How did the United States government and American people respond to Nazism?

Consideration of American responses to Nazism during the 1930s and 1940s raises questions about the responsibility to intervene in response to persecution or genocide in another country. As soon as Hitler assumed power in 1933, Americans had access to information about Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews and other groups. Although some Americans protested Nazism, there was no sustained, nationwide effort in the United States to oppose the Nazi treatment of Jews. Even after the US entered World War II, the government did not make the rescue of Jews a major war aim.

Explore this question to learn about the factors and pressures that influenced America’s responses to Nazism.

See related articles for background information related to this discussion.

As soon as Hitler assumed power in 1933, Americans had access to information about Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews. Although some Americans protested Nazism, there was no sustained, nationwide effort in the United States to oppose the Nazi treatment of Jews. The Great Depression, combined with a commitment to neutrality and deeply-held prejudices against immigrants, shaped Americans’ willingness to aid Jewish refugees from Europe. Although the United States issued far fewer visas than it could have during this period, it did admit more refugees fleeing Europe than any other nation. In addition, individuals and private relief agencies took efforts to assist refugees.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, the government prioritized defending democracy. The government’s wartime aim was not the rescue of Jews. In the spring of 1945, Allied forces, including millions of Americans serving in uniform, ended the Holocaust by militarily defeating Nazi Germany and its Axis collaborators.

The United States in the 1920s

From the end of World War I in 1918 through the 1920s, the United States became an increasingly isolationist nation. It remained apart from the political affairs of other countries. The government decreased the size of its military and committed to a policy of neutrality. Congress voted against joining the League of Nations, signaling its reluctance to get the United States too involved in international affairs.

In 1924, the US Congress passed new immigration laws. These laws set limits on annual immigration to the United States. A quota system, organized by country of origin, gave preference to immigrants from northern and western Europe. Those from southern and eastern Europe, where the vast majority of Europe’s Jews lived, were at a disadvantage. These laws were based in part on widely accepted theories of “eugenic science” and beliefs about the hierarchy of racial and national groups. The United States did not have a substantive refugee policy during this period. Those fleeing persecution were subjected to the same procedures as other immigrants.

Racism and antisemitism were common in the United States. Segregation was often enforced by laws, customs, and violence. Laws limiting immigration both depended on and advanced this climate of prejudice, promoting the “ideal” American as white and Protestant.

In 1929, the stock market crashed, and the Great Depression began in the United States. The effects quickly spread to the rest of the world. Four years later, 25% of all workers (some 13 million Americans) were still unemployed. Many Americans lost their savings, homes, and possessions. Under President Herbert Hoover’s administration (1929–1933), immigration fell dramatically. Many Americans believed that immigrants would compete for the scarce employment opportunities. Economic devastation led many Americans to look inward, focusing on the domestic recovery of their families and community, rather than on international affairs.

Americans’ Response to Nazi Germany’s Persecution of Jews

After Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933, the new Nazi government immediately began to impose restrictive antisemitic laws throughout the country. American newspapers widely reported on Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews throughout the 1930s. In the spring of 1933, Americans in major cities attended anti-Nazi rallies and marches. Thousands throughout the country also signed petitions protesting Nazi attacks on Jews. Various Jewish organizations and labor unions tried to convince Americans to boycott German-made goods. In addition, some segments of the American public debated whether or not to boycott the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin. The Kristallnacht terror attack against Jews throughout Greater Germany in November 1938, which was front-page news in much of the United States for about three weeks, received universal condemnation.

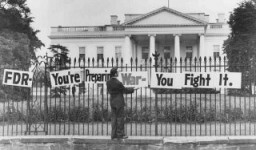

These efforts never led to a sustained, widespread anti-Nazi movement in the United States. Although the vast majority of Americans were aware of and disapproved of Nazism, many also believed that it was not the role of the US government to actively intervene in Germany’s treatment of its own citizens.

The Refugee Crisis

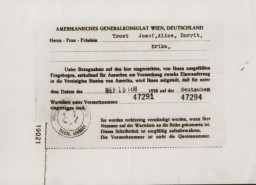

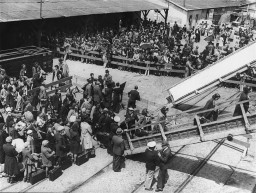

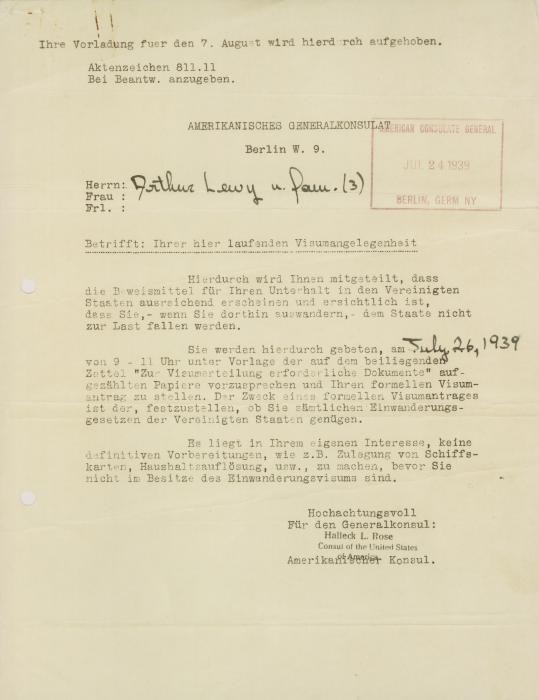

After Germany annexed Austria (Anschluss) in March 1938, hundreds of thousands of Jews joined the already long waiting list for immigration visas to the United States. The US immigration process was complicated and bureaucratic. It required applicants to submit extensive paperwork, some of which was expensive and difficult to obtain. Jews who wanted to immigrate to the United States had to compete for a finite number of visas and travel options, which became more limited and expensive after the war began. Most were unable to obtain visas because the quota system limited the number of immigrants who could enter the US during a given year. By 1939, more than 300,000 people were on the waiting list for a US immigration visa from Germany—a wait of more than 10 years, assuming that all available visas would be issued.

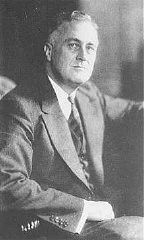

Despite many internal debates, neither President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration nor the US Congress adjusted immigration laws to aid the hundreds of thousands of refugees trying to flee Europe. On the contrary, there were many proposals in Congress during this era to further restrict immigration rather than to open the borders.

By 1938, Americans were well-aware of the refugee crisis caused by Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews and territorial expansion across Europe. Thousands of Americans signed affidavits sponsoring refugees who were attempting to immigrate to the United States, or donated money to relief agencies. Sympathetic journalists, celebrities, and spokespeople, such as Dorothy Thompson and Eleanor Roosevelt, tried to educate Americans about the positive contributions immigrants and refugees made in America.

Many private agencies—some Jewish and others non-Jewish, some long-established and others new—provided important leadership on behalf of refugees. These agencies helped refugees navigate the complicated immigration process. As part of their efforts, they explained paperwork, located financial sponsors, and purchased ship tickets. They also assisted with Americanization, employment, and housing for refugees who were fortunate enough to enter the United States. Jewish and non-Jewish organizations also provided food, clothing, and medicine for those still in Europe. These efforts, combined with significant yet limited government action, helped at least 111,000 Jewish refugees to reach the United States between 1938 and 1941.

Still, antisemitism increased in the United States throughout the 1930s. The majority of Americans did not support easing restrictive immigration laws to assist the hundreds of thousands of Jews attempting to flee Europe. For the most part, sympathy did not translate into action to aid the victims of Nazism. After the defeat of France in 1940, Americans grew even more concerned that immigrants, even Jewish refugees, posed national security threats. Anyone entering the United States was viewed as a potential Nazi spy, so US State Department officials decided to reject all visa applicants they believed might pose a security risk.

The Museum estimates that between 180,000 and 225,000 refugees fleeing Nazi persecution immigrated to the United States between 1933 and 1945. Although the US admitted more refugees than any other nation, thousands more could have been granted US immigration visas had the quotas been filled or expanded during this period.

Wartime Response

After World War II began in September 1939, most Americans hoped the United States would remain neutral. Many still believed that US intervention in World War I in 1917 had been a mistake and that the sacrifices required of Americans during times of war were not worth it. Over the next two years, however, amid a national debate between isolation and intervention, the US government and the American people slowly began to support the Allied powers. Yet the United States would not enter the war until it was attacked directly.

After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States declared war against Japan and entered World War II. Nazi Germany declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941. The US military was not prepared to fight a global war in 1941. During most of 1942, the US Navy battled in the Pacific, while ground troops trained for combat in North Africa and Europe. In November 1942, the State Department confirmed that Nazi Germany planned to murder all the Jews of Europe. Only a few weeks after the Allied invasion of North Africa on November 8, 1942, the American people opened their newspapers to read for the first time about Nazi Germany’s plan. The majority conceived of the fight against Nazism as a war to preserve democracy. Rescuing Jews was not a priority or a wartime aim for the United States.

A small minority did speak out on behalf of Europe’s Jews. As more information about the murder of Jews reached Americans throughout 1943, some organizations, like Peter Bergson’s Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe, organized rallies, marches, and placed full-page newspaper ads calling on the Roosevelt administration to formulate a rescue plan. They announced to the American people that the Nazi regime and its collaborators had already murdered over two million Jews. (Historians now estimate that more than five million Jews had been murdered by the end of 1943.)

In January 1944, US Treasury Department staff discovered that the State Department had delayed humanitarian aid from reaching Europe and had blocked information about the murder of Jews from reaching the American people. These Treasury staff members persuaded President Roosevelt to establish a War Refugee Board. The War Refugee Board was tasked with carrying out relief and rescue plans, as long as these plans did not impede the war effort. The Board succeeded in opening a refugee camp in Oswego, New York. It also sent Swedish businessman Raoul Wallenberg to Budapest to protect Jews there. The Board ultimately saved tens of thousands of lives and assisted hundreds of thousands more in the last year and a half of the war.

The Holocaust ended in the spring of 1945 after Allied forces, including millions of Americans who served, defeated Nazi Germany and its Axis collaborators and liberated the still-extant concentration camps.

Postwar US Response

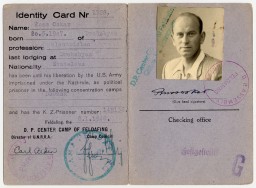

In the months after the war ended, the Allied military command opened displaced persons camps to house the millions of civilians displaced by the war, including newly liberated Jewish survivors and forced laborers. In the summer of 1945, President Harry S. Truman sent Earl Harrison, an American lawyer, to tour some of the displaced persons (DP) camps in Europe. Harrison submitted a troubling report about conditions in these DP camps. He told President Truman, “We appear to be treating the Jews as the Nazis treated them except we do not exterminate them.” Harrison’s report led to improvements in the administration of these camps. Resettling these refugees was neither quick nor easy. Some DP camps remained open well into the 1950s.

In the aftermath of the war, Allied forces also administered war crimes trials, attempting to bring the perpetrators of Nazi Germany’s crimes to justice. However, in some cases, the United States proved willing to overlook individuals’ collaboration with the Nazi regime if they could provide scientific knowledge or Soviet intelligence to the US government, which was entering the Cold War.

The United States did not immediately open its doors to Holocaust survivors. The Displaced Persons Act in 1948 eventually allowed about 400,000 displaced persons to enter the United States, though the majority were not Jewish. The Museum estimates that approximately 80,000 Jewish survivors immigrated to the United States between 1945 and 1952.

Critical Thinking Questions

What were the main reasons for US resistance to immigration and rescue before 1939? Did these factors change during World War II?

What pressures and motivations at home and abroad drive support or resistance to immigration, or even refugee rescue, in your country?

How can knowledge of the events in Germany and Europe before the Nazis came to power help citizens today respond to threats of genocide and mass atrocity?