The Great Depression

The “Great Depression” is the term used for a severe economic recession which began in the United States in 1929. It had far-reaching effects around the globe, especially in Europe. Many factors, including World War I and its aftermath, set the stage for this economic disaster.

Key Facts

-

1

The Great Depression was a contributing factor to dire economic conditions in Weimar Germany which led in part to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party.

-

2

Within the United States, the repercussions of the crash reinforced and even strengthened the existing restrictive American immigration policy.

-

3

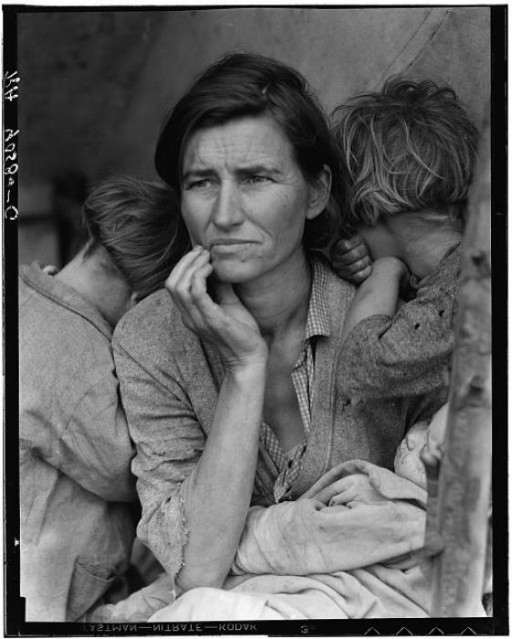

By 1933, approximately 15 million people (more than 20 percent of the U.S. population at the time) were unemployed.

Factors Leading to the Great Depression

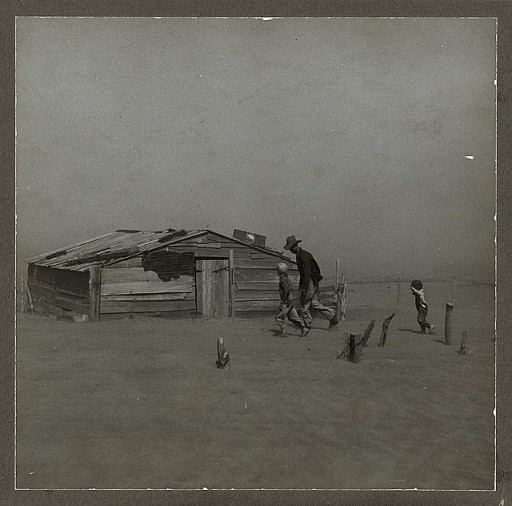

The stock market crash on October 24, 1929, marked the beginning of the Great Depression in the United States. The day became known as "Black Thursday." Many factors had led to that moment. World War I, changing American ideas of debt and consumption, and an unregulated stock market all played pivotal roles in the economic collapse.

World War I transformed the United States from a relatively small player on the international stage into a center of global finance. American industry had supported the Allied war effort, resulting in a massive influx of cash into the US economy. As the war interrupted existing global trade relationships, the United States stepped in as the main supplier of goods, including weapons and ammunition. These purchases left European countries deeply in debt to the United States.

After the war, the United States began a period of diplomatic isolation. It enacted and raised tariffs in 1921 and 1922 to bolster American industry and keep foreign products out.

In the 1920s (the “Roaring Twenties”) many American consumers, assuming economic prosperity would continue indefinitely, took on large amounts of personal debt, sometimes at extremely high interest rates. Factories depended on these consumers continuing to purchase their goods.

Finally, the stock market, based on Wall Street in New York City, was loosely regulated. There were few rules to ensure invested money was safe. Speculators began to deliberately manipulate stock prices, buying and selling in order to increase their returns. Only a small number of Americans purchased stock directly, most believing that the market values would continue to increase. Many investors, comfortable with debt, bought stocks “on the margin,” using a small personal investment to pay a portion of the actual share value while borrowing the rest from a bank or other lender. They assumed the stock price would rise and they would be able to repay the balance of the loan from their investment profits. This system worked well, until the stock decreased in value.

The Crash

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, stock prices began to fall on the New York Stock Exchange, losing 11% of their value in a single day. After some initial stabilization, news of the falling stock prices led lenders to call on investors to repay loans. A massive sell-off began, causing the market to lose even more ground and setting off a panic across the country. By mid-November, the value of the nation's stocks had fallen by 33%. Banks which had lent money to failed investors or businesses simply no longer had the cash on hand to pay their customers. The average citizen, frightened and pessimistic about his or her economic prospects, stopped buying non-essential goods; spending dropped by 20% in 1930. This, in turn, drove down demand for consumer goods and more businesses began to fail. Unemployment rates doubled. Individual households were bankrupted as banks and lenders called in outstanding loans. President Herbert Hoover directed his administration to reduce spending. He signed the protectionist Smoot-Hawley Tariff in June 1930, in an attempt to bolster American agriculture and consumer goods. It had the adverse effect of spurring other governments to enact retaliatory tariffs, decreasing the foreign market for American goods.

Impact on Immigration

The Great Depression also had a serious impact on an already xenophobic and exclusionary American immigration system.

As a result of the worsening Depression, President Herbert Hoover instructed the State Department to begin rigorously enforcing a “likely to become a public charge” (LPC) clause from a 1917 immigration law.

This clause was designed to exclude any immigrant who lacked the economic means to be self-sufficient and who could potentially become a financial burden on the state. By 1930, unemployment had reached 8.7%, and consular officials were instructed to more rigidly enforce the LPC clause. They were informed that “any alien wage earner without special means of support coming to the United States during the present period of depression is, therefore, likely to become a public charge,” and should be rejected for an immigration visa.

These regulations, forcing potential immigrants to prove they were financially stable and could support themselves indefinitely without getting a job, limited the number of applicants who qualified for immigration visas. In the 1930s, when the Nazis began stripping Jews of their financial holdings prior to allowing them to immigrate, many had trouble passing the rigorous financial qualifications for entry to America.

Throughout the 1930s, the majority of Americans opposed increasing immigration to the United States. Many cited economic concerns, fearing that immigrants would compete for jobs, which were scarce during the Depression.

The Global Great Depression

The United States was a central part of the international economic system, and its national economic disaster could not be contained. It spread across the globe. It hit particularly hard in Europe where multiple nations were indebted to the United States. During World War I, the Allies (Britain and France) had bought a great deal of military weapons and products using loans from the United States. When the United States called for those loans to be repaid to stabilize its own economy, it threw foreign economies into economic depression as well.

In Germany, depression hit in a different but no less powerful way. The new Weimar Republic had weathered a period of intense inflation in the 1920s due to reparations required by the Versailles Treaty. Rather than tax German citizens to pay the reparations, Germany borrowed millions of dollars from the United States and went further into debt. American demands for loan repayment had disastrous repercussions for an already fragile German economy, with banks failing and unemployment rising. As in the United States, the Weimar Republic decided to cut spending rather than increase it to spur the economy, further worsening the situation.

The Great Depression and the Rise of the Nazis

The Great Depression also played a role in the emergence of Adolf Hitler as a viable political leader in Germany. Deteriorating economic conditions in Germany in the 1930s created an angry, frightened, and financially struggling populace open to more extreme political systems, including fascism and communism.

Hitler had an audience for his antisemitic and anticommunist rhetoric that depicted Jews as causing the Depression. Fear and uncertainty about Germany’s future also led many Germans in search of the kind of stability that Hitler offered.

While the Great Depression (and German economic conditions in general) were not solely responsible for bringing Hitler to power, they helped create an environment in which he gained support.

Critical Thinking Questions

How did the Depression make it more difficult for refugees to reach the United States?

Why did economic instability contribute to the possibility of mass murder in Germany but not elsewhere?

How can economic instability be a warning sign for genocide and mass murder?

How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity in the world?