Volksgemeinschaft (People’s or National Community)

Beginning in the 1920s, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party emphasized their desire to create a Volksgemeinschaft (People’s or National Community) based on the foundations of race, ethnicity, and social behavior. Once in power, the Nazis aimed to shape a Volksgemeinschaft according to their ideological goals.

Key Facts

-

1

The Nazi Party sought to unify the German people under its leadership. It excluded groups and individuals that the Nazis considered racially, biologically, politically, or socially “undesirable.”

-

2

The Nazi state offered incentives to those Germans who joined the “national community.” It persecuted those who were deemed outside of it.

-

3

Ultimately, Nazi efforts to create a “national community” aided in the persecution and systematic mass murder of individuals and groups who were excluded from membership.

In 1933, the Nazis had no blueprint for the murder of Europe’s Jews. What came to be known as the Holocaust required a combination of many factors and decisions over time. Among these factors were extreme ideology, hatred of Jews, and racism. This article explores the concept of the “national community” in Nazi ideology.

Introduction

The term Volksgemeinschaft means “National Community” or “People’s Community.” It dates back to the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century in Germany. This concept was not strictly defined. It was applied in a variety of ways. Among the various groups who adopted the term were monarchists, conservatives, liberals, socialists, and avowed racist organizations. Each political party and its supporters gave the term a different meaning and goal.

Beginning in the 1920s, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party emphasized their desire to create a Volksgemeinschaft based on the foundations of race, ethnicity, and social behavior. Once in power, the Nazis aimed to build a Volksgemeinschaft according to their ideological goals. They sought to unify the German people under their leadership. They excluded groups and individuals that they considered racially, biologically, politically, or socially “undesirable.” Those excluded from membership included Jews, Black people, and Roma and Sinti (pejoratively labeled “Gypsies”). Also excluded were ethnic Germans whose political or social behavior did not align with the beliefs of the Nazi regime. The Nazi state offered incentives to Germans who joined the “national community.” It persecuted those who were deemed outside it.

Nazi Propaganda and the Myth of a “National Community”

The National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP or Nazi Party) was one of many radical right-wing political parties to emerge after World War I (1914–1918). From the very beginning, it was an antisemitic and racist organization. It also opposed the new German republic established after the German Revolution of November 1918. In its party program of 1920, the Nazi Party asserted that only a Volksgenosse (national comrade or member of the people) could be a citizen. A “national comrade” was defined as someone who was of “German blood,” regardless of religious denomination. As a result, no Jew could be either a “national comrade” or a citizen. The Nazis defined the Jewish people as a “foreign” racial group with origins in the Middle East. Thus, according to Nazi ideology, a Jew could never become a German. This was the case even if they spoke German, if they converted to Christianity, or if their family had lived in Germany for hundreds of years.

The Concept of “National Community” in the 1920s and Early 1930s

Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, the Nazi Party campaigned for the votes and support of millions of Germans. Its propagandists skillfully exploited the terms “national community” and “national comrade.” In the final years of the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), the Nazi Party dramatically increased its representation in the German parliament (Reichstag). In summer 1932, it became the largest political party represented there.

Nazi propagandists framed the party as a movement that aimed to restore national greatness and prosperity—one that theoretically represented all Germans regardless of class, region, or religion (Christian religion). Hitler often pointed out that the Nazi Party was a microcosm of the “national community” that he envisioned for the future. He maintained that the Nazi Party, because of its broad mass basis, served as the vanguard of the future German “national community.” This community would then, in turn, serve as the foundation of a Nazi state.

Nazi propagandists declared Nazism to be a movement that was open to all ethnic Germans. This idea won over many Germans who had become disillusioned with the status quo and the failure of the country’s leadership to solve the nation’s growing economic problems during the Great Depression. Hitler promised to restore social harmony by bringing together white and blue collar workers and eliminating class hatred and conflict. These appeals and the idea of returning Germany to greatness resonated with many.

On July 15, 1932, Hitler expressed this point in an election speech:

Thirteen years ago we National Socialists were mocked and derided—today our opponents’ laughter has turned to tears!

A faithful community of people has arisen which will gradually overcome the prejudice of class madness and the arrogance of rank. A faithful community of people which is resolved to take up the fight for the preservation of our race, not because it is made up of Bavarians or Prussians or men from Württemberg or Saxony; not because they are Catholics or Protestants, workers or civil servants, bourgeois or salaried workers, etc., but because all of them are Germans.

During their election campaigns, however, the Nazi Party never explained how the new “national community” was to be constructed and who would fully be a part of it. And at what cost.

The Third Reich: Persecution as a Building Block of a “National Community”

Once in power, the Nazi regime (which called itself the Third Reich) sought to fulfill its promise to create a “national community” for all ethnically and politically reliable Germans. Scholars debate whether or how far it succeeded in making this goal real. However, there is no doubt that it was an integral part of Nazi propaganda during the Third Reich. It was used to unify a divided nation by creating a sense of pride in membership, while at the same time promoting suspicion, fear, and/or hate of those who fell outside of it.

In Nazi Germany, groups such as Jews, Black people, and Roma and Sinti were defined as “racially alien.” Thus, they could not form part of the “national community.” They were disenfranchised and persecuted. Jews and Roma and Sinti were also later selected for annihilation.

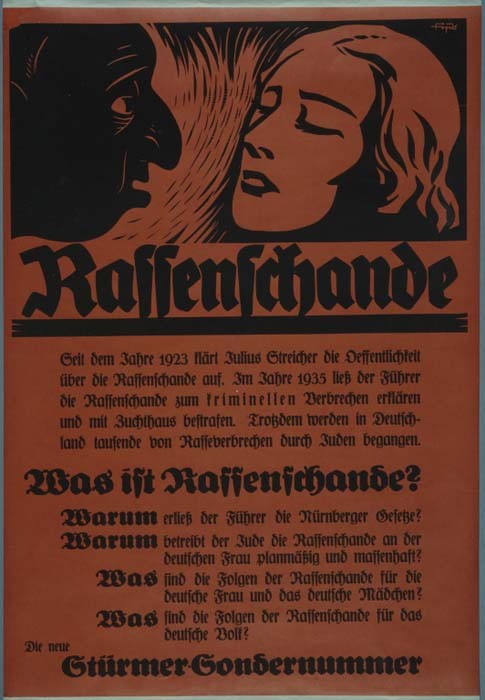

The Nazi regime also persecuted people because their political or social behavior did not fit into the new “national community.” It targeted political opponents, gay men, Jehovah’s Witnesses, “race defilers,” and others on these grounds. If a person was of ethnically German ancestry and altered their behavior, it was possible for them to be integrated into the “national community.”

Nazi policies and laws legalized “inequality” and justified the exclusion of various victim groups from membership in the “national community.” The Reich Citizenship Law of September 15, 1935, one of the Nuremberg Race Laws, spelled out who could or couldn’t be considered a citizen in the new Germany. Under the law, only a person of “German or related blood who proves through his behavior that he is willing and able to faithfully serve the German people and the Reich” could be a citizen. This clause made it clear that citizenship was not a right, but a privilege that was determined by the Nazi leadership. Subsequent ordinances specified that Jews, Black people, and Roma and Sinti would not be allowed to hold German citizenship.

Shifting Concepts of the “National Community”

Under the Nazi regime, the terms “national community” and “national comrade” were malleable concepts. Nazi leadership could manipulate these terms to exclude various people. Germans who continued to shop at Jewish stores or who maintained friendships with Jewish neighbors were denounced as “traitors to the people.” Germans abroad who expressed opposition to the regime often were deprived of their citizenship. Likewise, Nazi authorities launched public campaigns against those considered to be Gemeinschaftsfremde (aliens to the community).

In December 1937, the regime issued a decree on crime prevention. This decree was directed against individuals labeled as “asocial.” These persons were defined as people who, because of their anti-community behavior (even if it was not criminal), indicated that they did not want to be part of the community. Such a broad definition permitted the police to arrest and imprison some 100,000 persons. Among those arrested were those deemed to be “work shy,” vagrants, prostitutes, and beggars, as well as Roma and Sinti.

After 1938 and during the war years, Nazi rulers applied such policies to ethnic Germans. The regime did not consider all persons of German descent to be Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans), but only those who supported the policies of the new Germany. Individuals of German ancestry who continued to consider themselves Polish or Soviet citizens or who behaved in an “un-German” manner were not permitted to be a part of the “national community.” During World War II (1939–1945), hundreds of thousands of people of German ancestry were transferred by the SS from occupied territories in the Soviet Union and elsewhere to German-occupied Poland. The SS carried out racial and political screenings of the new arrivals.

The war also brought millions of non-Germans into the Reich as forced laborers. With millions of German men conscripted for military service, Nazi authorities feared that the influx of non-Germans, particularly Slavs, would negatively affect the racial and ethnic composition of the German population. German women who either had or were accused of having sexual relations with Polish, Soviet, and other foreign civilian forced laborers or prisoners of war were often publicly humiliated and deemed to be excluded from the “national community.” Sometimes, they were sent to concentration camps. The forced laborers often were imprisoned in concentration camps or executed.

Winning over Germans to the Volksgemeinschaft

While the Nazis never succeeded in creating a Volksgemeinschaft in reality, they created one in propaganda. Nazi propagandists were given instructions on how to properly stage events that would convey to participants that they were part of a “national community.”

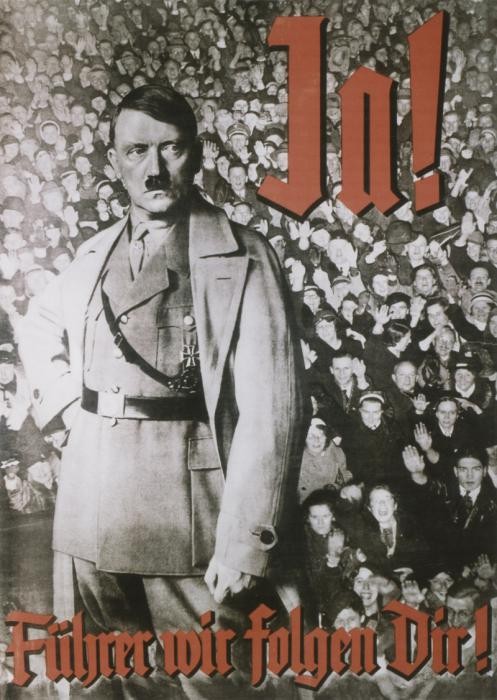

German filmmakers and photographers portrayed armies of Germans wildly cheering Adolf Hitler. This imagery gave credence to the “Hitler myth” and created an imaginary “national community.” Germans were encouraged and pressured to raise their arms in salute while saying the new German greeting, “Heil Hitler.” This effort aimed to convince Germans and foreigners that the entire nation stood behind the regime and its policies. Not participating called attention to the individual. It indicated that he or she did not feel themselves to be a part of the “national community.” Even if they did not fully support the government, Germans often engaged in such rituals in order to avoid public or police scrutiny.

In cinema and in newsreels, Nazi propagandists conveyed to the public that Germany stood behind the Führer. Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will exemplifies the Nazi staging of a “national community.” For example, the film contains cleverly manipulated shots of German Labor Service members calling out their home regions during the 1934 Nazi Party rally at Nuremberg. This aimed to show how Germans—regardless of their region, class, or religion—were united to build a new Germany.

Nazi propagandists also deployed other visual materials, such as posters. Imagery of happy German families conveyed a promising image of a healthy future. And posters depicting smiling factory workers aimed to convey social harmony and an end to class conflict.

Privilege and Inequality

The regime held out privileges to the population if they acted according to Nazi norms. Through the German Labor Front, it became possible for German workers to take vacations in and outside of Germany at reduced rates. Ship cruises to Norway and other locales were held out as potential perks. Hitler also promised to create an inexpensive automobile, the Volkswagen (the People’s Car), that would be affordable to many Germans who could drive on the country’s new highway system. Though many Germans invested money to purchase the new car, no one received one.

The propaganda of the “national community” masked glaring inequalities and persecution in Nazi Germany. The regime froze workers’ wages to the 1932 Depression era levels and increased work hours. Factory discipline increased and strikes were banned. Taxes increased. The availability of consumer goods, particularly those coming from abroad, was restricted. All Germans were expected to contribute funds to the government’s various relief campaigns. These funds were presented as individual sacrifices for the benefit of the community.

Impact of the "National Community"

Ultimately, Nazi efforts to create a “national community” aided in the persecution and systematic mass murder of individuals and groups who were excluded from membership. The Nazis aimed to incite hatred against Europe’s Jews and others they denounced as “enemies of the state.” They also helped to foster a climate of indifference to the suffering of others. Too many Germans found membership in a “national community” appealing and were willing to overlook or ignore the plight of the victims.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Max Domarus, ed., The Complete Hitler Speeches in English: A Digital Desktop Reference, trans. Mary Fran Golbert (Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1990), 145.