Heinrich Hoffmann

Heinrich Hoffmann (1885–1957) was a Nazi Party member, a professional photographer, and a close associate of Adolf Hitler. Hoffmann’s photographs helped create and shape the public image of Hitler.

Key Facts

-

1

Beginning in the early 1920s, Hoffmann took numerous photographs of Hitler in a variety of circumstances, including at home, at Nazi rallies, and during major world events.

-

2

Hoffmann became wealthy as a result of his images of Hitler and his relationships with Hitler and other Nazi leaders.

-

3

After World War II, Hoffmann was categorized as a Major Offender in the denazification process.

Few people played a greater role in the creation of the “Hitler myth” than German photographer Heinrich Hoffmann. Beginning in the early 1920s, he worked with Adolf Hitler to create a strong public image of the Nazi leader that resonated with millions of Germans. Hoffmann’s numerous photographs of Hitler helped to brand and advertise Hitler and the Nazi Party. Hoffmann was an early member of the Nazi Party who worked on its behalf until Nazi Germany’s defeat in 1945. After World War II, however, he attempted to present himself as merely an “apolitical” photographer.

Heinrich Hoffmann’s Early Career

Heinrich Hoffmann was born in 1885 in the Bavarian town of Fürth. His father was a photographer who operated a studio with his brother, first in Regensburg and later in Munich. Building on this family profession, Hoffmann became an apprentice. He traveled throughout Germany and to London to study with respected photographers. Hoffmann then set up his own photography studio in Munich. He later expanded his business to include press photography and postcards. Hoffmann quickly earned a local reputation for both his portraits and his images of contemporary events.

On August 2, 1914, Hoffman brought his camera to Munich’s Odeonsplatz. He photographed the crowd celebrating Germany’s entrance into World War I (1914–1918). A few years later, Hitler told him that he had attended the same event. Hoffmann then searched through enlarged copies of his prints. He discovered that he had captured a young and jubilant Hitler among the thousands of Germans there that day.

Shortly after the event in Munich, Hoffmann went to the western front to take press photographs. According to Hoffmann, there were only seven people serving as war photographers in Germany in 1914, and he was the only one from Bavaria. In summer 1917, he was conscripted into the German armed forces.

Hoffmann returned to Munich in 1918. That November, he witnessed the German Revolution, when the Bavarian monarchy was toppled. Hoffmann quickly seized the opportunity to document the event. He photographed the leading participants, lugging around a large format glass plate camera. Hoffmann’s politics at this stage remain a bit murky. However, it seems clear that he took advantage of the political changes to sell his photographs and postcards.

By the fall of 1919, Hoffmann’s political outlook took a decidedly far-right turn.

Hoffmann’s Role in Early Nazi Politics

Hoffmann joined the Nazi Party on April 6, 1920. At this time, the party was still rather small and centered in Munich. Hoffmann received a membership card inscribed with the number 427. In May 1920, the Nazi Party had only 675 members.

Hoffmann first began photographing Nazi Party events in early 1923. Later that year, he started to take pictures of Hitler and other Nazi leaders. Hoffmann photographed Hitler and the other defendants on trial for high treason for their role in the Beer Hall Putsch. He also documented Hitler’s release from Landsberg prison in 1924. That same year, Hoffmann published his first photographic pamphlet in support of the Nazi Party. It was titled Deutschlands Erwachen in Wort und Bild (Germany’s Awakening in Word and Picture).

Relationship with Adolf Hitler

Hoffmann’s connections to the Nazi leadership proved to be crucial and ultimately financially lucrative to both the photographer and the Nazi Party. His fortunes increased and declined along with those of Hitler and the Nazis.

Hoffmann soon became part of Hitler’s inner circle. Both men had aspired to be painters and had served in the German army during World War I. They often discussed art. Perhaps more significantly, they came to understand the importance of images to the success of Nazi politics.

Hitler was a frequent visitor to the Hoffmann home and attended family gatherings there. In October 1929, Hitler met 17-year-old Eva Braun at Hoffmann’s photo shop. An apprentice, Braun sold camera film and developed photographic negatives. Ultimately, she became Hitler’s mistress and, in the final days of the Nazi regime, his bride. Hoffmann’s daughter, Henriette, also became part of the Nazi inner circle. She married Baldur von Schirach, the leader of the Hitler Youth and later Nazi Party chief in Vienna.

Hoffmann’s relationship with Hitler continued to grow throughout the 1930s.

Role During the Growth of the Nazi Party

As the Nazi Party grew in strength and popularity, there was a demand for photographs of its leadership, rallies, and election materials. Mainstream newspapers wanted images to satisfy their readers’ interests and to enhance written articles. Hoffmann’s photo studio expanded to accommodate the new workload.

In 1926, the Nazi Party established its own illustrated newspaper, Illustrierter Beobachter (Illustrated Observer). The newspaper served as a competitor to more mainstream publications, like Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung (Berlin Illustrated Newspaper) and Münchner Illustrierte Presse (Munich Illustrated Press). It was also a competitor to the Communist Party’s Die Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (The Worker’s Illustrated Newspaper). Hitler hoped that the Nazi press would help to break what he claimed was “Jewish control” of the media. Hoffmann played a leading role in the Nazi publication. He also convinced Hitler to include photos in the Nazi Party’s main newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter (People's Observer).

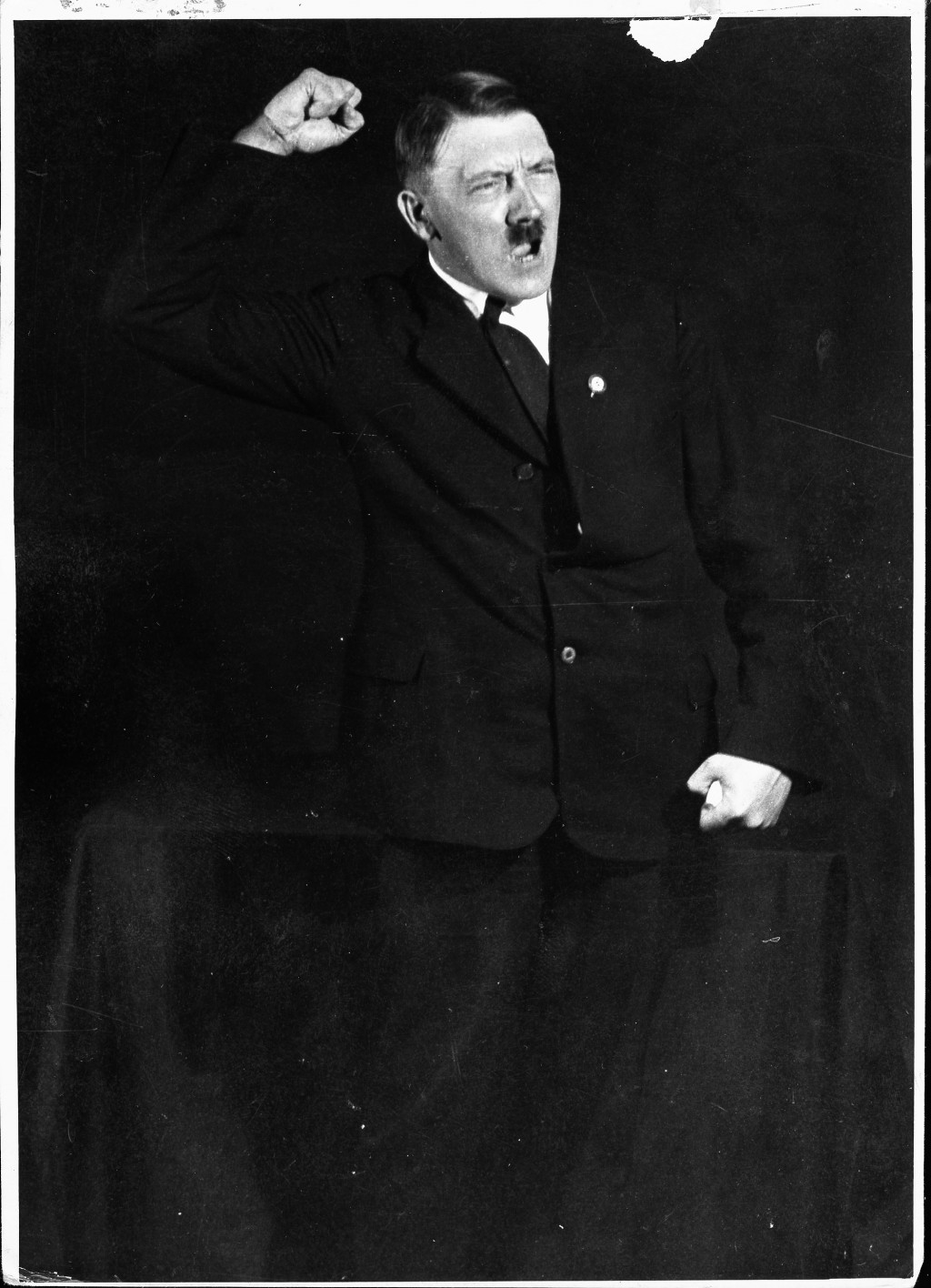

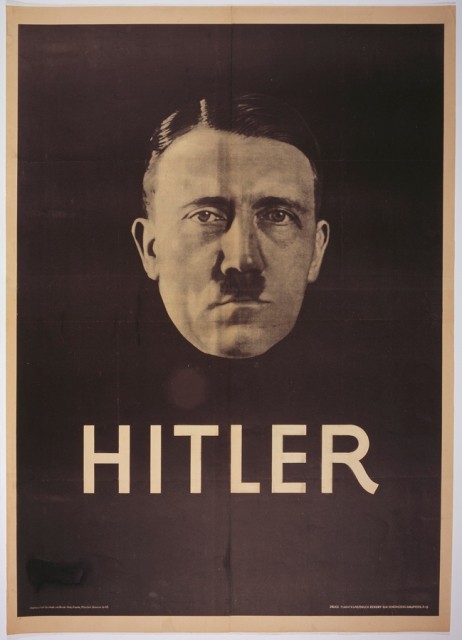

By 1932, the Nazi propaganda machine had constructed an effective image of Hitler, in part due to Hoffmann’s work. Hoffmann traveled with Hitler during his campaigns for German president and during the parliamentary elections. Whether Hitler was on board Lufthansa planes or in huge halls like Berlin’s Sportpalast (Sports Palace), Hoffmann was there with his trusty 35mm Leica camera. As Nazi popularity soared, Hoffmann’s business increased. Demand grew from both the Nazi Party and the mainstream press. Hoffmann’s monopoly on images of the Nazi leadership secured him profits and readers.

Hoffmann and Nazi Propaganda

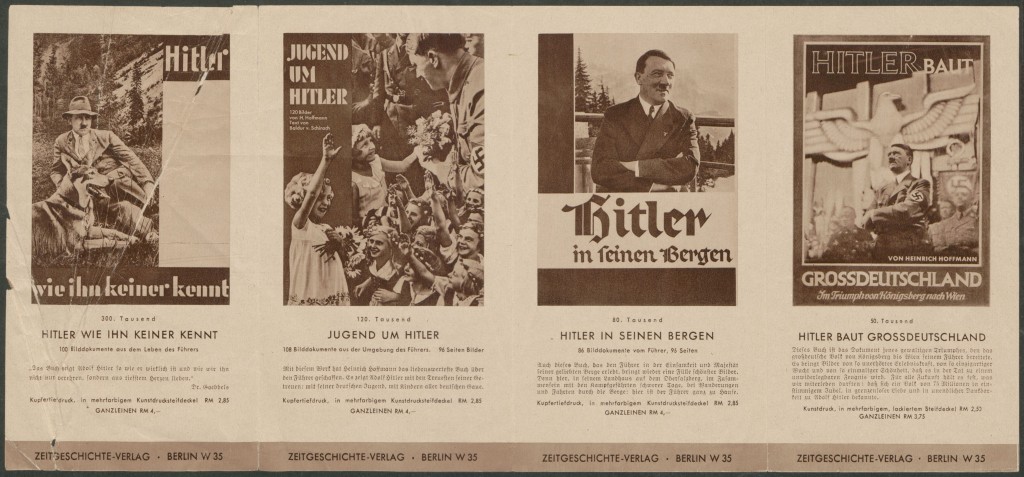

In 1932, Hoffmann published a series of photo books using images he had taken over the years. He sought to convey a positive image of Hitler and the Nazi Party. Using “candid” shots, Hoffmann presented Hitler as the “unknown German” who came from humble origins to serve his people heroically in World War I. He also depicted the Nazi leader as a savior who would rescue Germany from its troubles. Hitler was often shown with smiling children, with adoring audiences, or in deep thought. In addition, Hoffmann conveyed the diverse audiences drawn to Hitler. These included workers, professionals, and farmers, as well as Germans of all ages, genders, and regions.

Such photographic propaganda cemented the idea that Hitler spoke for all Germans, regardless of class, religion, and state. Hoffmann helped promote the notion that the Nazi Party was creating a Volksgemeinschaft (“national community”) in which all ethnic Germans would be united in a common purpose. This “national community” would supposedly be free of class, religious, and regional conflicts. Such appealing imagery aimed to negatively brand the Weimar Republic, Germany’s government before the Nazi rise to power. The Weimar Republic was portrayed as a state where social disharmony and political parties’ special interests reigned.

Hoffmann and other Nazi propagandists also attempted to whitewash the SA and the SS. SA and SS members frequently beat up political opponents and Jews. However, Hoffmann portrayed them as a “brown army,” disciplined and orderly, like the German troops of the past. He depicted the SA and SS—not their political foes—as the victims. Hoffmann often showed them with bandaged heads or as martyrs who died for the cause of a “free” Germany.

Hoffmann After the Nazi Rise to Power

Hoffmann’s fortunes rapidly increased after Hitler came to power in January 1933. From a rather small operation, Hoffmann’s business expanded both geographically and financially. He eventually established offices in Berlin, Düsseldorf, and Vienna. After the German occupations of eastern and western Europe, he opened offices in Prague, Posen (Poznań), Paris, the Hague, Strasbourg, and Riga. By 1943, Hoffmann had more than 300 employees, and his enterprises were bringing in millions of Reichsmarks.

Hoffmann’s photos appeared in newspapers in Germany and abroad, conveying Nazi propaganda throughout the world. His photographic empire broadened to include inserts for popular cigarette books and several dozen photo books of Hitler, other Nazi leaders, and events. He continued to have almost unfettered access to Hitler, at least until 1943. This access gained him titles and positions. For example, Hoffmann was named one of the curators of the Great German Art Exhibition. The role allowed him to help select suitable works of art for public display at the annual show. He was also able to make reproductions of the artwork, which he sold as postcards and in other formats. In addition, Hoffmann was given the title of professor and awarded a seat in the Nazi Reichstag. Lastly, he was named the Reich Photoreporter for the Nazi Party. This position guaranteed him exclusive rights and profits.

At every stage in the development of Nazi Germany, Hoffmann used his camera to further the regime’s propaganda. For example, he presented Germany as a peace-loving neighbor to France for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. Hoffmann also depicted Hitler as the architect of a new Germany, forging the “national community” and creating jobs. Later, he portrayed Germany as a defender against communism and as the victim of Polish and Anglo-French aggression. All the while, Hoffmann recorded the events of his time. For instance, he photographed the signing of the German-Soviet Pact in August 1939. This notorious pact opened the door to the invasion of Poland and the political dismemberment of eastern Europe.

Postwar Justice and Hoffmann

American authorities arrested Hoffmann when World War II ended in Europe in May 1945. Hoffmann was interrogated about various issues, including the Nazi looting of artwork in occupied Europe. US authorities seized his photographic collection and four original watercolors painted by Adolf Hitler. In October, Hoffmann was transferred to Nuremberg. He was assigned to organize his photographs and those taken by others as evidence in the International Military Tribunal’s cases against major Nazi war criminals. This angered some of the defendants, who had once been some of Hoffmann’s best subjects and clients.

Hoffmann was released from duty shortly after the tribunal sentenced the defendants. However, Bavarian authorities then arrested him. Hoffmann was brought before a denazification court. In January 1947, he was convicted as a Major Offender, the highest category. The court sentenced him to ten years of hard labor and confiscated his assets, with the exception of some funds to support his family. Hoffmann also lost his right to vote and was banned from his profession for ten years. He appealed, and his sentence was reduced. Hoffmann was released in 1950.