Oranienburg

Millions of people suffered and died in camps, ghettos, and other sites during the Holocaust. The Nazis and their allies oversaw more than 44,000 camps, ghettos, and other sites of detention, persecution, forced labor, and murder. Among them was the Oranienburg camp.

History

The Oranienburg concentration camp was established as one of the first concentration camps on March 21, 1933, overshadowed by the Day of Potsdam. After the “Night of the Long Knives,” the SA-run camp was taken over by the SS in July 1934 and dissolved a little later. The Oranienburg concentration camp is not to be confused with the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, which was established by the SS in July 1936 on the edge of the town of Oranienburg.

Initially SA-Regiment 208 (Standarte 208) established the Oranienburg concentration camp without notifying the responsible authorities in Berlin beforehand. The first inmates were 40 prisoners who were dragged to the small town 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) north of Berlin on the evening of March 21, 1933. The first concentration camp in Prussia was thus situated on the grounds of a former brewery on a main road in Oranienburg. From September 1933, subcamps existed at the Elisenau manor in Blumberg near Bernau and in Börnicke.

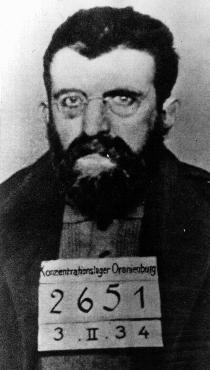

Only a few days after the establishment of the camp, SA Standartenführer Werner Schulze-Wechsungen transferred control of the camp to the Potsdam district president. Henceforth the camp as well as the guards were paid from tax money. In total, the German tax payer paid 280,000 Reichsmark (RM) between August 1933 and July 1934 to sustain the camp. Internment in the camp was initiated not only by the police and party authorities but also by local administrative authorities. Only because of its location in the town, the camp proved to be a “transparent concentration camp.” The town of Oranienburg had the political prisoners perform communal work. The camp commander, SA-Sturmbannführer Werner Schäfer, compiled an apologetic “Anti-Brown Book” (Anti-Braunbuch), in which he characterized allegations about the Oranienburg concentration camp as “atrocious propaganda.” Repeatedly he invited German and foreign journalists to tour the camp. A radio program “reported” from the concentration camp. The local press wrote extensively about the new institution. Also, movie theaters showed propagandistic

photos of the new concentration camp.

About 3,000 prisoners were deprived of their liberty in the Oranienburg concentration camp. The number of prisoners varied considerably. It rose rapidly until August 1933, from 97 to 911, but declined by the end of June 1934 to 271. The prisoners were mostly between the ages of 20 and 40, laborers, unemployed, from Berlin and from the area north of Berlin. Many were taken to Oranienburg after the dissolution of smaller Brandenburg concentration camps (including Alt Daber, Börnicke, Havelberg, and Perleberg) in June and July 1933. Prisoners from the concentration camps in Börgermoor, Lichtenburg, and Sonnenburg were interned at Oranienburg in September and October. Most of the inmates were members of the German Communist Party (KPD), the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and smaller left-wing organizations such as the Socialist Workers’ Party (SAP) and the German Communist Party Opposition (KPO). It is noteworthy that about 50 Jewish youths were also carried off to the camp from a home dedicated to advanced pedagogical ideas that was operated by the German Jewish Community Association (Deutsch-israelitischer Gemeindebund) in Wolzig. They had been abducted because of “Communist activities.”

In addition to mostly working-class prisoners, a few celebrities were held in Oranienburg, including the son of the former Reich president, Friedrich Ebert; the director of the Reich Broadcasting Association (Reichs- Rundfunk-Gesellschaft), Dr. Kurt Magnus; the chairman of the Prussian SPD parliamentary group, Ernst Heilmann; the editor in chief of the official KPD organ Rote Fahne, Werner Hirsch; the pacifist writers Kurt Hiller and Armin T. Wegner; and SPD Member of Parliament Gerhart Seger. Seger managed to escape in December 1933, fleeing first to Czechoslovakia and later to the United States of America. His book on the terror in Oranienburg was one of the first books written about the conditions in a concentration camp from firsthand experience.

Usually, the prisoners were held for two or three months in the camp. The main goal for holding the prisoners was to prevent representatives of the workers’ movement from being politically active. In principle, the killing of the prisoners was not intended. However, as the prisoners were exposed to the whims of their political opponents, some lost their lives. They became victims of mistreatment, torture, and lack of medical care. At least 16 prisoners, including the writer and anarchist Erich Mühsam, died in Oranienburg.

The guards at Oranienburg were recruited from the ranks of “proven” SA men, many of whom had previously been unemployed. Their numbers increased from March to summer from 50 to 170 but declined to 74 by June 1934. The camp command was composed of men of petit bourgeois background who were born in the first decade of the twentieth century in agricultural areas and had not participated in World War I. They were active in radical right- wing organizations in the first years of the Weimar Republic and had later joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP).

SA-Standartenführer Schulze-Wechsungen initiated the construction of the Oranienburg concentration camp. A farmer by training, he had joined the NSDAP and SA in 1925. He had a prior conviction for a raid in 1932 on a Berlin allotment settlement, which was mostly used by Communists. The camp commander was Werner Schäfer, a former member of the Free Corps “Olympia” and policeman, who had joined the NSDAP in 1928. At first SA-Sturmbannführer Hans Krüger was in charge of the “interrogation unit” (Vernehmungsabteilung). He was succeeded by SA-Sturmführer Hans Stahlkopf. Both revealed extreme brutality. Stahlkopf had joined the People’s Freedom Party (Völkische Freiheitspartei) in 1921 and had been a member of the Free Corps “Rossbach” from 1922 to 1927 and a member of the NSDAP since 1930. Between 1923 and 1931 he earned his living as the manager of a large farm. From May 1933, Stahlkopf was in charge of the Vernehmungsabteilung. Seger characterized him as “a stereotypical sneaky, especially disgraceful sadist.” After the Oranienburg concentration camp was dissolved, Stahlkopf became a member of the SSLeibstandarte Adolf Hitler. In 1935 he committed suicide.

Stahlkopf ’s predecessor, Krüger, a farmer by training, had joined the right-wing radical organization Wehrwolf in 1925 and the NSDAP in 1930. For unknown reasons he was relieved of all his official duties in October 1933. Having joined the SS in 1938, Krüger was appointed Kommandeur der Sipo und des SD (KdS) for the District of Galicia after the attack on the Soviet Union. Here he significantly participated in the systematic murder of the Jewish civilian population. His career reflects the radicalization of terrorist capacity of the Nazi regime. Krüger was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Münster Schwurgericht in 1968. Dr. Carl Lazar, a Bernau phycisian and SA functionary who was in charge of the camp’s “medical unit” (Sanitätsabteilung), regularly tried to cover up the mistreatment and murders at the Oranienburg concentration camp.

Criminal acts at Oranienburg were ignored by the German judicial authorities. Complaints against guards never resulted in an indictment. Also, after 1945, none of the perpetrators at the Oranienburg concentration camp were brought to justice. Then again, people who during the Nazi period distributed information about the criminal acts committed at the camp were repeatedly sentenced to imprisonment for spreading “atrocity propaganda” by the Berlin Regional Court’s Special Court (Sondergericht beim Landgericht Berlin). No one would have dared to criticize the conditions in the camp, which were well known through press coverage, the radio, and rumors.

Sources

The best overview of the history of the Oranienburg concentration camp is the collection of essays by Günter Morsch, ed., Konzentrationslager Oranienburg (Berlin: Ed. Hentrich, 1994). The essays provide details about various aspects of the concentration camp. Special attention should be paid to the contributions by Klaus Drobisch, “Oranienburg: Eines der ersten Konzentrationslager” and Martin Knop, Hendrik Krause, and Roland Schwarz, “Die Häftlinge des Konzentrationslagers Oranienburg.” A short overview on the topic is to be found in Bernward Dörner, “Ein KZ in der Mitte der Stadt: Oranienbug,” in Terror ohne System: Die ersten Konzentrationslager im Nationalsozialismus 1933–1935, ed. by Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel (Berlin: Metropol, 2001), pp. 123–138. An important work for putting the Oranienburg concentration camp into the context of the concentration camp system is Klaus Drobisch and Günther Wieland, System der NS- Konzentrationslager 1933–1939 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993).

The main sources on the history of the Oranienburg concentration camp system are contemporaneous publications that deal with the conditions inside the camp: Gerhart Seger, Oranienburg: Erster authentischer Bericht eines aus dem Konzentrationslager Geflüchteten (Karlsbad: Verlagsanstalt “Graphia,” 1934); Max Abraham, Juda verrecke: Ein Rabbiner im Konzentrationslager (Teplitz- Schönau: Druck- und Verlags- Anstalt, 1934); Werner Hirsch, Hinter Stacheldraht und Gitter: Erlebnisse und Erfahrungen in den Konzentrationslagern und Gefängnissen Hitlerdeutschlands (Zürich: Mopr- Verlag, 1934). The most important unpublished sources on the history of the Oranienburg concentration camp only became accessible after German Reunifi cation in 1989–1990. They are held today at the BLHA-(P), Rep. 35 G KZ Oranienburg Rep. 2 A Reg. Potsdam; the GStAPK, Rep. 90 P; and the BA- B, R 3001.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

BLHA-(P), Rep. 2 A Reg. Potsdam I Pol Nr. 1192, p. 72.; and Nr. 1193, p. 2.

-

Footnote reference2.

BLHA-(P), Rep. 2 A Reg. Potsdam I Pol Nr. 1193, pp. 2, 7; and Nr. 1192, p. 72.

-

Footnote reference3.

BLHA-(P), Rep. 2 A Reg. Potsdam I Pol Nr. 1183, p. 198.

-

Footnote reference4.

BLHA-(P), Rep. 2 A Reg. Potsdam I Pol Nr. 1191, p. 21.

-

Footnote reference5.

BLHA-(P), Rep. 2 A Reg. Potsdam I Pol Nr. 1193.

-

Footnote reference6.

Winfried Meyer, Günter Morsch, and Roland Schwarz, “Einleitung,” in Konzentrationslager Oranienburg, ed. Günter Morsch (Berlin: Ed. Hentrich, 1994), p. 9.

-

Footnote reference7.

BA-DH, ZD 9209 A. 13.

-

Footnote reference8.

Werner Schäfer, Konzentrationslager Oranienburg: Das Anti-Braunbuch über das erste deutsche Konzentrationslager (Berlin: Buch- und Tiefdruck-Gesellschaft, 1934).

-

Footnote reference9.

Werner Schäfer, Konzentrationslager Oranienburg: Das Anti-Braunbuch über das erste deutsche Konzentrationslager (Berlin: Buch- und Tiefdruck- Gesellschaft, 1934), pp. 106–107; BLHA-(P), ehem. Oranienburg Nr. 8.

-

Footnote reference10.

Gerhart Seger, Oranienburg: Erster authentischer Bericht eines aus dem Konzentrationslager Geflüchteten (Karlsbad: Verlagsanstalt “Graphia,” 1934), p. 29.

-

Footnote reference11.

For example, OBGZ, March 29, 1933.

-

Footnote reference12.

Photographs by the Emelka-Filmgesellschaft taken on April 13, 1933, were shown at movie theaters in Berlin and Oranienburg.

-

Footnote reference13.

Seger, Oranienburg.

-

Footnote reference14.

BLHA-(P), former Oranienburg Nr. 4 and Nr. 8.

-

Footnote reference15.

Seger, Oranienburg, p. 31.