Chełmno (Kulmhof) Killing Center

The Chełmno (Kulmhof) killing center was one of five killing centers that Nazi Germany created as part of the “Final Solution”— the Nazi plan to murder Europe’s Jews. Chełmno was the first camp where the Nazis murdered Jewish people in gas chambers using poisonous gas. In total, the Nazis murdered at least 152,000 Jews and 4,300 Roma at Chełmno.

Key Facts

-

1

The gas chambers at the Chełmno killing center were located in the cargo area of large vans. The victims were murdered with carbon monoxide gas.

-

2

The Nazis operated the Chełmno killing center in two periods. The first period was December 1941–April 1943. The second period was June 1944–January 1945.

-

3

Only seven Jewish men are known to have escaped from Chełmno. Several of them spoke, wrote, or testified about what they witnessed.

The Chełmno (in German, Kulmhof) killing center was one of five killing centers that Nazi Germany created as part of the “Final Solution.” The “Final Solution” was the Nazi plan to murder Europe’s Jews. Chełmno (Kulmhof) was the first camp to which the Nazis transported Jewish people in order to murder them in gas chambers. Nazi authorities specifically established Chełmno to murder most of the Jewish population of the Warthegau, a part of German-occupied Poland.

The Nazis operated the Chełmno killing center in two periods. The first period was from December 1941 until April 1943. The overwhelming majority of victims were murdered in this first period. The second period lasted from June 1944 to January 1945.

In total, Nazi Germany murdered at least 156,300 people at Chełmno (Kulmhof). The victims of Chełmno included at least 152,000 Jews; about 4,300 Roma; and an unknown number of non-Jewish (ethnic) Poles and Soviet POWs. Most of the people killed at Chełmno were Polish Jews from the Warthegau region, including tens of thousands of Jews from the city of Łódź.

The mass murder of Jews at Chełmno (Kulmhof) began in December 1941. The first transport of Jews arrived at Chełmno on December 7. It included approximately 700 Jewish men, women, and children from the nearby town of Koło. On the following day, December 8, the Nazis murdered all of these people in gas chambers.

The start of mass murder at Chełmno in December 1941 came at a critical moment in the Nazis’ implementation of the “Final Solution.” By this time, the Nazis and their helpers had murdered hundreds of thousands of Jewish people in mass shooting operations in occupied eastern Europe. The Nazis had also begun to use poisonous gas to murder Jewish people in mobile gas chambers installed in vans that traveled from place to place.

The mass gassings at Chełmno marked an important step in the “Final Solution.” Over the next three years, the Nazis would murder approximately 2.7 million Jews at killing centers. The 700 Jewish people murdered at Chełmno on December 8 were the first of these victims.

Prelude to Mass Murder at Chełmno (Kulmhof): The Holocaust in the Warthegau

Nazi officials established the Chełmno killing center in fall 1941. The purpose of the killing center was to murder Jewish people living in the Warthegau. The Warthegau was a part of German-occupied Poland that the Nazis hoped to Germanize. Beginning with the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, German authorities treated Jews in this region with increasing brutality. The creation of Chełmno was a radical and deadly escalation of these Nazi anti-Jewish policies.

What was the Warthegau?

The Warthegau (formally, Reichsgau Wartheland) was a Nazi administrative unit governing part of German-occupied Poland during World War II. It included the Polish cities of Poznań (in German, Posen); Łódź (renamed Litzmannstadt by the Germans); and Inowrocław (in German, Hohensalza). In 1939, this area was home to about five million people, including about 4.2 million non-Jewish (ethnic) Poles; some 400,000 Jews; and 325,000 ethnic Germans.

The Nazi Party leader (Gauleiter) and Governor (Reichsstatthalter) of the Warthegau was Arthur Greiser. As such, Greiser was in charge of the administration of the entire Warthegau. He answered directly to Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. The Higher SS and Police Leader (Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer, or HSSPF) for the Warthegau was SS officer Wilhelm Koppe. Koppe was in charge of all SS and police forces in the Warthegau. He reported to Heinrich Himmler. Both Greiser and Koppe were key players in the persecution of Jews in the Warthegau and in the mass murder of Jews at Chełmno.

As part of the Nazis’ desire to acquire Lebensraum (“living space”), Greiser and Koppe were determined to Germanize the Warthegau, which Nazi Germany had annexed to the Greater German Reich. Germanizing the Warthegau meant ethnically cleansing the territory by deporting, imprisoning, and killing Polish and Jewish people whose families had lived there for centuries. With much of the local population displaced, the Nazis moved ethnic Germans from eastern Europe into homes they had stolen from Poles and Jews in the region.

Anti-Jewish Policies in the Warthegau, 1939–1941

Most of the Warthegau’s Jewish population lived in and around the large industrial city of Łódź, where Jews made up about a third of the population. In Łódź, many Jewish people were employed in the city’s textile industry and participated in a lively Jewish cultural scene.

Almost immediately after the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Nazis implemented anti-Jewish policies and persecuted Jews. They were particularly harsh in Łódź, where they confiscated Jewish-owned homes and businesses and put in place strict anti-Jewish measures.

In Łódź and throughout the Warthegau, German authorities forced Jewish people to wear Star of David badges marking them as Jews beginning in late 1939. This was one of the earliest instances of this practice during the Holocaust. In response to the Nazis’ antisemitic policies and violence, many Jews fled the region.

Beginning in late 1939, German authorities deported thousands of Jews east, from the Warthegau to the General Government. The General Government was the neighboring administrative unit of German-occupied Poland. The Nazi German authorities also required Jews to perform forced labor, including construction work. They imprisoned tens of thousands of Jewish people in ghettos located in villages, towns, and cities in the region. By far the largest was the Łódź ghetto, established in the spring of 1940. The Łódź ghetto was administered by Hans Biebow. Biebow would become intimately involved in the mass murder of Jews at Chełmno.

The Decision to Murder Jews in the Warthegau

In the summer or early fall of 1941, on Arthur Greiser’s initiative, German authorities decided to murder all Jews in the Warthegau whom the Nazis deemed incapable of work. They planned to keep some Jewish people alive to carry out forced labor in the Łódź ghetto. Evidence indicates that sometime between July and September 1941, Greiser received permission from Hitler to carry out this plan.

Sonderkommando Lange and Mass Murder Using a Gas Van

In early fall 1941, SS officer Herbert Lange was tasked with carrying out the mass murder of most of the Warthegau’s Jewish population. Lange was chosen because he was in charge of a specialized SS killing unit with a gas van. This mobile gas chamber was a large van whose back storage area had been converted into an airtight gas chamber to murder people with poisonous carbon monoxide gas. Lange’s unit was called Sonderkommando Lange (literally, “special commando Lange”). Starting in the fall of 1939 and into 1941, Sonderkommando Lange traveled throughout the Warthegau, murdering patients in Polish psychiatric facilities and other institutions. By the time Lange was assigned to murder Jews, the Sonderkommando Lange had already murdered more than 7,500 people.

In late September 1941, Lange’s unit began to murder Jews. They traveled to towns in the Warthegau and carried out massacres of Jews from the Konin district in their gas van.

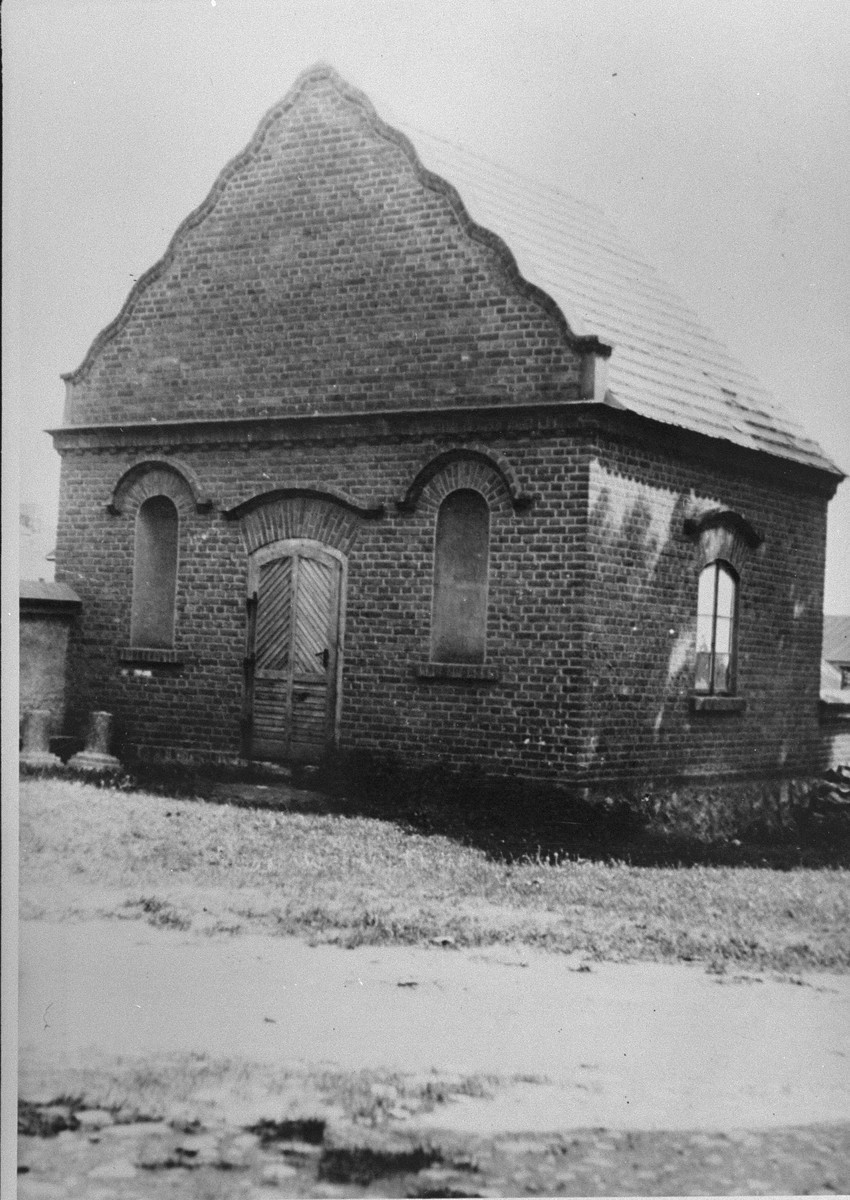

Establishment of the Chełmno (Kulmhof) Killing Center

By November 1941, Sonderkommando Lange had decided that rather than traveling to communities to carry out massacres, they would transport Jewish people to a killing center and murder them there. Sonderkommando Lange established this killing center in the Polish village of Chełmno nad Nerem (Kulmhof an der Nehr in German). This village was about 40 miles northwest of Łódź. Though somewhat isolated, it was still accessible by rail. At first, the killing center was still primarily referred to as Sonderkommando Lange. Later, it became known as Sonderkommando Kulmhof.

Nazi Officials and Other Staff at Chełmno (Kulmhof)

SS and police officials subordinate to HSSPF Wilhelm Koppe were responsible for killing operations at Chełmno. Initially, SS officer Herbert Lange served as the head of Sonderkommando Lange and thus as the commandant of the Chełmno killing center. In March 1942, Lange was transferred to the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin. SS officer Hans Bothmann replaced him as commandant. At this time, the Sonderkommando became known as Sonderkommando Bothmann or Sonderkommando Kulmhof.

Members of the German Sonderkommando

The members of the German Sonderkommando included a small group (between 10 and 15 men) of Security Police officials, most of whom were also members of the SS and the SD. The Sonderkommando also included a unit of uniformed German policemen. This uniformed police unit was called the Polizeiwachtkommando. Its members came to Chełmno from Łódź. The uniformed policemen served as guards. They also rounded up Jewish victims from surrounding ghettos and drove Jewish victims to the killing center by truck.

The Polish Prisoners

Eight Polish prisoners were also forced to work as gravediggers and in other capacities at the Chełmno killing center. They had been forced to work as gravediggers for Sonderkommando Lange since late 1939. At Chełmno, these Poles were neither fully prisoners (they had some freedom of movement and contact with outsiders) nor fully employees (they were not paid, and they were not free to leave). The level and nature of coercion involved in their participation is unclear. Postwar accounts from two of these prisoners provide important evidence of the events that took place at Chełmno. One of them, Henryk Mania, was later tried and convicted for his participation in Nazi crimes.

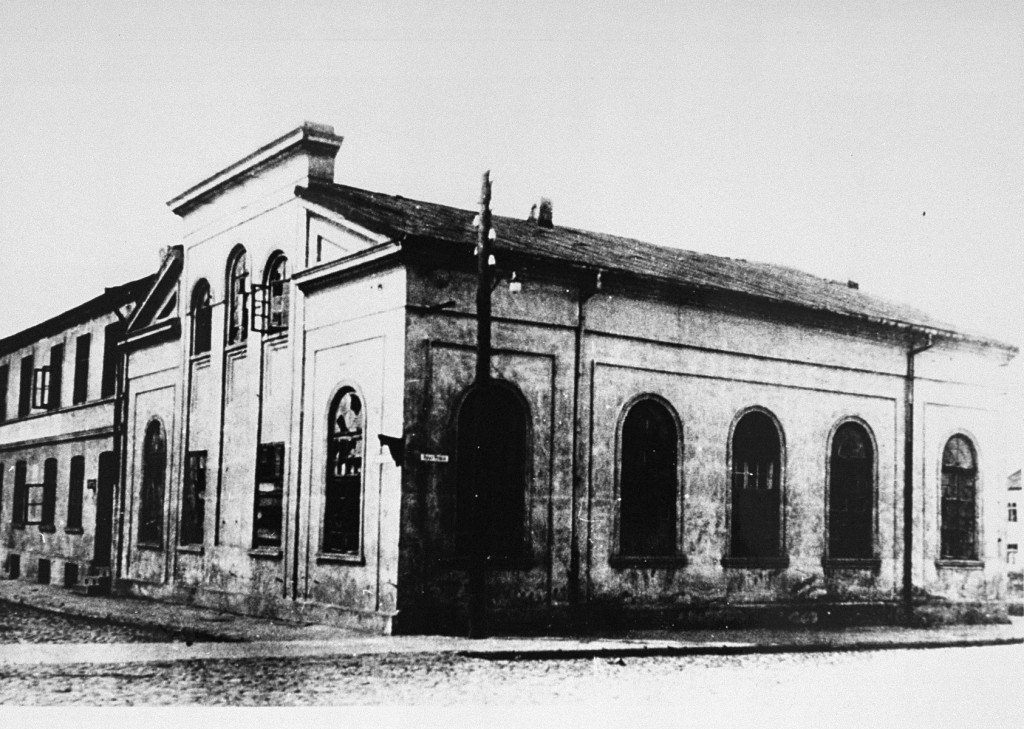

Layout of the Chełmno (Kulmhof) Killing Center

To create the Chełmno killing center, SS officer Lange and his staff requisitioned a number of buildings in the village of Chełmno. These buildings included a run-down manor house that had been converted into an apartment building before the war; the village’s community administration building (gmina); the village fire station; a church; and several private homes. The Germans also confiscated a forested area along the road north of the village. Other than the manor house, the other buildings were mostly used for housing and feeding the SS and police staff and guards.

The Chełmno killing center consisted of two main parts: the manor house (located in the village of Chełmno) and a large clearing in the Rzuchów forest.

Converting the Manor House

After the SS requisitioned the manor house and surrounding grounds, they modified it to use as part of the killing center. A high wooden fence surrounded the building and the grounds on three sides to keep what happened there from view. The back side of the property was hidden from view by the natural terrain. On the main level of the house, the Nazi staff set up rooms where victims would be forced to undress and relinquish their remaining valuables. In the basement, the Nazis created workshops and living quarters for a small number of prisoners. They also installed a walled ramp that the killers used to force Jewish prisoners into the gas vans.

The Forest Area

The Rzuchów forest, located approximately 2.5 miles (about 4 km) northwest of the village of Chełmno, became the burial site for those murdered in gas vans at the manor house. The area was commonly called the forest camp. It included a large cleared area, surrounded by trees. Initially, there were multiple mass graves in the forest. Later, when mass burial was no longer feasible, the SS constructed various types of burning pits and crematoria in the forest camp.

The Killing Process at Chełmno (Kulmhof) in the First Period, 1941–1943

At Chełmno, the Nazis dehumanized their victims through deception and terror. Almost all Jewish people sent to Chełmno were immediately murdered in a dehumanizing killing process.

In all known cases, Nazi officials brought Jewish prisoners to the grounds of the Chełmno killing center in trucks. Guarded by members of the German Sonderkommando, the victims disembarked in the courtyard of the manor house. Then, an SS or police official would give a deceptive “welcome speech.” The official would lie, telling the Jews that they were at a transit camp and would be transferred elsewhere for forced labor. The official then instructed the Jewish prisoners to enter the manor house in order to bathe and be disinfected. This speech, as well as the pleasant and professional manner in which it was delivered, was intended to mislead victims and keep them calm.

Once inside the manor house, Jews at Chełmno were forced to undress and hand over their valuables. Unlike at other killing centers, the victims were not separated by gender. Telling them that they would be taken to bathe, Sonderkommando personnel then led the naked men, women, and children to the basement. There, the perpetrators forced the victims to walk up a walled wooden ramp into the back of a large paneled van. When the back of the van was so full that the people inside could barely move, the doors were closed and sealed. Then, a German official attached a tube to the van’s exhaust pipe and the driver started the van’s engine. The engine pumped exhaust with a high percentage of deadly carbon monoxide gas into the back of the van, killing the victims by asphyxiation. Witnesses estimate that the killing process took about 60–90 minutes from welcome speech to death.

After the victims were dead, the tube was detached from the exhaust pipe. A member of the German Sonderkommando served as the van driver. He drove the van to the forest camp to dispose of the corpses.

During the killing center’s existence, there were several gas vans in operation at Chełmno.

Disposing of the Bodies at Chełmno (Kulmhof)

After victims were murdered in the gas vans at the manor house, a van driver transported the corpses to a mass grave in the forest camp. At the forest camp, Jewish prisoners were forced to remove bodies from the gas chamber at the back of the van. The Polish prisoners searched the corpses for jewelry and valuables. The German Sonderkommando men shot any victims who had survived the gassing.

For the first six months of Chełmno’s operation, the bodies of the victims were buried in mass graves. But this burial method created problems. Not only did the graves fill quickly, but the stench of decomposing bodies spread through the surrounding area, including nearby villages.

In summer 1942, the Sonderkommando temporarily stopped killing operations at Chełmno to figure out what to do with the decomposing corpses. SS officer Paul Blobel came to Chełmno to assist in this process. Blobel was the former commander of Sonderkommando 4a, a part of killing unit Einsatzgruppe C. Blobel’s unit had perpetrated the massacre of nearly 34,000 Jews at Babyn Yar. Subsequently, Blobel had been put in charge of a new, top secret operation called Sonderaktion 1005 (literally, “special action 1005”). His new mission was to hide evidence of Nazi crimes by exhuming mass graves and destroying the human remains.

At Chełmno, in the summer of 1942, Blobel experimented with various methods of disposing of corpses, including the use of explosives. Eventually, under Blobel’s supervision, the German authorities at Chełmno built several different types of crematoria to burn the bodies.

Beginning in summer 1942, Jewish prisoners in the forest camp were forced to burn the bodies in these crematoria. That summer, the German Sonderkommando acquired a bone grinding machine. They used this machine at Chełmno to grind any bone fragments remaining in the ashes. At first, the prisoners buried the ashes in the ground. Later, they sprinkled the ashes in the forest or dumped them into a nearby river.

Victims Murdered at Chełmno (Kulmhof) in the First Period, 1941–1943

The Nazis operated the Chełmno killing center in two periods. The first period was from December 1941 until April 1943. Most of Chełmno’s victims were murdered during this time. The overwhelming majority of the Jewish men, women, and children killed at Chełmno were Polish Jews from the Warthegau region.

The First Victims of Chełmno, December 1941

The earliest victims of Chełmno were Jews brought to the killing center by trucks from nearby towns and villages in December 1941. These first victims were Jews from the town of Koło and the villages of Dąbie and Dobra. Among the victims were Shlomo Gruenfeld from Dąbie and Ester and Pola Jakubowicz from Dobra.

Murder of Roma from the Łódź Ghetto, January 1942

In early January 1942, the Nazis murdered several transports of Romani people (derogatorily called “Gypsies”) at the Chełmno killing center. These were Roma whom Nazi German authorities had deported from Austria to the Łódź ghetto in November 1941. The approximately 5,000 Romani people were imprisoned in a separate section of the ghetto. Very little had been prepared for their arrival, and they lacked basic facilities and supplies. Typhus spread quickly. Hundreds of Romani people died in just a few weeks. In early January, German authorities murdered the remaining Romani prisoners, about 4,300 people, in the Chełmno killing center.

Transports of Jews from the Łódź Ghetto, January–September 1942

Beginning on January 16, 1942, Nazi authorities transported tens of thousands of Jews from the Łódź ghetto to the Chełmno killing center. Hans Biebow (the head of the German ghetto administration) and other German authorities intended to use the transports to transform the Łódź ghetto into a working ghetto. Anyone deemed incapable of work would be murdered at Chełmno. The uncertainty and loss wrought by these transports devastated and destabilized the ghetto population.

Transports from the ghetto occurred in several waves. A committee appointed by Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Jewish Council, determined who from the ghetto would be chosen. By April 2, German authorities transported more than 44,000 Jewish people from the ghetto to Chełmno. Among them were the most marginalized members of the ghetto community: the poor, the unemployed, refugees from outside of Łódź, and people who had been caught breaking ghetto rules.

In May 1942, authorities targeted a different subset of the ghetto population: Jews who had been deported to the Łódź ghetto in late 1941 from Vienna, Prague, Luxembourg, and Berlin and other German cities. In May 1942, German authorities transported almost 11,000 of this group to Chełmno, where they were murdered. Many of them were elderly or ill. Among the victims were Ignatz and Regine Auerbach, who were both in their sixties. The Auerbachs had been deported from Vienna to the Łódź ghetto in October 1941.

After a three month pause, transports from the Łódź ghetto to Chełmno resumed in September 1942. That month, more than 15,000 Jews—primarily children, the ill, and the elderly— were taken from the ghetto and murdered at Chełmno. Many of the children had been forcibly separated from their families after Rumkowski called on the ghetto population to sacrifice their children. Among the murdered children were Mosze Lapides and his younger sister Miriam.

In total, German officials murdered more than 70,000 Jewish men, women, and children from the Łódź ghetto at Chełmno in 1942.

Transports from Other Towns and Villages in the Warthegau, January–September 1942

In addition to the deportations from the Łódź ghetto, the SS and police also deported Jews from towns throughout the Warthegau to the Chełmno killing center in 1942. This included Jewish communities from ghettos in the towns of Kutno, Grabów, Pabianice, Brzeziny, Łask, Bełchatów, and elsewhere.

In these towns, Nazi officials usually sorted the ghetto population into two groups. They chose some Jews for forced labor in the Łódź ghetto, while others were destined for Chełmno. Witnesses describe the brutality of the roundups in these ghettos. Nazi officials, often led by Hans Biebow, terrorized and killed people in the process. In many cases, the perpetrators imprisoned Jewish people for days in a church, school, or synagogue. They deprived the victims of food or water. Finally, they loaded the weakened and terrorized victims onto trucks. They drove these trucks directly to the Chełmno killing center, where the victims were murdered.

Among the victims from these ghettos were Jonah and Pesa Wasilkowski and two of their children, Cela and Josef. The family was taken from the Ozorków ghetto and murdered at Chełmno in spring 1942.

Unknown Victims

Evidence indicates there are unknown or unconfirmed victims of Chełmno who remain uncounted. Witness accounts describe a transport of Jewish people speaking French. The origin of this transport is unknown. It is also possible that another transport from the Łódź ghetto arrived at Chełmno in February 1943. Additionally, there are witness accounts describing the murder of Soviet POWs, Polish soldiers, and elderly Poles from a nursing home. It is also likely that in the fall of 1942, the Nazis murdered Czech children whom they kidnapped from the town of Lidice.

Jewish Prisoner Forced Laborers in Chełmno (Kulmhof)

At Chełmno, a small number of Jewish prisoners were selected to carry out forced labor in the killing center. They were responsible for sorting the belongings of the victims and disposing of corpses. A small number of skilled prisoners were forced to produce or repair goods for the German Sonderkommando. After two prisoners escaped in January 1942, Jewish prisoners were required to wear leg shackles while carrying out their gruesome tasks. The German Sonderkommando men regularly shot or killed prisoners for minor infractions and for their own amusement.

Forced labor at Chełmno was all the more brutal and traumatic because of the intimacy of the violence. The Nazis established the Chełmno killing center to murder Jews from a relatively small region. This meant that many of the forced laborers witnessed the annihilation of their families and communities before being murdered themselves. The few Jewish witnesses who survived described the devastation they felt when they and other Jewish prisoners saw the bodies or belongings of their murdered family members. They also recounted that the forced laborers regularly recited Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead.

How did I know my mother arrived at Chełmno? There were many handbags, a mountain of handbags. Once, I found a handbag with my mother's pictures and all her documents.

Szymon Srebrnik, Chełmno survivor

That day (Tuesday), the bodies of my wife and my two children—a seven-year-old boy and a four-year-old girl—were thrown out of the third van load that arrived in the Chełmno forest. I lay down next to the body of my wife. I wanted them to shoot me.

Michał Podchlebnik, Chełmno survivor

Closing Chełmno (Kulmhof), September 1942–April 1943

In fall 1942, the German authorities in the Warthegau stopped the systematic deportation of Jews to Chełmno. At this point, the only sizable Jewish population still alive in the Warthegau was in the Łódź ghetto. There, tens of thousands of Jewish people, mostly from Łódź and the other parts of the Warthegau, were kept alive to work in factories and workshops that served the German war effort.

Because the deportations had stopped, the German Sonderkommando began to dismantle Chełmno. In fall 1942 and spring 1943, they attempted to cover up the killing center’s existence. They forced the remaining Jewish prisoners to continue to dispose of the corpses. They also tried to cover up the gravesites by planting trees in the forest. In spring 1943, the German Sonderkommando members murdered all remaining Jewish forced laborers. On April 7, 1943, they attempted to blow up the manor house. The last Nazi German officials left the village of Chełmno on April 11. A small guard force remained behind to try to ensure the secrecy of the forest camp.

The Second Period: Reopening Chełmno (Kulmhof) and Destroying the Łódź Ghetto, 1944

In early 1944, SS and police officials decided to reopen the Chełmno killing center in order to murder the remaining inhabitants of the Łódź ghetto. The members of SS Sonderkommando Bothmann were recalled from their other duties. By March 1944, the Sonderkommando returned to the village of Chełmno. Because they had destroyed the killing center’s infrastructure in spring 1943, they had to rebuild and restructure the camp. This included building undressing barracks (because they had blown up the manor house) and building new crematoria.

Transports from the Łódź ghetto to the reopened Chełmno killing center resumed on June 23, 1944. The Jews in the ghetto were lied to and asked to volunteer for special labor service outside of the ghetto. From June 23 to July 14, over 7,000 people were taken from the ghetto to Chełmno in ten transports. Almost all of them were murdered.

In this second period, the Nazi authorities altered the arrival process. In 1944, Jews from the Łódź ghetto arrived by rail in the town of Chełmno. They were then taken to the village church, where they were forced to stay overnight. In the morning, they were taken by truck to the forest camp, where they were murdered by poisonous gas in gas vans. Then, Jewish prisoners were forced to remove the corpses from the vans and burn the bodies in the newly rebuilt crematoria.

The End of Chełmno (Kulmhof), 1944–1945

In July 1944, the transports from Łódź to Chełmno were halted for reasons that are not entirely clear. In August 1944, when the destruction of the Łódź ghetto resumed, the remaining Jewish prisoners were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In August 1944, the German Sonderkommando once again began slowly dismantling the Chełmno killing center. On the night of January 17, 1945, they shot the remaining Jewish prisoners. A few prisoners attacked the guards and attempted to escape. The next day, the Germans abandoned what was left of the killing center. Soviet forces arrived shortly afterwards.

In the years that followed, several Nazi perpetrators responsible for events at Chełmno were executed for their crimes. This included Hans Biebow (1947), Arthur Greiser (1946), and Paul Blobel (1951). The two commandants of Chełmno, Herbert Lange and Hans Bothmann, were not tried. Lange died during the Battle of Berlin. Bothmann killed himself while in British custody. Later, in the 1960s, several members of the German Sonderkommando were convicted and sentenced to prison terms.

Knowledge of the Chełmno (Kulmhof) Killing Center

Despite its significance, Chełmno is one of the lesser-known Holocaust sites. This is, in part, because Nazi German authorities attempted to keep Chełmno a secret. They used various forms of deception to cover up the existence of the killing center. They also attempted to erase evidence of their crimes by destroying paperwork, demolishing buildings, and burning the bodies of their victims. They hoped to erase the existence of the camp and the memory of the Jewish people murdered there. Despite their efforts, the Nazi German crimes committed at the Chełmno killing center did not stay a secret.

Escapees from Chełmno (Kulmhof) as a Source of Information

An important source of information about Chełmno comes from escapees who had been in forced labor. At least seven Jewish men escaped from Chełmno. Five of them escaped in 1942, during the first period of the killing center’s operation. Abram Rój, Michał (Mordechai) Podchlebnik, and Szlama ber Winer escaped in January 1942. Yerachmiel Widawski and Yitzhak Justmann escaped later that year. Two more men, Mieczysław Żurawski and Szymon Srebrnik, both escaped Chełmno on the night of January 17, 1945, during the camp’s final liquidation.

The men who escaped from Chełmno in 1942 tried to warn Jews in the neighboring communities about the mass murder that was taking place at the killing center. News had already made its way to the Grabów ghetto and the Łódź ghetto in January 1942, shortly after mass murder at Chełmno began.

Szlama ber Winer’s account of what he witnessed in Chełmno is particularly noteworthy. Within weeks of his escape, Winer made his way to the Warsaw ghetto. There, he gave an account of his experiences to a Jewish underground movement called Oneg Shabbat. This group wrote down Winer’s account in February 1942 and incorporated his information in a March 1942 report. They smuggled this report to the Polish government-in-exile in London. On July 2, 1942, it appeared in a New York Times article published on page six. Winer was later murdered at the Belzec killing center. Winer’s firsthand account and the report based on it were buried in the Oneg Shabbat archive and recovered after the war.

Postwar Investigations, Testimonies, and Trials

Immediately after the Soviets arrived in January 1945, investigations into the events at Chełmno were opened. The Soviets created a brief report. Then, the Main Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland and the Central Jewish Historical Commission began investigating events at Chełmno. A delegation from these commissions visited the site in May 1945. The following month, Judge Władysław Bednarz was appointed by the Polish Ministry of Justice to conduct an official investigation into crimes committed at Chełmno. As part of his investigation, Bednarz collected testimonies from three of the survivors, as well as local villagers. He also directed some early excavation work and the exhumation of graves. Judge Bednarz’s findings were published in 1946.

In 1961, two Chełmno survivors, Srebrnik and Podchlebnik, testified at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel, which was televised internationally. They described for a worldwide audience what they had witnessed and how their families and communities had been murdered. Then, in 1962–1963, 12 members of the German Sonderkommando were tried in West Germany. Depositions from survivors, perpetrators, and witnesses gathered for this trial also provided important information.

Number of Victims of Chełmno (Kulmhof)

Because the perpetrators likely destroyed most of the paperwork related to Chełmno, the exact number of victims of the killing center is unknown. However, based on surviving German records, scholars and courts have calculated that at least 152,000 Jews and 4,300 Romani people were murdered at Chełmno. An unknown number of non-Jewish (ethnic) Poles and Soviet POWs were also killed there. The records include the Korherr report, records from the Łódź ghetto, and other surviving documents. But, based on demographic data from ghettos in the Warthegau and witness testimony, it is likely that the number of Jewish victims was slightly higher. The number of Jewish victims of Chełmno was likely between 152,000 and 200,000.

In total, Nazi Germany murdered at least 156,300 people at Chełmno (Kulmhof). This includes at least 152,000 Jews and about 4,300 Roma. The overwhelming majority of people killed at Chełmno were Polish Jews from the Warthegau.

Critical Thinking Questions

Did the outside world have any knowledge about the killing centers? If so, what actions were taken by other countries and their officials?

What choices do other countries have in the face of mistreatment of civilians?