Office of Special Investigations

Beginning in 1979, the Office of Special Investigations (OSI) opened hundreds of investigations and initiated proceedings of Nazi war criminals. These investigations lead to the denaturalization and/or removal of more than 100 Nazi offenders from the United States. Despite initial predictions that its work would soon be finished, OSI has been active for over 25 years.

Key Facts

-

1

Most proceedings initiated by OSI were against either auxiliary police forces serving in German-occupied territories, or guards at concentration camps and forced-labor camps.

-

2

In 2004, the US Congress expanded the jurisdiction of OSI to cover post-World War II offenders, who had immigrated to the US and obtained US citizenship, who had participated in genocide, torture, or extrajudicial killing abroad.

-

3

OSI donated more than 50,000 pages of trial documentation from litigation to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The documents described proceedings against US citizens or residents who allegedly participated in persecution on behalf of the Nazis or their allies.

The Office of Special Investigations (OSI), in the Criminal Division of the US Department of Justice, investigated and prosecuted cases against Nazi offenders from 1979 until 2010. (In March 2010, OSI merged with a new Department of Justice section, the Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section, while continuing with its original mandate.) OSI established a record as the most active and successful such law enforcement unit in the world. It was the only law enforcement unit of its kind to win awards from Holocaust survivor organizations.

OSI conducted civil proceedings, as criminal prosecutions in the Nazi cases were, in effect, barred by the ex post facto clause of the United States Constitution. Sanctions imposed as a result of successful civil prosecution by OSI were denaturalization (revocation of US citizenship) and deportation. The key element in OSI prosecutions was past participation of the defendant in Axis-sponsored persecution of individuals on the basis of race, religion, national origin, or political opinion. Naturalization fraud or visa fraud allegations were often included as well. There was no statute of limitations on civil immigration and naturalization fraud claims.

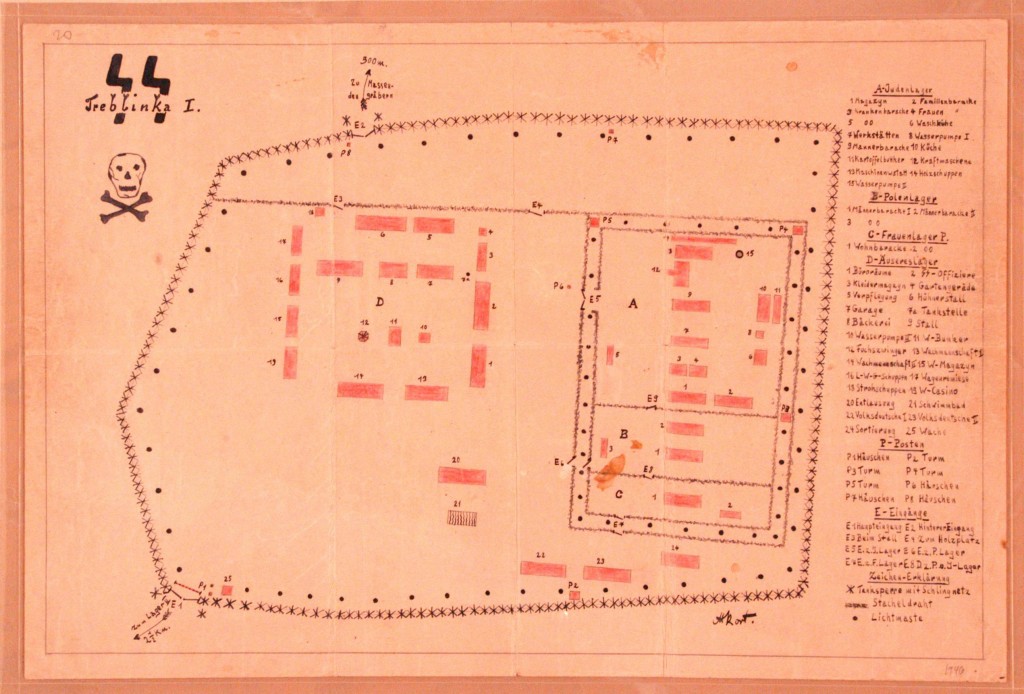

Despite initial predictions that its work would soon be finished, OSI was active for over 25 years. It opened hundreds of investigations and initiated proceedings leading to the denaturalization and/or removal of more than 100 Nazi offenders from the United States. In addition, with the assistance of the INS—and, since 2002, its successor, the Department of Homeland Security—OSI succeeded in blocking attempts made by more than 200 individuals suspected of participating in Nazi crimes to gain entry to the United States, among them the former United Nations Secretary General and later Austrian President Kurt Waldheim. The majority of persons against whom OSI initiated proceedings were either members of auxiliary police forces serving in German-occupied territories, or guards at concentration camps and forced-labor camps.

OSI and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum are "siblings" of a sort, having been conceived within the same political and moral context of the late 1970s. The Museum was of great assistance to OSI, both in granting access to key documentation that the Museum has microfilmed in archives in Germany, Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union, and in the commitment of the Museum to provide expert historian witnesses in prosecutions initiated and tried by OSI. The OSI played a critical role in drawing attention to the significant legal, moral, and ethical issues raised by Nazi crimes.

In December 2004, the US Congress expanded the jurisdiction of OSI to cover post-World War II offenders who obtained US citizenship after participating in genocide, torture, or extrajudicial killing abroad under cover of foreign law.