework of “Operation 14f13,” the extension of the Nazi “euthanasia policy” to the concentration camps.

Medical Experiments

German doctors subjected Mauthausen prisoners to pseudoscientific medical experiments, including testing levels of testosterone, experimenting with delousing chemicals, medicines for tuberculosis, and nutrition experiments. Camp physician Hermann Richter surgically removed significant organs—e.g., stomach, liver, or kidneys—from living prisoners solely in order to determine how long a prisoner could survive without the organ in question. Eduard Krebsbach, the executive camp doctor between autumn 1941 and autumn 1943, killed an undetermined number of prisoners by injecting phenol directly into their hearts.

Shooting, Hanging, Mistreatment, and Harsh Conditions

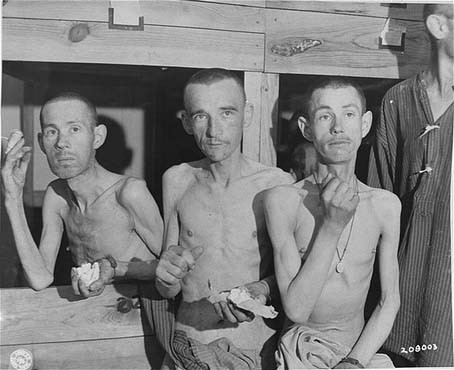

The SS also killed thousands of prisoners by shooting, hanging, and mistreatment. Tens of thousands more died as a direct result of the harsh living conditions in the camp, succumbing to starvation, exposure, and disease.

Forced Labor and Subcamps of Mauthausen

From the beginning, camp authorities deployed Mauthausen prisoners at forced labor, constructing the camp itself or at back-breaking work in the Wiener Graben stone quarry. As labor became increasingly scarce and the forced labor of camp inmates became increasingly important, especially in war-related industries, the number of prisoners incarcerated at Mauthausen and it subcamps steadily increased. On January 1, 1945, the Mauthausen camp system had 73,351 prisoners, 959 of them women. At this time Mauthausen incarcerated more male prisoners than any other concentration camp system in Nazi Germany, and had the third largest total prisoner population, behind Buchenwald and Gross-Rosen.

After the SS Economic-Administration Main Office (SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt; WVHA) assumed control of the Inspectorate of Concentration Camps and the camp system in March 1942, the SS established hundreds of subcamps throughout the so-called Greater German Reich. Subordinate to the main concentration camps, these subcamps were generally located in the vicinity of factories, stone quarries and mines, in which SS labor allocation officers deployed prisoners transferred from the main camp. Between 1940 and 1945, the SS authorities established nearly 50 subcamps in the Mauthausen concentration camp system, most of them in 1943 and 1944.

Among the most important subcamps were:

- Gusen (1940–1945)

- Steyr-Münichholz (1942–1945)

- Ebensee (1943–1945)

- Wiener Neudorf (1943–1945)

- Wiener Neustadt (1943, 1944–1945)

- Melk (1944–1945)

- the detention camp Gunskirchen (1945)

- Amstetten (1945)

Resistance at Mauthausen

As early as 1943, Spanish Republicans incarcerated inside Mauthausen, drawing upon their expertise as communist fighters and their contacts to Czech, French, and German members of the International Brigades, established small clandestine networks of resistance inside the camp. By the winter of 1944–45, these groups had established underground formations armed with weapons stolen from the camp arsenal.

During the course of 1944, French, Czech, and Austrian camp inmates, primarily communists, formed networks of self-help and resistance. In winter 1944–45 the formation of another resistance network of Czech, Polish, German, and Austrian inmates is documented for the “infirmary” camp. Their most effective activities involved providing food for starving prisoners, hiding prisoners temporarily, often in the infirmary, and protecting prisoners against arbitrary torture and mistreatment from Kapos.

Outside the Communist organizations, self-help resistance groups developed along lines of nationality. During the night of February 1–2, 1945, more than 400 Soviet prisoners of war incarcerated in barrack 20 killed the SS appointed prisoner administrators and broke out of the camp. German SS and police units, military units, units of the so-called People's Assault (Volkssturm), a national conscript militia of men over 60 and youths under 18 years of age, German police officials, SA, and Nazi Party formations engaged in a massive manhunt, which they dubbed cynically a “hare shoot.” The Germans recaptured or killed virtually all of the prisoners.

On March 23, 1945, several hundred female prisoners of subcamp Amstetten, whom the SS authorities had withdrawn to Mauthausen after the Allies bombed the train station in Amstetten and killed 34 women, refused to return to Amstetten, despite the threats of Protective Detention Camp Commandant Bachmayer. This was first and only case of a mass refusal to deploy to work.

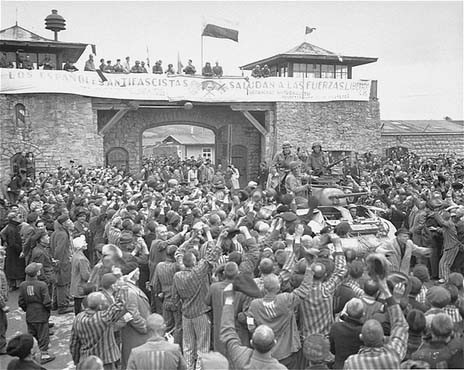

Liberation of Mauthausen

As Allied and Soviet forces advanced into Germany, the SS forcibly evacuated concentration camps near the front lines to prevent the liberation of large numbers of prisoners. Prisoners evacuated by train, by truck, and by forced march from Auschwitz, Sachsenhausen, and Gross-Rosen began arriving at Mauthausen in early 1945. As a result, the camp—as well as most subcamps—became lethally overcrowded, with existing dreadful conditions deteriorating still further. Thousands of prisoners died from starvation or disease. Typhus epidemics further reduced the camp's population.

Mauthausen's gas chamber remained operative until the very last days of the war. The SS murdered nearly 3,000 prisoners from the infirmary after a selection on April 20, 1945. The camp authorities carried out the last mass murder in the gas chamber on April 28, 1945. The victims were 33 Upper Austrian Social Democratic and Communist opponents of the regime.

On May 3, 1945, the SS abandoned the camp to the custody of a guard unit of 50 Viennese firefighters, who remained on the perimeter of the camp. Members of an “International Committee” formed by the prisoners in the last days of April administered the camp as units of the US Army arrived at the camp and secured the surrounding area on May 5. Further units, including the 11th Armored Division of the Third Army, arrived in the succeeding days.

Postwar Trials

US troops captured Mauthausen camp commandant Franz Ziereis on May 23, 1945, in a mountain hut. Ziereis was shot in the abdomen during a reported attempt to escape and died a day or two thereafter. Before his death, former camp prisoners interrogated him in the Gusen protective detention camp; this deathbed testimony was available to prosecutors at the Nuremberg Trial. Protective detention camp commandant Georg Bachmayer chose suicide as a means of escaping justice on May 8, 1945, after he shot his wife and two children.

Numerous members of the camp administrative staff and the guard units were prosecuted after the war. In a proceeding on the site of the Dachau concentration camp, a US Military Tribunal prosecuted deputy preventative detention camp commandant Hans Altfuldisch and 60 other defendants associated with Mauthausen in the spring of 1946. The tribunal convicted all 61 defendants, sentenced 58 to death and three to life imprisonment on May 13, 1946. On appeal, nine of the death sentences were commuted to prison sentences. US authorities executed 49 of the defendants and released the remaining twelve convicts in 1950 and 1951.

US military tribunals tried approximately 224 other persons associated with Mauthausen (officials, guards, prisoner functionaries, prisoners, and implicated civilians) in about 60 further proceedings at Dachau in 1947. Military judges convicted more than 90% of the defendants.

Austrian authorities prosecuted and convicted several defendants associated with Mauthausen in several trials after the war. The Federal Republic of Germany also conducted numerous proceedings against persons accused of Nazi crimes at Mauthausen and its subcamps. Perhaps the most extensive German investigation involved the proceedings against Karl Schulz and Anton Streitwieser, respectively, the chief of the political department in the main camp and the commandant of several Mauthausen subcamps. US Federal civil courts stripped four former Mauthausen guards of their US citizenship during the 1980s, after the Department of Justice's Office of Special Investigations brought suit against them for participation in Nazi-sponsored persecution.

An estimated 197,464 prisoners passed through the Mauthausen camp system between August 1938 and May 1945. At least 95,000 died there. More than 14,000 were Jewish.