Polish Jewish Refugees in Lithuania: Unexpected Rescue, 1940–41

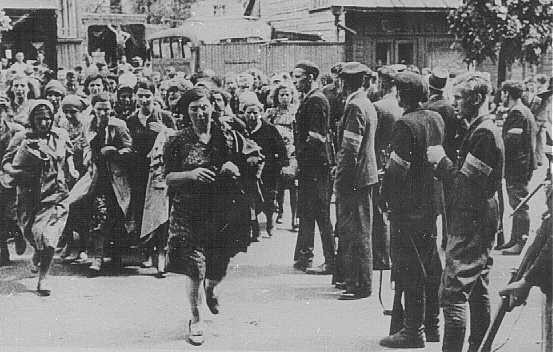

The outbreak of war in Poland in September 1939 trapped nearly three and a half million Jews in German- and Soviet-occupied territories.

In late 1940 and early 1941, just months before the Germans began to implement the mass killings of Jews, one group of about 2,100 Polish Jews found a safe haven. Few of these refugees could have reached safety without the tireless efforts of many individuals. Several Jewish organizations and Jewish communities along the way provided funds and other help.

The most critical assistance came from unexpected sources: representatives of the Dutch government-in-exile and of Nazi Germany's Axis ally, Japan. Their humanitarian activity in 1940 was the pivotal act of rescue for hundreds of Polish Jewish refugees temporarily residing in Lithuania.

After the Soviet takeover of Lithuania, Polish Jewish refugees who had sought a safe haven in neutral Lithuania once more felt trapped. Germany's invasion of western Europe a few weeks earlier and the fall of the Low Countries (the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) and France shattered any illusions of a quick end to war in the west. Options for escape were few, and all required diplomatic permits—visas—to cross international borders. When the Soviets ordered all diplomatic consulates closed by August 25, 1940, time began to run out. Without visas, the refugees would be stuck in Communist-controlled Lithuania.

The refugees' preferred destinations were the United States and British-controlled Palestine, but rigorous laws and policies restricted entrance to both places. The US Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act) was still in effect in 1940. It set strict numerical quotas for immigrants to the United States. Consuls abroad could issue only 6,524 visas to Polish nationals, and in 1940 there was a two-year waiting list for these "quota" visas. Emigration to Palestine was also very difficult. A British White Paper issued on May 17, 1939, limited the number of Jews allowed to enter the British-controlled Mandate of Palestine from all countries to 15,000 annually.

The only hope was to bypass standard immigration procedures with the help of organizations abroad. Even with the sponsorship of an American organization, however, time ran out when consulates in Lithuania closed. The American consul was able to issue only 55 visas. The British envoy released 700 Palestine certificates to Zionist youth, rabbis, and other groups. Hundreds of others still needed visas to get out of Lithuania.

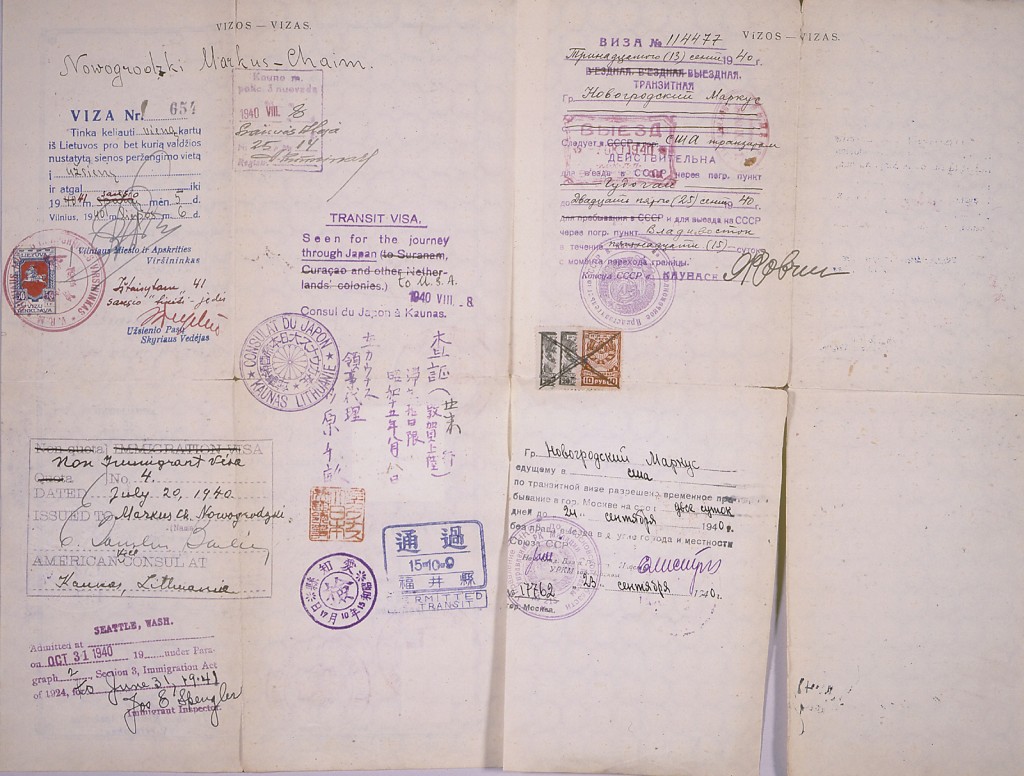

A fortunate few escaped via an eastward, Asian route, using an odd combination of permits: a bogus visa for entry to the Dutch Caribbean island of Curacao, a place that few of the refugees had even heard of, and a visa for transit through Japan. The breakthrough in the visa dilemma came unexpectedly at the Dutch consulate in Kovno. L.P.J. de Decker, the Dutch minister to all three Baltic states, authorized his acting consul in Lithuania, Jan Zwartendijk, to issue permits declaring that "an entrance visa is not required for the admission of aliens to Surinam, Curacao, and other Dutch possessions in America." Consciously omitted was the key fact that admission was the prerogative of the colonial governors, who rarely allowed it.

Escaping war-torn Europe to reach Curacao in the Caribbean meant crossing the Pacific Ocean, a route made possible by Japan's acting consul to Lithuania, Chiune Sugihara. In the absence of clear instructions from Tokyo, he granted 10-day Japanese transit visas to hundreds of refugees who held Curacao destination visas. Before closing his consulate, Sugihara even gave visas to refugees who lacked all travel papers.

In January 1941 hundreds of refugees with only Curacao "visas" began arriving in Japan and were unable to proceed to other countries. The Japanese Foreign Ministry cabled Sugihara to ask him how many transit visas he had issued in Lithuania. On February 28, 1941, Sugihara sent a list of 2,140 persons. Some 300 others, mostly children, were covered by these visas, issued from July 11 to August 31, 1940.

Not everyone who held visas was able to leave Lithuania, however, before Soviet authorities ceased issuing exit visas.