The Search for Perpetrators

By the late 1940s, concerns about the Cold War caused interest in prosecuting Nazi crimes to wane. Convicted perpetrators were released from prison, while many thousands more were never arrested or tried. Two major trials in the early 1960s led to greater public awareness of the Holocaust and renewed efforts to bring perpetrators to justice. Certain individuals and governments took the lead in these efforts, which forced hundreds of perpetrators to face accountability for their acts. The search for perpetrators continues, but as nearly all have died, only a small minority will ever have been brought to justice.

Key Facts

-

1

Thousands of perpetrators of Nazi crimes never faced justice in the immediate postwar period, and most of the perpetrators who had been convicted were set free in the 1950s.

-

2

The Adolf Eichmann trial in Israel in 1961 and the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial in West Germany from 1963 to 1965 attracted international interest. They raised awareness of the crimes of the Holocaust, leading to public support for achieving justice for the crimes.

-

3

In 1979, the United States Attorney General established the Office of Special Investigations to identify, investigate, and take legal action against participants in Nazi crimes who were in the United States.

Introduction

After World War II, thousands of Nazi perpetrators and collaborators were tried in Europe. Interest in prosecuting Nazi crimes soon diminished during the Cold War, however, and during the 1950s the surviving convicted perpetrators were set free. Many thousands of persons who had participated in the persecution and murder of innocent civilians did not face justice at all. Some changed their identities and fled from Europe. Many were able to live openly in their home countries and even take up their former professions.

Certain private individuals played an outsize role in the search for justice for Holocaust crimes, most notably Simon Wiesenthal and Beate and Serge Klarsfeld.

Simon Wiesenthal

Some Holocaust survivors sought to keep the issue of justice for Nazi crimes alive. Chief among these was Simon Wiesenthal. After being liberated from Mauthausen concentration camp, he worked for the War Crimes Section of the United States Army. In 1947 he opened the Jewish Historical Documentation Center in Austria to collect information about Nazi perpetrators who had escaped justice. Wiesenthal used the leads he collected to pressure governments to renew efforts to bring the perpetrators of Nazi crimes to justice. In some instances, his leads led to the arrest and prosecution of perpetrators.

The Eichmann and Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials

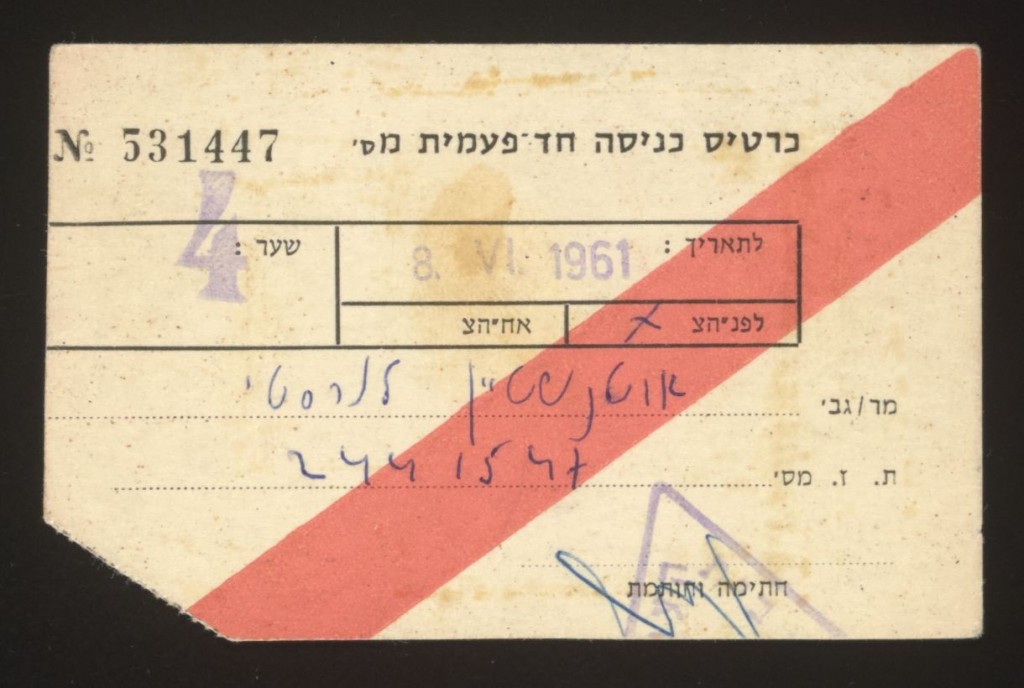

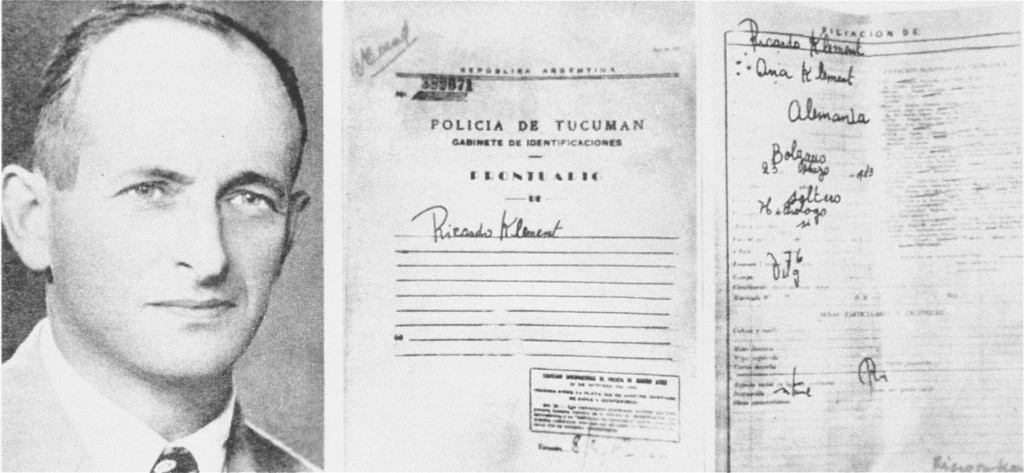

One of the perpetrators Wiesenthal sought was Adolf Eichmann, who organized the deportation of more than one million Jews to be killed in the Nazi “Final Solution” program. After the war, Eichmann escaped to Argentina under an assumed name. In 1960, acting on a tip from a West German prosecutor, Israeli intelligence agents abducted him and brought him to Israel to be prosecuted. The 1961 trial was televised and extensively covered by international media. The testimony of scores of witnesses to their terrible suffering and loss greatly increased public awareness of the horror and unique character of the Nazi genocide of the Jews.

Another event that raised awareness of the Holocaust particularly in West Germany was the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial. From 1963 to 1965, 22 German defendants faced charges that they had participated in heinous crimes at Auschwitz concentration camp complex, including the gassing of an estimated one million Jews at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The trial and public reaction to it helped persuade the West German government to extend the life of the agency responsible for investigating the perpetrators of Nazi crimes.

Office of Special Investigations

A tip from Simon Wiesenthal led to the discovery that Mrs. Russell Ryan, a housewife in Queens, New York, had during the war been Hermine Braunsteiner, a cruel SS woman guard at the Majdanek and Ravensbrück concentration camps. West Germany’s request to extradite her sparked allegations that many other so-called Nazi war criminals were living freely in the United States. It became evident that the government had failed in its duty to deny safe haven to Nazi perpetrators.

In 1979, the United States Attorney General established the Office of Special Investigations (OSI) in the Justice Department’s Criminal Division. Its sole mission was to detect, investigate and bring legal action against persons in the United States who, between 1933 and 1945, participated in Nazi-sponsored persecution on the basis of race, religion, national origin, or political belief. Because U.S. courts do not have jurisdiction to try Nazi crimes, OSI pursued Nazi persecutors for violations of immigration law, with the aim of removing them from the United States. In 2010, OSI was absorbed by the new Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section, which pursues both Nazi persecutors and perpetrators of more recent human rights violations who are in the United States. In its 31 years of operation, OSI brought successful legal action against 108 participants in Nazi persecution and prevented more than 180 suspected Nazi persecutors from entering the United States.

Beate and Serge Klarsfeld

Two other individuals who played an outsize role in the quest for justice for Nazi crimes are Beate and Serge Klarsfeld. They are best known for tracking down Klaus Barbie, called “the butcher of Lyon” for his crimes as SD chief in Lyon, France. After the war, he worked for US military intelligence, which helped him escape to South America. The Klarsfelds found him in Bolivia, living as Klaus Altmann. France extradited Barbie and in 1987 sentenced him to life in prison for crimes against humanity.

The Klarsfelds also contributed to the arrest and trial of several officials in the collaborationist Vichy government who were responsible for the deportation and deaths of Jews. These cases caused the French to reconsider their own role in Nazi crimes. In 1995, French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac acknowledged France’s complicity in the deportation of tens of thousands of Jews to their death in the Holocaust.

Josef Mengele

One of the most sought Nazi fugitives was Josef Mengele, referred to as the “Angel of Death” for his activities at Auschwitz-Birkenau. A physician, Mengele participated in selections of newly arrived transports of Jews, personally sending untold thousands of innocent civilians to their deaths in the gas chambers. He also conducted grisly medical experiments on Jews and Roma, with a particular focus on twin children, in an effort to prove Nazi racial theories. After the war, he fled to Argentina using an assumed identity, but soon reverted to his true name. Following Eichmann’s abduction, he fled to Paraguay and eventually to Brazil, where he drowned in 1979. A joint American, German and Israeli investigation led to the discovery of his remains in 1985. Advances in DNA analysis enabled investigators to confirm that the remains were Mengele’s in 1992.

Time Runs Out

Official efforts to bring the perpetrators of Nazi crimes to justice continued into the 21st century, particularly in Germany and the United States. Following successful legal proceedings by OSI, John Demjanjuk was extradited from the United States to Germany in 2009. In 2011, he was convicted as an accessory to the murder of 27,900 Jews at the Sobibor killing center. In 2015, a German court convicted Oskar Gröning as an accessory to the murder of 300,000 victims at Auschwitz. Although investigative efforts continue, any perpetrators still alive and able to stand trial are more than 90 years old. The majority of those who assisted in the crimes of the Holocaust will never be brought to justice.

Critical Thinking Questions

Is a perpetrator ever too old to prosecute? Is it ever too late for accountability?

Is it fair to the victims and their families not to prosecute? Does it serve justice to try some perpetrators when so many others have gone free?

Beyond the verdicts, what impact can trials have?