Ritchie Boys

The “Ritchie Boys” is a term used for American soldiers who trained at Camp Ritchie during World War II. At Camp Ritchie, military instructors taught intelligence-gathering collections and analysis to approximately 20,000 soldiers. Several thousand of these soldiers were Jewish refugees who had immigrated to the United States from Europe to escape Nazi persecution.

Key Facts

-

1

The Ritchie Boys got their name because they received instruction in military intelligence at Camp Ritchie, near Cascade, Maryland, during World War II.

-

2

Approximately 2,000, or ten percent, of the soldiers who trained at Camp Ritchie were German Jewish refugees. Their fluency in the German language and knowledge of German customs enhanced their intelligence work.

-

3

After graduating from Camp Ritchie, the soldiers were assigned to different military units in North Africa, Europe, Asia, and the United States. They uncovered important information that saved the lives of thousands of other American soldiers during World War II.

Note on Terminology

Soldiers who trained at Camp Ritchie were not commonly called “Ritchie Boys” during World War II. The term became widely used after German filmmaker Christian Bauer released a documentary called “The Ritchie Boys” in 2004.

Some historians have used “Ritchie Boys” to refer to all of the approximately 20,000 soldiers who trained in intelligence at Camp Ritchie during World War II. Other historians have used the term for only a portion of that group: the nearly 2,000 German Jewish refugees who trained at Camp Ritchie after immigrating to the United States to escape Nazi persecution.

Establishment of the Camp

In early 1941, the United States was still officially neutral in World War II. Great Britain and Germany had been at war for more than a year. The Axis Powers, including Germany, Italy, Japan, and their collaborators, controlled much of Europe and Asia. Americans debated whether the United States should remain neutral or if the country should do more to support Great Britain and the other Allied forces.

The United States instituted a military draft. The US Army grew from 200,000 soldiers in 1939 to 1.4 million in 1941. But that Army did not have a program for training officers and noncommissioned officers to gather or analyze battlefield intelligence, particularly through interrogation of prisoners of war. General George Marshall, the chief of staff of the US Army, worried that the United States military needed to prepare soldiers to do tactical intelligence work. In April 1941, Great Britain agreed that the United States could send military observers to learn from British combat units. Upon returning to the United States, the officers recommended the establishment of centralized training for intelligence staff.

The Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, approved of a plan on May 26, 1942, to create a specialized training camp. Army leaders wanted the new camp to be near Washington, DC. They also needed it to be suitable for field maneuvers and training exercises where soldiers could practice what they were learning in forests and on mountains.

The War Department selected Camp Albert C. Ritchie, a 632-acre camp near Cascade, Maryland. The camp had been used by the Maryland National Guard since 1926 and had been named after the governor of Maryland at the time. The state of Maryland leased the camp to the US government. The War Department shortened the name of the camp to “Camp Ritchie.” It was also known as the MITC, or the Military Intelligence Training Center. Colonel Charles Banfill of the US Army Air Corps served as the camp’s first commanding officer. The camp officially opened on June 19, 1942. The camp’s flag showed a German military map and a silver star with the letters “MITC” and a motto in Latin: “Fas est et ab hoste doceri” (“You must learn from the enemy”).

At first, the camp could only house troops in tents. There were a few stone buildings, but the War Department needed the camp to be able to train soldiers year-round. The military spent five million dollars to construct new housing, new classrooms, new cafeterias (known as “messes”), and a new water system. The camp had a theater, two tennis courts, and two man-made lakes used for boating and swimming. It also had a chapel, which was used for Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish religious services. Many soldiers also attended religious services or recreational events in nearby Hagerstown, Maryland.

During Camp Ritchie’s operation, the military also leased local areas. They utilized 1,700 acres of the local Catoctin recreation park for additional outdoor training. The military also used a hangar at the nearby Waynesboro municipal airport to house planes for aerial photograph interpretation training. Camp instructors used privately-owned farmland near the camp while training soldiers to read maps, navigate unfamiliar areas, and do terrain analysis.

Recruiting Soldiers

The first class of 36 student soldiers began their training at Camp Ritchie on July 27, 1942. They were all officers in the military. Soon, though, classes were a mix of officers and enlistees. The students came from all over the country. Some were volunteers and others had been drafted. They were required to be physically fit, be able to get along with others, and have at least a high school education. Many of the Camp Ritchie students had started college or had college degrees.

There was no formal application process. Many students were fluent in multiple languages and were pulled from other Army units and sent to Camp Ritchie. After English, German was the most common language spoken by the soldiers. As the War Department planned how the United States would fight in Europe and in the Pacific, soldiers with different language skills were sent to Camp Ritchie. For example, as the Allies began to plan the D-Day invasion, more soldiers with French language skills arrived for training.

At Camp Ritchie, groups of soldiers trained at the same time were called “classes.” There were 31 classes of soldiers. After the first small class, the numbers grew, and between January 1943 and March 1945, each class had an average of nearly 600 students. The classes overlapped, and there were often more than 1,000 soldiers training at Camp Ritchie at the same time. One class would begin training while another class was halfway through. The final class of students graduated on September 22, 1945, after the end of World War II.

In total, 15,235 soldiers attended the eight-week training at Camp Ritchie. Only 11,637 of those soldiers finished the course and graduated. The training was difficult, and not everyone passed. But some soldiers were also pulled from training if their language skills were needed immediately for the war effort.

Intelligence Training

To keep the training as relevant as possible, Camp Ritchie instructors constantly adjusted their instruction to meet the military’s needs. At first, the instructors were military staff from other training camps. Upon graduation, some exceptional students stayed to teach. Some instructors transferred to Camp Ritchie after serving in North Africa, Europe, or the Pacific, using their battlefield knowledge as a teaching tool.

Each class, or group, of students attended eight weeks of training. For the first five weeks, students took classes on many different topics. In “Terrain Intelligence,” they learned to read and draw accurate maps, as well as how to navigate. In “Signal Intelligence,” instructors taught them how to set up and use communications equipment, as well as how to identify and use enemy equipment. All soldiers also had to learn Morse code. A few were even trained to work with carrier pigeons.

The students were trained to write accurate and useful intelligence reports. They had to learn how their own and enemy armies were organized, and to identify different uniforms, weapons, tanks, and planes. Instructors taught aerial photograph interpretation so that soldiers could gather intelligence from photos taken by planes. Camp Ritchie students learned close-combat fighting techniques from an instructor named Frank Leavitt, who had been a professional wrestler. They learned how to identify and remove booby-traps and how to conduct raids and searches. All students also participated in two and eight-day field exercises, where they were dropped in unfamiliar areas and tested on the skills they had learned.

For the final three weeks, students received specialized training depending on their skills and on the military’s needs. More than 3,000 students were given advanced photo interpretation training. Many of them had been pilots, engineers, or photographers before entering the military. They looked at aerial photographs and learned how to identify camouflaged vehicles and enemy units. Photos were often taken on the battlefield and sent back to Camp Ritchie to give soldiers experience analyzing photos that had been taken only days before.

Many of the 2,011 students trained in counterintelligence were members of the Counterintelligence Corps (CIC), which was a separate part of the US Army. In August 1944, the CIC began sending all new agents training for overseas service through Camp Ritchie’s eight-week program. Some of these soldiers had been lawyers or private investigators before the war. They received special training in how to identify potential enemy spies and saboteurs.

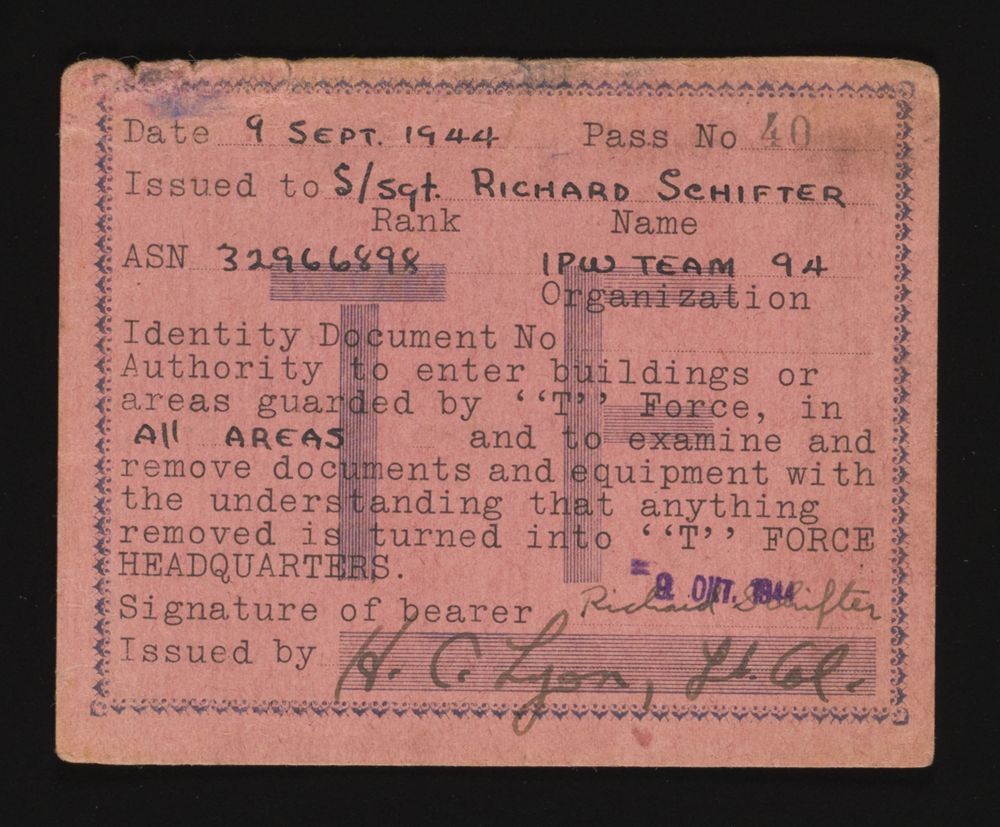

Most of the Camp Ritchie trainees–5,264 of them–spent their three weeks of special training learning how to interrogate prisoners of war. They were split up by language, with 2,872 soldiers working primarily in German, 326 in Italian, and 2,066 in the dozens of other languages spoken at Camp Ritchie and important to the US military, including Russian, Greek, Norwegian, Polish, and Arabic. The interrogators were told they could never physically assault a prisoner of war, but they could coerce the prisoners to talk in other ways. For instance, because many German soldiers were afraid of being captured by the Soviet military, an interrogator might dress as a Soviet officer and pretend to be ready to take over if the prisoner didn’t talk to the American interrogator.

When training, soldiers were first split into pairs and interrogated each other. They were given instructions on how to gain information. Soldiers were told to begin by asking a question for which they already knew the answer. That way, if the captured prisoner refused to answer, the soldier could act like he already knew everything anyway. Staff at the camp, including professional actors, played difficult prisoners or spoke in dialects that were hard for the interrogators to understand. Sometimes, the military even brought real prisoners of war to the camp so the students could practice their technique. At the end of training, the trainees had to successfully interrogate one of their instructors in order to graduate.

Once the eight weeks of training were over, the soldiers were given new assignments. Those who trained as interrogators were formed into teams consisting of two officers and three or four enlisted men. After graduation, many soldiers were either sent for further training, assigned to divisions already fighting in North Africa, Europe, or the Pacific, or given jobs in secret intelligence agencies in the United States or Great Britain.

Camp Ritchie Community

Camp Ritchie was much more diverse than many other military camps. Forty-four percent of the soldiers at Camp Ritchie were born outside of the United States, and 19% were born in Germany. Many of the soldiers spoke multiple languages, and it was not uncommon to hear a variety of languages spoken around the camp.

Although the US Army was segregated during World War II, at least 48 Black soldiers trained alongside white soldiers at Camp Ritchie. Even in training, they had to sleep in segregated barracks. However, most Black soldiers were later unable to use their new skills, as the military prohibited them from commanding white troops.

There were also soldiers at the camp who were not counted among the approximately 20,000 “Ritchie Boys.” More than 400 soldiers, including many Native American troops, worked for the Composite School Unit (CSU), which was heavily involved in the instruction. They demonstrated various scenarios, pretending to be enemy units, potential spies, or prisoners of war. Many of these soldiers also spoke multiple languages and became experts in German or Japanese military tactics and weapons in order to demonstrate various situations. Professional actors performed scripted scenes as a teaching tool, even holding pretend Nazi mass rallies for trainees to witness. Camp Ritchie contained a fake German village which included a house with one of the walls removed so students could watch the staff demonstrate tactics for capturing and interrogating potential enemies.

Members of the Womens’ Army Corps (WAC) were also stationed at Camp Ritchie beginning in September 1943. Many of them worked in the camp administration or as secretaries, but some also took part in training exercises, giving interrogators practice interviewing women. In total, approximately 200 WACs served at Camp Ritchie. Twelve WACs took courses, including in photo interpretation and Order of Battle. Some of these women later served in Europe and in the Pacific, acting as interpreters and intelligence specialists. A few even taught courses at Camp Ritchie.

In the fall of 1944, the US military set up the Pacific Military Intelligence Research Section (or PACMIRS) at Camp Ritchie. At least 40 of the PACMIRS soldiers were Nisei, or first generation Japanese American soldiers. This unit worked to identify and translate important captured Japanese documents.

Additional Nisei soldiers arrived in the camp in summer 1945, including wounded veterans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 442nd was a Japanese American unit and the most highly decorated unit for its size and length of service in the history of the US military. Some of these soldiers had been imprisoned with their families in so-called “relocation camps” by the US government and had volunteered for military service. Like Black soldiers, Japanese American soldiers could only serve in segregated units.

The US military did not send Japanese American infantry units to the Pacific theater, so these soldiers had fought only in Europe. Still, at Camp Ritchie, they were separated into Mobile Intelligence Training Units (MITU). The MITUs were assigned to learn about Japanese equipment, battle tactics, and to prepare to train American soldiers throughout the country in preparation for a US invasion of Japan. Some Japanese Americans were aware that they had been assigned to a MITU simply because of racist assumptions about their Japanese ancestry. However, when ordered to wear Japanese Army uniforms and pretend to be the enemy in field exercises, many refused, pushing back against the Army's prejudice. The war in the Pacific ended before the MITUs were deployed, but many of the Japanese American soldiers trained at Camp Ritchie later served in the Counterintelligence Corps or in other occupation government functions in Japan.

Advanced Intelligence Work

After graduating from training at Camp Ritchie, some soldiers received advanced intelligence training or were assigned to work in top secret intelligence installations.

One of the most common advanced courses was called “Order of Battle.” Although all Ritchie Boys undergoing the eight-week training program received basic information about the organization of enemy military units, some graduates were assigned to an additional four weeks of advanced instruction. They had to memorize up-to-date information about the various enemy commanders, unit structure, location, and weapons. Camp Ritchie held 22 four-week “Order of Battle” courses. Some of the 899 students were graduates of the eight-week program, while others came to the camp just for this training.

Some graduates received additional training at Camp Sharpe, located in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, not far from Camp Ritchie. These men were taught psychological warfare tactics, including how to operate mobile radio broadcasting equipment and how to write Allied propaganda aimed at enemy soldiers and civilians.

Order of Battle and Camp Sharpe trainees were trained using information gathered primarily by the Military Intelligence Research Section (MIRS). This secret agency, run jointly by the US and British militaries, was responsible for gathering and disseminating current information, both to Allied commanders in the field and to “Order of Battle” trainees.

Fort Hunt, also known as PO Box 1142, was a secret installation near Mt. Vernon, south of Alexandria, VA, that served as the MIRS headquarters in the United States. MIRS staff wrote reports on various important military topics based on the intelligence they had gathered. Most of the American staff of MIRS were Camp Ritchie graduates. Some Ritchie graduates also participated in the interrogation of important German prisoners of war, which also took place at Fort Hunt.

Camp Ritchie also trained Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) agents with specialized courses that were shorter than the eight-week training program. Their training focused on how to detect spies and saboteurs. Members of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor organization to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) trained near Camp Ritchie. They learned how to take on false identities, sabotage equipment, and survive behind enemy lines. After graduating from the eight-week course, at least 275 Ritchie Boys served in the CIC or OSS.

Refugee Ritchie Boys

Approximately 2,000 Ritchie Boys were refugee soldiers who had escaped Nazi persecution and violence and had immigrated to the United States. Many of them trained as prisoner of war interrogators. Their fluency in German and knowledge of German customs assisted them in their work. Unlike Japanese American soldiers, who were not allowed to serve in the Pacific theater, German and Austrian refugee soldiers were specifically trained for service in Europe.

These soldiers were often highly motivated to return to Europe to defeat Nazism. Some had left loved ones in Europe and hoped to reunite with them—or to make sure the Nazis and other perpetrators were brought to justice.

Upon graduating from Camp Ritchie, refugee soldiers traveled to the courthouse in Hagerstown, Maryland, where they naturalized as American citizens. Non-citizen soldiers were often able to become US citizens because of their military service. Many also “Americanized” their names, in part to prevent the Nazis from being able to identify them as Jewish if they were captured.

Ritchie Boys at War

Graduates of Camp Ritchie served throughout World War II. Some students were pulled from training to participate in the Allied war in North Africa in 1942 and 1943. Sixty-three men who had completed the four-week “Order of Battle” training were assigned to the 101st Airborne Division and parachuted into France on June 6, 1944, as part of the D-Day invasion. Others landed on the beaches, or came ashore in the days after the invasion. They used their skills to interrogate newly captured prisoners, gain information from local civilians, and provide important intelligence services. Some also participated in the liberation of concentration camps in spring 1945.

Numerous Ritchie Boys were killed in action. Murray Zappler and Kurt Jacobs were both Jewish refugees born in Germany and members of an interrogation team. On December 16, 1944, their unit captured a group of German soldiers, whom Zappler and Jacobs interrogated. A few days later, a German attack forced their American unit to surrender. The German soldiers identified Zappler and Jacobs, who were separated from the other American captives and executed. Others were killed in battle, in bombings, or became prisoners of war.

Others fought in the Pacific Theater. Ritchie Boys participated in the assaults on Guadalcanal, Okinawa, Iwo Jima, and the Philippines. Private Leonard Bostrom, a member of the 10th class at Camp Ritchie, was killed while attacking an enemy stronghold in the Philippines to save his unit. He posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

Closure of Camp Ritchie

In June 1946, exactly four years after the United States government leased Camp Ritchie, it returned the camp to the state of Maryland. The camp was used by the Maryland National Guard until November 1951, when the US government leased it again and renamed it Fort Ritchie. Fort Ritchie closed in 1998.

Post-War Ritchie Boys

After World War II ended, some Ritchie Boys stayed in Europe. They helped to reestablish newspapers, worked in denazification, and interrogated prisoners of war in search of high ranking Nazi officers posing as soldiers or civilians. Some participated as interrogators or translators at the Nuremberg trials and other Allied war crimes trials. The information and early historical evidence they gathered revealed important details about the Holocaust. Ritchie Boys in the Pacific also served in the US occupation of Japan.

A number of Ritchie Boys continued to serve in the US military. The Ritchie Boys who decided to leave the military also went on to important careers. Some served in US intelligence agencies. Others became congressmen, governors, ambassadors, college professors, or ran companies. They had families and children and continued to enrich the United States.

Ultimately, nearly 20,000 soldiers trained at Fort Ritchie, either as members of eight-week training classes or in specialized instruction like the Military Intelligence Training Units or Order of Battle specialists.

In August 2021, the United States Senate passed a bipartisan resolution honoring the service of the Ritchie Boys. In 2022, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum named the Ritchie Boys as the recipient of the Museum’s highest honor, the Elie Wiesel Award, for “their remarkable actions and heroism in helping to end the war and the Holocaust.”