Theresienstadt: Cultural Life

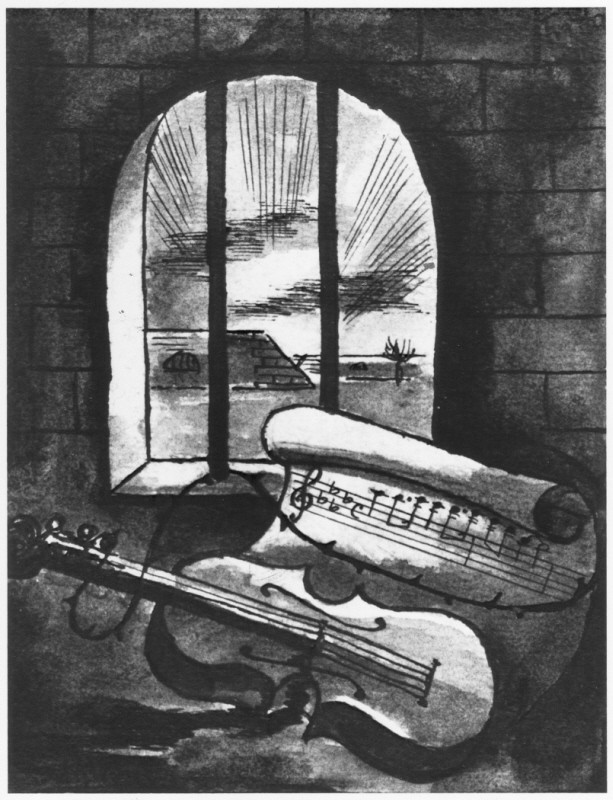

Despite the terrible living conditions and the constant threat of deportation, Theresienstadt had a highly developed cultural life. The distinctiveness of the camp-ghetto's cultural life lies first in the activities of thousands of professional and amateur artists, their concerts, theatrical performances, artworks, poetry readings, and above all the composition of musical works: an outpouring of culture under unimaginably difficult conditions, unparalleled in the Nazi camp system.

Theresienstadt was the only concentration camp in which religious life was practiced, more or less undisturbed, beginning with the celebration of the first night of Hanukkah in late December 1941. The ghetto library had more than 10,000 volumes in Hebrew. Both within and outside the framework of the "open university," more than 2,300 lectures (more than one for each day of the camp-ghetto's existence) were given on topics ranging from art to medicine, from economics to Jewish history.

Verdi's Requiem was performed in Theresienstadt. Composer Viktor Ullmann, a student of Arnold Schönberg, wrote 20 musical works, though he could not finish all of them before his deportation in 1944.

Other figures of European or worldwide significance who were prisoners at Theresienstadt were Ullmann's fellow composers Carlo S. Taube, Gideon Klein, Pavel Haas, and Zigmund Schul; the artists Bedrich Fritta (pseudonym for Fritz Taussig), Leo Haas, Felix Bloch, Max Placek, and Peter Kien, who was also a talented poet, as well as Friedl Dicker-Brandeis; the architect Norbert Troller; the theologian-philosopher Leo Baeck; and the author/composer of books and songs for children, Ilse Weber.

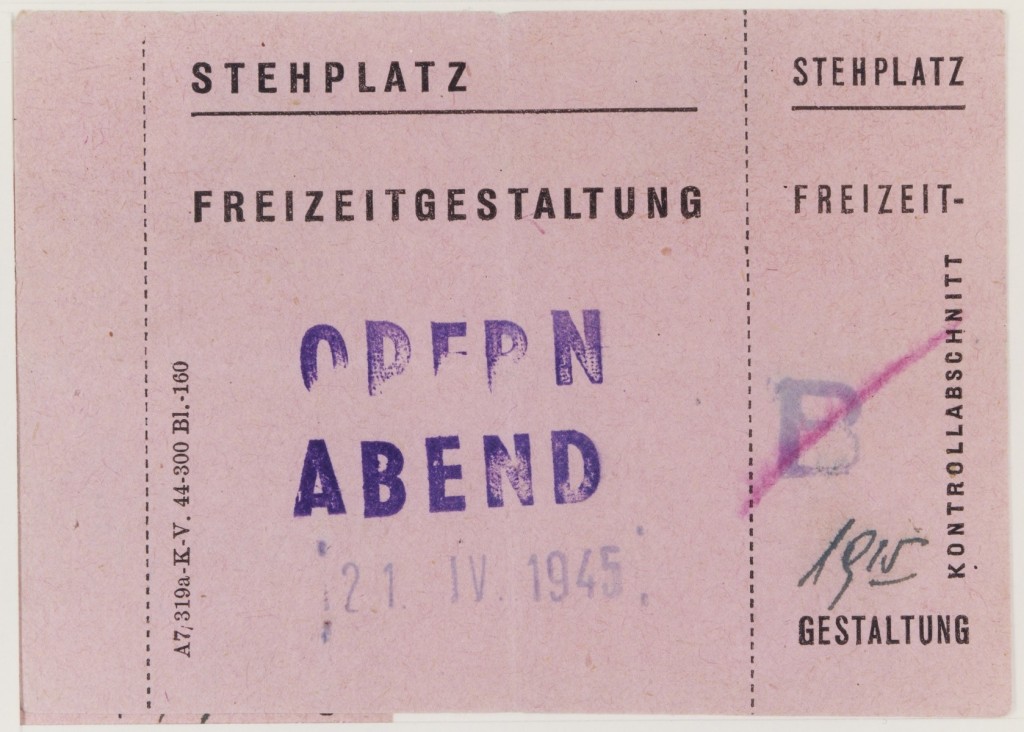

Victor Ullmann's opera, Der Kaiser von Atlantis; oder der Tod dankt ab (The Emperor of Atlantis; Or Death Resigns), written in collaboration with Peter Kien, is thought by many to be one of the most significant creations in the spiritual legacy of the Holocaust era. Remembered with equal emotion and reverence is the Theresienstadt prisoner Hans Krása's children's opera, Brundibár, which was performed 55 times during the existence of the camp-ghetto, and on one occasion during the 1944 visit of representatives from the International and Danish Red Cross.

Perhaps the most precious legacy of Theresienstadt is the collection of children's paintings—artwork which, beyond its own intrinsic value—is testimony to the courage of the children and their teachers, who continued to live, to teach, to paint, to learn, and to hope, despite the constant fear of violent death, a fear based on a realistic assessment of the situation in which they found themselves.

Critical Thinking Questions

How can producing art in any form be considered an act of resistance?

What can we learn from the artwork prisoners created under such extreme circumstances?

Research works of art produced in other camps and ghettos.