The 11th Armoured Division (Great Britain)

The British 11th Armoured Division's discovery of the Bergen-Belsen camp and the horrendous conditions there had a powerful impact on public opinion in Great Britain and elsewhere. When the 11th Armoured Division entered the camp, its soldiers were totally unprepared for what they found.

The British 11th Armored Division Advances

In July 1944, soon after the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day (June 6, 1944), the British 11th Armoured Division broke out of the Normandy beachhead and advanced into France, before turning northward to Belgium. On September 4, 1944, the unit captured the city of Antwerp. Soon thereafter, the 11th Armoured Division pushed forward into the German-occupied Netherlands. In March 1945, it crossed the Rhine River, and by the end of the war had advanced to the northeast and captured the German city of Lübeck.

Entering the Bergen-Belsen Camp

As it drove into Germany, the British 11th Armoured Division occupied the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on April 15, 1945, following an April 12 agreement with the retreating Germans to surrender the camp peacefully. When the 11th Armoured Division entered the camp, its soldiers were totally unprepared for what they found. Inside were approximately 55,000 emaciated and ill prisoners in desperate need of medical attention. Thousands of corpses in various stages of decomposition lay littered around the camp.

so I realize I am really alive and we were liberated. It was the English army that liberated us.

—Fela Warschau

Conditions in the Camp

As Nazi Germany fell under the onslaught of the Allied and Soviet troops, the SS had evacuated prisoners on death marches from outlying camps to the interior of the dwindling Reich. In 1944, the first large transports from Auschwitz and other camps arrived at Bergen-Belsen, transforming the camp in size and function. By December, it held more than 15,000 inmates, many of them women. In the following months, the prisoner population dramatically increased as Allied and Soviet troops drove deeper into Germany. By March 1945, the number of inmates had swelled to over 41,000. In the following weeks, the SS delivered transports of prisoners from the Neuengamme and Dora-Mittelbau camps.

Conditions within the grossly overpopulated camp in 1945 were horrendous. Disease, particularly typhus, dysentery, and tuberculosis, was rampant. In the first four months of the year, tens of thousands of prisoners died, victims of Nazi brutality and neglect. Starvation and malnutrition led to death and incidents of cannibalism. In the days before liberation, the prisoners had been left without food or water. More than 13,000 inmates died in the three months following liberation.

I've been here eight days, and never in my life have I seen such damnable ghastliness.

—Reverend T.J. Stretch

Impressions of the Camp

British troops were shocked and horrified by what they encountered when they entered the camp on April 15, 1945. Lieutenant-Colonel R. I. G. Taylor, the Commanding Officer of the 63rd Anti-Tank Regiment, recalled his impressions of the camp at liberation:

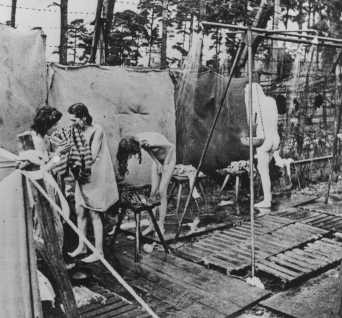

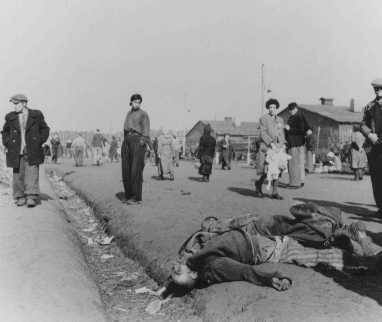

A great number of them [the inmates] were little more than living skeletons with haggard yellowish faces. Most of the men wore a striped pyjama type of clothing—others wore rags, while women wore striped flannel gowns or any other clothing they had managed to acquire. Many of them were without shoes and wore only socks and stockings. There were men and women lying in heaps on both sides of the track. Others were walking slowly and aimlessly about—a vacant expression on their starved faces.

Relief Operations

Huts were almost impossible to go near. They were full of tangled masses of people who had died slowly and painfully of starvation and disease, writhing in agony, helpless in puddles of excrement.

Immediately, the British army turned over relief operations to Brigadier H. L. Glyn-Hughes, the Deputy Director of Medical Services for the British Second Army. He and his staff were faced with the monumental task of feeding tens of thousands of former prisoners, reducing the mortality rate, and preventing the spread of infectious diseases. On April 16, the first deliveries of food and water arrived. The death rate, however, remained high, averaging 300 to 400 deaths per day. Almost a month later, the relief teams had reduced this figure to less than 100 deaths per day. In addition to the thousands of corpses found by the British liberators upon their arrival, more than 13,000 former prisoners died during the three months after liberation.

The medical personnel discovered countless individuals who were to weak to move out of the filthy lice-infected barracks. The stench of poor sanitation, disease, and death filled the air and nostrils of the liberators. Glyn-Hughes informed the court trying the Bergen-Belsen SS guards that:

The conditions were indescribable because most of the internees were suffering from some form of gastro-enteritis and they were too weak to leave the hut. . . . The compounds were absolutely one mass of human excreta. In the huts themselves the floors were covered and the people in the top bunks who could not get out just poured it onto the bunks below.

To save as many of the former inmates as possible, the British army began evacuating the camp’s population to nearby German army barracks, which had been commandeered and transformed into makeshift hospitals. Each day, more than 1,000 people were removed to the new facilities and the barracks burned down. On May 21, 1945, the British army held a ceremonial burning of the last barracks buildings at the camp.

Images of the Camp and their Impact on Public Opinion

The discovery of the Bergen-Belsen camp and the horrendous conditions there made on powerful impact on public opinion in Great Britain and elsewhere. One member of a British Army Film and Photographic unit recalled the masses of unburied corpses:

The bodies were a ghastly sight. Some were green. They looked like skeletons covered with skin—the flesh had all gone. There were bodies of small children among the grown ups. In other parts of the camp there were hundreds of bodies lying around, in many cases piled five or six high.

Burying the bodies became an overwhelming task. The British forced SS guards to remove and inter the corpses in mass graves, but soon bulldozers had to be requisitioned to complete this task. These images of the dead soon appeared in newspapers, newsreels, and magazines, shaping the ways the British and US public viewed Nazism and Nazi racial policy. Bergen-Belsen became a watchword for Nazi inhumanity and brutality.

"Can I Do Something For You?"

Bring me warm socks.

—Bella Jakubowicz Tovey

Critical Thinking Questions

What challenges did Allied forces face when they encountered the camps and sites of other atrocities?

What challenges faced survivors of the Holocaust upon liberation?