Arrests without Warrant or Judicial Review

Arrest without warrant or judicial review was one of a series of key decrees, legislative acts, and case law in the gradual process by which the Nazi leadership moved Germany from a democracy to a dictatorship.

Background: Preventive Police Action in Nazi Germany, as of February 28, 1933

The Nazis employed a comprehensive strategy to control all aspects of life under their regime. In tandem with a legislative agenda by which they unilaterally required or prohibited certain public and private behaviors, the Nazi leadership dramatically redefined the role of the police, giving them broad powers—independent of judicial review—to search, arrest, and incarcerate real or perceived state enemies and others they considered criminals.

The Supreme Court failed to challenge or protest the loss of judicial authority at this time. In general, it approved of the Nazi leadership's decisive action against left-wing radicals (e.g., communists) that seemed to be threatening the government's stability. Further, the Supreme Court had been the court of first instance for treason cases since the Imperial period but, by the 1930s, it was overburdened with such trials and had endured relentless criticism from all sides for the judgments it rendered. The court was ultimately relieved to have responsibility for political crimes removed from its jurisdiction.

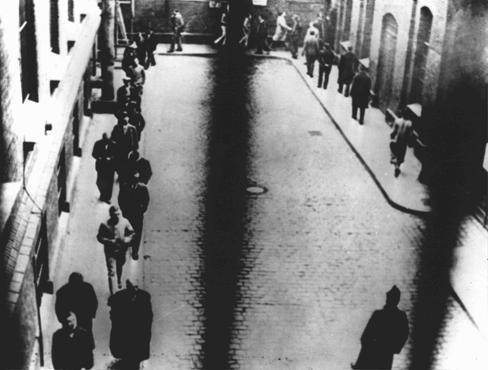

The security police (not to be confused with paramilitary units such as the SS or the SA, which also imposed public order) was composed of two primary arms: the Secret State Police (Gestapo), which investigated political opposition, and the Criminal Police (Kripo), which handled all other types of criminal activity. The Gestapo was empowered to use “protective custody” (Schutzhaft) to incarcerate indefinitely, without specific charge or trial, persons deemed to be potentially dangerous to the security of the Reich. Protective custody had been introduced in the German general law code before World War I to detain individuals for their own protection or to avert an immediate security threat if there were no other recourse. Now the Gestapo employed protective custody to arrest political opponents and, later, Jews, as well as Jehovah's Witnesses who, because of religious conviction, refused to swear an oath to the Nazi German state or to serve in the armed forces. Individuals detained under protective custody were incarcerated either in prisons or concentration camps; within two months of the Reichstag Fire Decree, the Gestapo had arrested and imprisoned more than 25,000 people in Prussia alone.

The Kripo used a similar strategy called “preventive arrest” (Vorbeugungshaft) to seize any individuals determined to be a threat to public order. As the guidelines show, the Kripo was given limitless power for surveillance and was authorized to seize persons on the mere suspicion of criminal activity. As with those held by the Gestapo under protective custody, those held by the Kripo under preventive arrest had no right to appeal or access to a lawyer, and their arrests were not liable to judicial review. They were generally interned directly in a concentration camp for a period determined by the police alone. By the end of 1939, more than 12,000 preventive arrest prisoners were interned in concentration camps in Germany.

Translation

Translated from Werner Best, Der Deutsche Polizei (Darmstadt: L.C. Wittich Verlag, 1940), pp. 31-33.

Guidelines for Preventive Police Action against Crime:

In the internal distribution of responsibilities of the police, prevention of “political crimes” is assigned to the Secret State Police [Gestapo]. In other cases the criminal police is responsible for the prevention of crime. The criminal police operates according to guidelines in the prevention of crime according to the following principles:

The tools used in the prevention of crime are systematic police surveillance and police preventive arrest.

Systematic police surveillance can be used against those professional criminals who live or have lived, entirely or in part, from the proceeds of their criminal acts and who have been convicted in court and sentenced at least three times to prison, or to jail terms of at least three months, for crimes from which they hoped to profit.

Further, habitual criminals are eligible if they commit crimes out of some criminal drive or tendency and have been sentenced three times to prison, or to jail terms of at least three months, for the same or similar criminal acts. The last criminal act must have been committed less than five years ago. The time the criminal spent in prison or on the run is not counted. New criminal acts that lead to additional convictions suspend this time limit.

All persons who are released from preventive police arrest must be placed under systematic police surveillance.

Finally, systematic police surveillance is to be ordered despite these regulations if it is necessary for the protection of the national community [Volksgemeinschaft ].

In the application of systematic police surveillance the police can attach conditions such as requiring the subject to stay in or avoid particular places, setting curfews, requiring the subject to report periodically, or forbidding the use of alcohol, or other activities; in fact, restrictions of any kind may be imposed on the subject as part of systematic police surveillance.

Systematic police surveillance lasts as long as is required to fulfill its purpose. At least once every year the police must reexamine whether the surveillance is still required.

Preventive police arrest can be used against the following:

Professional and habitual criminals who violate the conditions imposed on them during the systematic police surveillance of them or who commit additional criminal acts.

Professional criminals who live or have lived, entirely or in part, from the proceeds of their criminal acts and who have been convicted in court and sentenced at least three times to prison, or to jail terms of at least three months, for crimes from which they hoped to profit.

Habitual criminals if they have committed crimes out of some criminal drive or tendency and have been sentenced three times to prison, or to jail terms of at least three months, for the same or similar criminal acts.

Persons who have committed a serious criminal offense and are likely to commit additional crimes and thereby constitute a public danger if they were to be released, or who have indicated a desire or intention of committing a serious criminal act even if the prerequisite of a previous criminal act is not established.

Persons who are not professional or habitual criminals but whose antisocial behavior constitutes a public danger.

Persons who refuse to identify, or falsely identify themselves, if it is concluded that they are trying to hide previous criminal acts or attempting to commit new criminal acts under a new name.

Normally, police preventive arrest is to be used against these persons if it is concluded that the more mild measure of systematic police surveillance will unlikely be successful.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What pressures and motivations may have affected members of the legal profession as the Nazi government consolidated its power in the 1930s?

- What is the appropriate relationship between a government and the judiciary?

- What is the appropriate relationship between ideology and the judiciary?