The International League Against Anti-Semitism in North Africa

Generally speaking, anti-Jewish sentiments or violence in North Africa tended to emanate from the Christian, European settler colonial population rather than the local Muslim one. The roots of European antisemitism reached back to the nineteenth century. After the French state extended French citizenship to Algerian Jews (with the Crémieux Decree of 1870), antisemitic writers like the pseudonymous Daniel Kimon expressed hatred of Jews and Muslims, groups that he felt posed a biological danger to Christian nations, Aryan societies, and France in particular. The works of antisemitic French writers Edouard Drumont and Ernest Renan circulated widely in French Algeria at this time, and their ideas were repurposed in newspapers in Algiers, Oran, and Constantine. At the same time, antisemitic thinkers like Max Régis (né Massimiliano Régis Milano) gained power in universities and the public administration in Algeria.

During the 1920s and 1930s, antisemitic political associations reemerged to protest what they perceived as the exploitation of Algeria by Algerian Jews. Newspapers such as La Croix de Feu, Le Front Paysan, and the Unions Latines launched campaigns blaming Jews for the economic turbulence of the era. These sentiments led to outbreaks of violence between Christians and Jews (as well as between Muslims and Jews) in Algeria. In the city of Constantine alone, 59 such episodes could be counted between 1929 and 1934. Jewish responses to this violence included the establishment of Le Comité d’Union Sémite Universelle, an organization based in Algiers and other Algerian cities, which aimed to counter antisemitic propaganda and advocate for a shared Muslim-Jewish administration of Palestine. Echoing the goals of Le Comité d’Union Sémite Universelle, Muhammed al-Kholti, a moderate Moroccan nationalist leader, wrote a 1933 column calling for an entente between Muslims and Jews.

It was within this climate—and in the direct aftermath of the violence that broke out in Hebron and Jerusalem in 1929—that the International League Against Anti-Semitism (LICA) was founded under the leadership of Bernard Lecache, the son of Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe. The organization’s first meeting, in Paris, was dedicated to the subject of ‘Peace in Palestine and Jewish-Arab Reconciliation.’

Lecache believed that a successful Jewish–Muslim entente was achievable through the fostering of friendly debate between Muslims and Jews. Though at the outset the organization focused on the question of Palestine, in time it became far more engaged with building Muslim-Jewish partnerships to combat Nazism, racism, and antisemitism in the Mediterranean.

One of the early mandates of LICA was to quell the tension emerging between Jews and Muslims in North African villages in response to visitations by Zionist envoys of the Jewish National Fund (KKL) and the Palestine Foundation Fund (KH). To explore this dynamic, Bernard Lecache was sent by LICA to engage in a mission to North Africa with his wife Denise Montrobert, daughter of the French socialist journalist Caroline Rémy de Guebhard. Lecache’s tour put him in contact with LICA branches across North Africa, and led to the establishment of more such branches (in the Tunisian cities of Sousse [Susa], Bizerte Nabeul [Benzart], Ferryville [Menzel Bourguiba], and La Goulette [Port of Tunis]) and of women’s sections of the organization.

Certain Muslim reformers were receptive to Lecache’s message, among them Cheikh Ben Badis, Mohammed Salah Bendjelloul, and Cheikh El-Okbi. In 1939, Abder-Rahmane Fitrawe published Le racisme et l’Islam, a booklet included short excerpts from Mein Kampf in Arabic translation, which sought to illustrate the threat of Nazism and Fascism in part by arguing that the philosophies went against the teachings of Islam. Some of these Muslim intellectuals were criticized for allying with Jewish leaders and calling for Muslim-Jewish collaboration.

In the face of these efforts, Nazi Germany opened an office in Melilla in 1937 and founded the International Anti-Jewish League in Tangier. Adolf Langenheim and Johannes Bernhardt, Nazi representatives in Spanish Morocco (under the control of Francisco Franco by June 1940), launched a massive anti-Jewish campaign via Servicio Mundial, a publication which included translations and summaries of European antisemitic literature. Antisemitic leaflets in Arabic and excerpts of Hitler’s speeches were also widely distributed among Muslim populations: this hateful propaganda blamed Jews for starting the Spanish Civil War and claimed that Jewish global capitalists would enslave Muslims if the Communists should win World War II.

LICA was born of French-Jewish concerns that fascist and antisemitic ideas would spread from Europe to indigenous populations in France’s colonies. Because of this rising concern, the organization sought a Jewish-Muslim partnership in order to combat common racist and antisemitic language and action prevalent in the 1930s.

Critical Thinking Questions

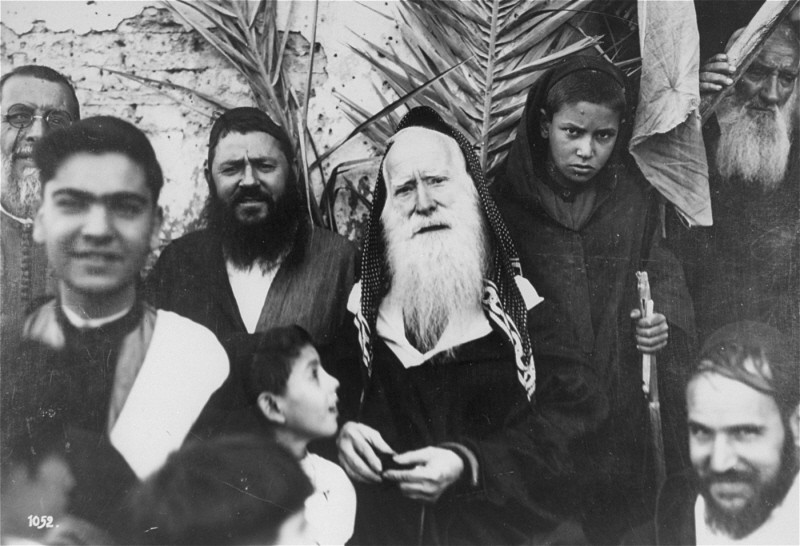

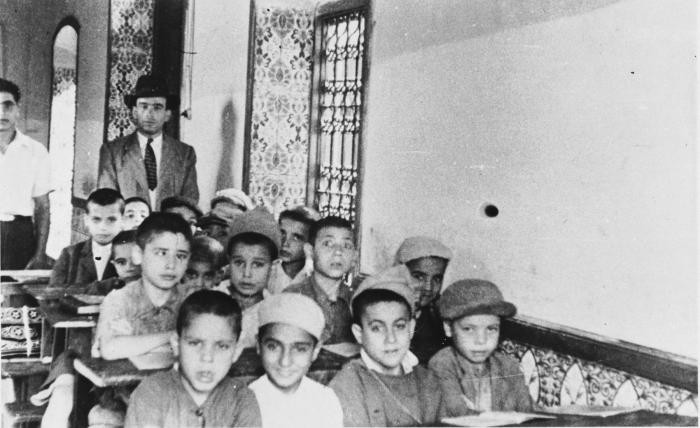

- Learn about the diverse Jewish communities of North Africa before World War II.

- What was the relationship between German expansion and the fate of Jews in North Africa?

- Explore recent scholarship about the geographic extent of the Holocaust.