The Oneg Shabbat Archive

The Oneg Shabbat underground archive was the secret archive of the Warsaw ghetto. The term Oneg Shabbat, which refers to the traditional Sabbath gathering of members of the community, was applied to the underground archive because its organizers held their regular, clandestine meetings on the Sabbath.

Key Facts

-

1

Begun as an individual chronicle by Emanuel Ringelblum in October 1939, the archive grew into an organized underground operation with several dozen contributors after the sealing of the ghetto in November 1940.

-

2

The workers of the archive faced constant danger. They collected an enormous range of material, including items from the underground press.

-

3

The holdings of the archives were buried in three parts. After the war, two of the three caches of documents were recovered.

The Archivists

Initially, the archivists of Oneg Shabbat collected reports and testimonies by Jews who had come to the ghetto to seek help from the self-aid organizations. Emanuel Ringelblum organized the Oneg Shabbat archive around the networks of the Aleynhilf (self-help organization)—using the refugee points, soup kitchens, house committees, and underground schools to provide the information, documents, and testimonies for the archive.

Through new contacts in the Aleynhilf, Ringelblum recruited much of the nucleus of the Oneg Shabbat archive. He brought in key people such as Hersh Wasser, Eliyahu Gutkowski, David Cholodenko from Lodz, and Rabbi Shimon Huberband from Piotrkow. Ringelblum also recruited heavily from his trusted friends in the prewar YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC): Yitzhak Gitterman, Shmuel Winter, Shie Rabinowitz, Menakhem Linder, Abraham Lewin, and Rachel Auerbach, among others.

The workers of the archive Oneg Shabbat faced constant danger. Interviewing refugees in the filthy and overcrowded refugee centers exposed them to the risk of contracting typhus. There was also the ever-present threat of Gestapo agents. One of Ringelblum's greatest achievements was that the Germans never stumbled on the secret.

The two secretaries of the archive, Hersh Wasser and Eliyahu Gutkowski, played critical roles. Along with Ringelblum, they kept track of the archive's daily activities, checked ongoing projects, and made sure that writers completed their assignments. Wasser, a member of the Po'alei Zion Left and Gutkowski, of the Po'alei Zion Right were also active in the underground press and fed it with information from Oneg Shabbat.

The archive established links with the two major Zionist youth organizations in the ghetto, Dror-Frayhayt and Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa'ir. Gutkowski was the key contact with Dror, while Ringelblum enjoyed a close friendship with the leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa'ir, including Mordecai Anilewicz, who would later become the commander of the Jewish Fighting Organization. Two other leaders of Ha-Shomer, Shmuel Breslaw and Joseph Kaplan, also served on the executive committee of the Oneg Shabbat. In this way the archive was in a position to follow the establishment of a resistance movement in the ghetto.

Creating a Historical Record

Ringelblum and his associates collected information during the day, writing notes at night. Ringelblum knew that the Nazi persecution of the Jews was unprecedented, and he was determined to create a historical record for future historians. He and his colleagues collected data and wrote about daily life in the ghetto, specific Jewish communities, Jewish participation in the September 1939 campaign, forced labor, Judenrat (Jewish council) policy, the work of the social welfare institutions in the ghetto, the fate of Jewish children, and religious life in the ghetto. They wrote about resistance in its several forms, including cultural work, underground schools, the underground press, and smuggling, as well as armed resistance.

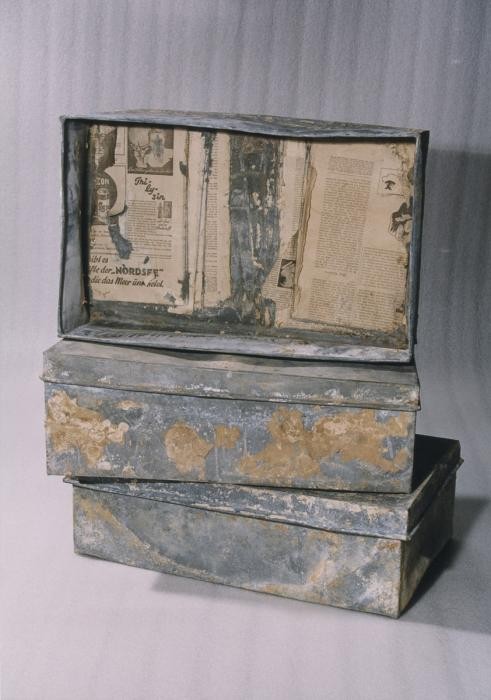

The Oneg Shabbat archive collected an enormous range of material, including items from the underground press, documents, drawings, candy wrappers, tram tickets, ration cards and theater posters. It saved literature: poems, plays, songs, and stories. It filed away invitations to concerts and lectures, copies of the convoluted doorbell codes for apartments that often contained dozens of tenants, and restaurant menus from the “ghetto cabarets” that advertised roast goose and fine wines. Carefully gathered were hundreds of postcards from Jews in the provinces about to be deported to an “unknown destination.” The first cache of the archive also contained many photographs, 76 of which more or less survived.

After July 22, 1942, the archive collected the German posters that announced the great deportation. Desperate appeals from those waiting to board deportation trains (to Treblinka) were crammed into the archive, as were the later posters calling for armed resistance in 1943.

The commitment to comprehensive documentation went hand in hand with another important commitment: postwar justice. The quest to gather evidence explains why the archive collected enormous amounts of material on events in as many localities as possible. This material, often repeated, helped to document town by town and village by village what the Germans did, when they did it, who gave the orders, and who helped them. The chroniclers of the Oneg Shabbat felt a responsibility to document; if they did not do this, then who would?

The work of the Oneg Shabbat archive did not stop even when hundreds of thousands of Jews—including several members of the archive itself—were deported from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka in the summer of 1942. During those days, the documentation already gathered was buried underground. In January and April 1943, more sections of the archive were buried.

Burying the Archive

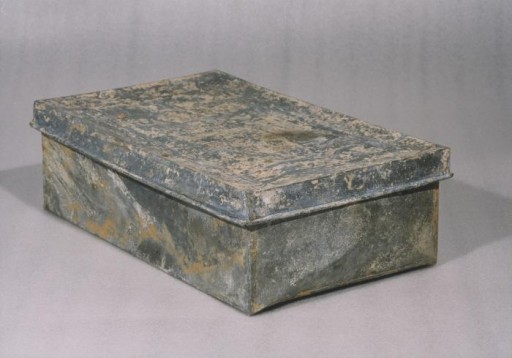

The holdings of the archives were buried in three parts. The first set of documents was placed in 10 tin boxes by the teacher Israel Lichtensztajn and two of his former students, Dawid Graber and Nachum Grzywacz. On August 3, 1942, the boxes were buried in a bunker beneath the former public school building where Lichtensztajn had taught at 68 Nowolipki Street. In February 1943 Ringelblum and Lichtensztajn placed the second part of the archive in two large milk cans and buried them beneath the same building. On April 18, 1943, just one day before the start of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, the third and final part of the archives was placed in a cylindrical metal box and buried beneath a building located at 34 Swietojerska Street.

In March 1943, Ringelblum and his family escaped the ghetto and went into hiding in the non-Jewish area of Warsaw. During Passover of that year, he returned to the ghetto, which was in the midst of the ghetto uprising. He was deported to the Trawniki labor camp, but escaped with the help of a Polish man and Jewish woman. He went back into hiding with his family, however, in March 1944 their hideout was discovered. Soon after, Ringelblum, his family, and the other Jews he had been hiding with were taken to the ruins of the ghetto and murdered.

Recovering the Archive

After the war, two of the three caches of documents were recovered. Two surviving members of the Oneg Shabbat staff, Rachela Auerbach and Hersz Wasser, led members of the Jewish Historical Commission of Poland to the first burial site. The 10 metal boxes were recovered on September 18, 1946. The second portion of the archives was uncovered on December 1, 1950. The final cache was never found.

The many documents gathered by the archival staff of the Oneg Shabbat constitute a vital testimony both to the depth of suffering and the dignity of the Jews of Poland as a whole, and the Jews of Warsaw in particular, who sought to continue life in any way possible under Nazi occupation. Alongside the hunger, crowding, and constant distress, Jews in the Warsaw ghetto managed to live a rich spiritual life. Without the Oneg Shabbat archive, we would know little about this life. At the same time, the archive itself documents the indomitable spirit of its team of collectors and its leader, Emanuel Ringelblum, who devoted themselves to ensuring that future generations would have an accurate picture of Jewish life during the Holocaust.

Critical Thinking Questions

What may have motivated the workers of the Oneg Shabbat archive to continue to collect materials, despite the constant risk of danger?

What types of materials were preserved in the Oneg Shabbat archive? What can these materials teach us about Jewish life in the ghetto?

How can documenting be a form of resistance?