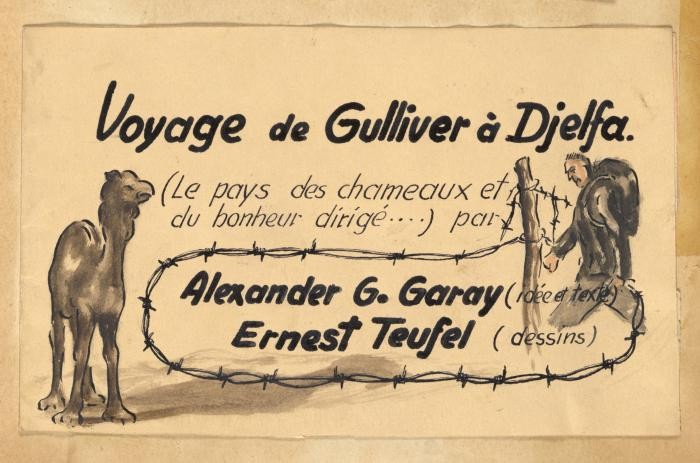

Labor and Internment Camps in North Africa

In Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and French West Africa, French collaborationist Vichy authorities established a network of different types of camps: penal camps, labor camps, and internment camps. These camps included Jewish and non-Jewish European refugees, those already residing in French colonial North Africa before 1940, those deported for forced labor in the Sahara, Allied prisoners of war, and civilians.

On June 22, 1940, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud of France surrendered to the German army, leading to the signing of the French-German Armistice. The treaty established a zone of German occupation in northern and western France, with southern France falling under the rule of a new collaborationist government based in Vichy, under the direction of Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain. Pétain and the Vichy regime retained administrative control over France’s overseas territories in North Africa, including colonial Algeria and the protectorates of Morocco and Tunisia. With these developments, Vichy North Africa became a unique site of World War II where colonialism and fascism co-existed and overlapped.

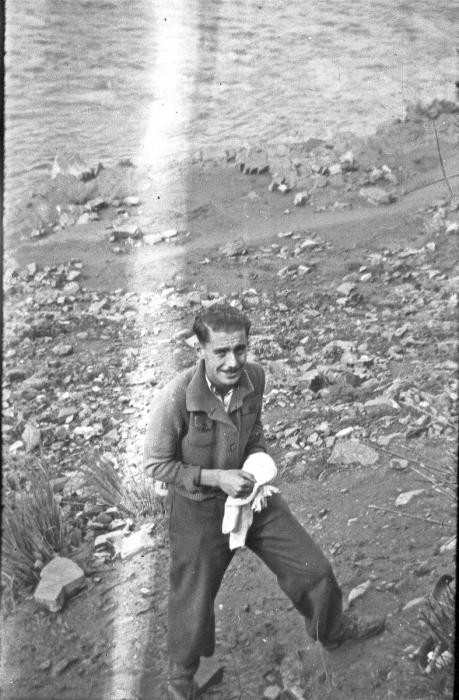

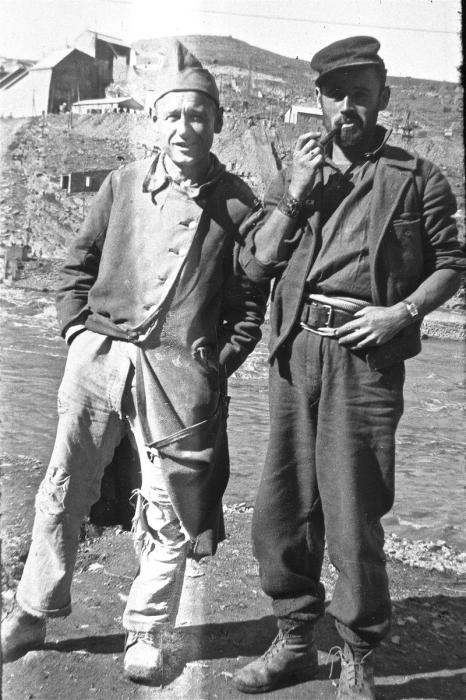

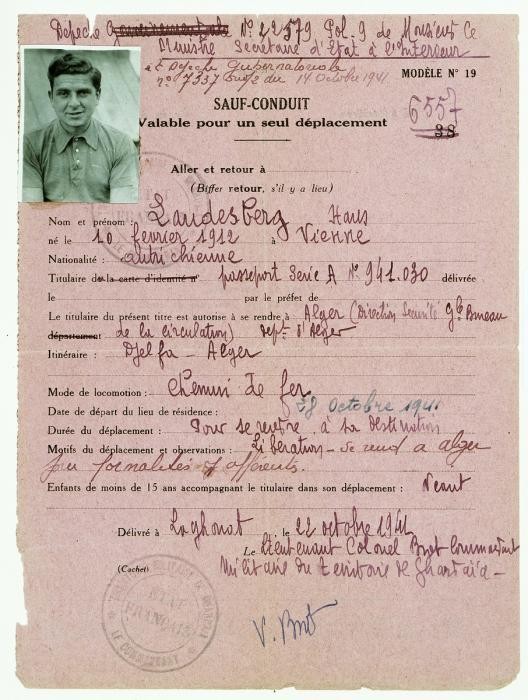

The majority of residents of Vichy North Africa were Muslims and Jews native to the region. European settler colonialists also lived across North Africa. Additionally, Vichy North Africa was a temporary home to thousands of refugees, including Jews, from virtually every country in Europe. Some of these women and men had survived the Spanish Civil War as civilians or volunteers for the Spanish Republican Army, while others reached North Africa from other parts of the continent, after fleeing the threat of war, violence, or race laws. Many refugees made the journey to North Africa before the German occupation of northern and western France, and hence before the Vichy regime was created. After the Vichy regime was established, all of these displaced populations were prone to arrest as “undesirables” or foreigners, and many were subsequently sent to labor camps for internment.

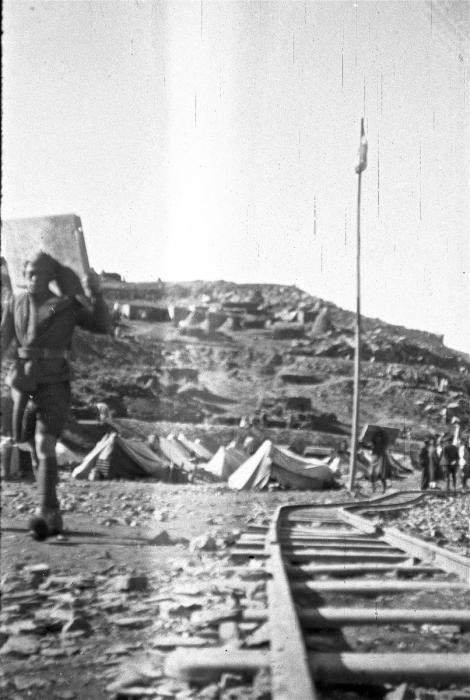

In 1940, Vichy authorities ordered an extended networks of labor camps to be created or repurposed in North Africa (including Algeria and Morocco) and French West Africa (including Senegal, Mali, Guinea) to hold these foreign refugees and dissidents. In Morocco and Algeria, many of these camps were designed to further a railroad project known as the Mediterranean-Niger (Mer-Niger) line. French colonial administrators conceptualized and initiated this project in the nineteenth century, hoping to connect the Senegalese city of Dakar to the coastal cities of Algeria. Disagreements within the French leadership stymied this venture, however, and the Mer-Niger railroad remained an unrealized dream of the nineteenth century.

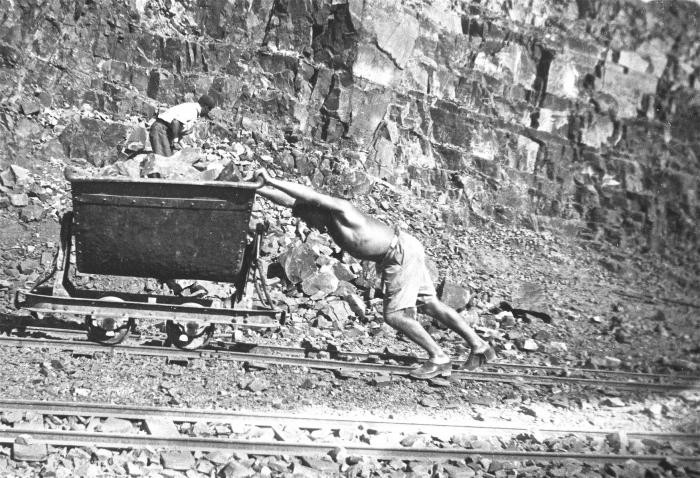

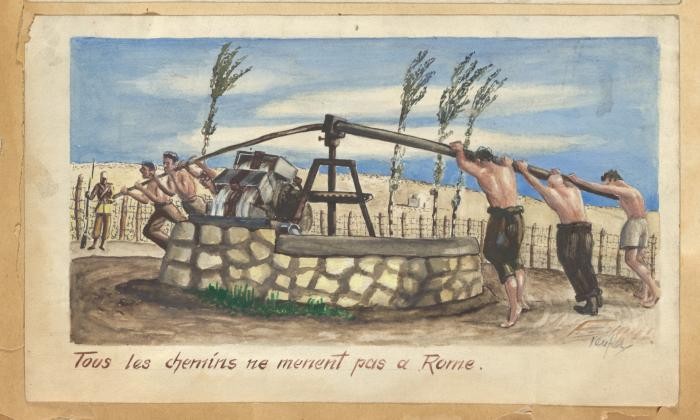

During World War II, the railway took on new meanings. Nazi officials supported the project, seeing it a useful way of moving Senegalese soldiers through the Saharan desert, and as a vehicle to exploit the large quantity and variety of mineral and natural resources (including coal) that could be found in the region. Recruiting workers to the harsh desert environment proved an obstacle, however, until the Vichy Minister of the Interior authorized the deployment of slave labor to the Sahara. Most of those who were subjected to forced labor in these locations were “undesirables” and foreigners.

In early 1941, the Vichy authorities transferred hundreds of refugees, including women and children, to the Saharan labor camps as well as other kinds of detention centers. Foreign Jews constituted a significant percentage of the imprisoned, even if they were not specifically arrested for being Jews. In Algeria, for example, it was estimated that 2,000-3,000 Jews were interned in camps with political prisoners of different backgrounds, resulting in a total prisoner population of 15,000-20,000.

The political prisoners and internees were largely organized into groups of foreign workers: the Groupements de Travailleurs Étrangers (Groups of Foreign Workers; GTEs); Groupements de Travailleurs Étrangers Autonomes (Autonomous Groups of Foreign Workers; GTEAs); and Groupements de Travailleurs Démobilisés (Groups of demobilized foreign workers; GTDs). Other forced laborers and internees included Spanish Republicans, political prisoners, and former Jewish volunteers to the French Foreign Legion (Légion étrangère, LE). It appears that very few (if any) Moroccan Jewish nationals were sent to the Vichy camps in Morocco. In Algeria the numbers of local Jews deported was higher, and included Algerian Jewish veterans.

The Ministry of Industrial Production and Labor was tasked with the management of the Vichy camps, and with the oversight of the internees. In cases of unrest and/or the refusal to follow orders, and when the regime required more forced labor, internees were moved from camp to camp. All told, these camps constituted a vast network, mostly located along the railroads and close to mines.

The day-to-day administration of Vichy camps in Morocco and Algeria was carried out by Senegalese infantry (tirailleurs), Muslims conscripted or paid to join the auxiliary service, by local Moroccan military auxiliary representatives (goumiers), and by members of the French cavalry recruited from indigenous tribal groups (spahis). The prisoner population these forces controlled tended to be made up of distinct classes of prisoners. For instance, the camps of Djelfa, Djenien Bou Rezg, and Hadjerat M’guil housed mainly political dissidents, while Bou Arfa and Colomb-Béchar were reserved for GTEs.

Other types of prisoners were confined to Vichy labor camps in French West Africa. Here, French authorities established six camps, mostly to intern Allied prisoners of war and the crews of Dutch Greek, Danish, and British military or commercial ships. These camps were located in Mali (Tombouctou and Koulikoro); Senegal (Sebikotane); and Guinea (old French Guinea) (Conakry, Kinda and Kankan).

Memoirs, diaries, and poetry written by the interned testify to the hardship of everyday life in the Vichy labor camps. In the forced-labor camps of southern Morocco and Algeria, detainees faced harsh punishment, including beatings and incarceration in “the tomb,” a hole in which prisoners were forced to sleep for 25 to 30 days without movement of any kind. Prisoners who attempted to move within this confined space were ruthlessly abused. Another form of punishment was confinement to “the lion cage,” an 1.80-meter (1.9-yard) cube surrounded by barbed iron threads. Food was limited to 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of bread and water per day, and many internees died from scorpion stings, snake bites, typhoid, and malaria. Heat and cold were suffered with scant clothing, blankets, or shoes.

In Tunisia, circumstances diverged from those in Morocco and Algeria. To begin with, the labor and detention camps in Tunisia were overseen by French, German, and Italian overseers, depending on the timing of war. Some forty German labor and detention camps were constructed in Tunisia after the Allied landings, when Germany began a six month occupation of Tunisia (November 1942-May 1943). It is estimated that roughly 5,000 Tunisian Jewish men were conscripted for forced labor within these spaces of confinement. At the same time, Jewish men were inducted into forced labor near the front lines and within cities like Tunis.

Libya was a key battleground of World War II, and territory here passed back and forth between Italian and British hands. German forces, too, represented the Axis in Libya. Benito Mussolini ordered the Jews of Cyrenaica moved out of the war zone—ostensibly to prevent them from aiding the British—in February of 1942. Most of the 2,600 Jews deported as a result of his orders were sent to the camp of Giado, a former military post located 150 miles south of Tripoli. Other Libyan Jews were deported to the camps of Buqbuq and Sidi Azaz. Inmates were subjected to forced labor in all three camps, with conditions in Giado proving particularly harsh. In addition, the Italians deported some Libyan Jews to internment camps in Tunisia.

Jewish and non-Jewish organizations and relief agencies such as the America Joint Distribution Committee and the American Friends Service Committee sought to support the women, men, and children interned in the North African camps. Individuals such as Hélène Cazès-Benathar, who represented the JDC in Casablanca, directed aid to internees they viewed as non-political.

Despite these philanthropic efforts, the Vichy camps were not immediately closed following Operation Torch (the Anglo-American invasion of French Moroccan and Algeria) that concluded on November 16, 1942. This was a profound and lasting insult to the internees and their families and advocates. It took many months—in cases, years—before the Vichy regime’s fantastical railroad project was abandoned , its camps opened, and its prisoners released.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Learn about the diverse Jewish communities of North Africa before World War II.

- What was the relationship between German expansion and the fate of Jews in North Africa?

- Explore recent scholarship about the geographic extent of the Holocaust.