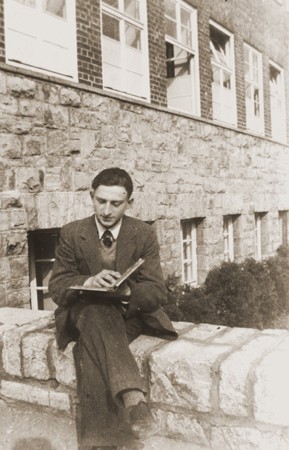

Jacob Wiener

“That night, they broke in, in the middle of the night, and they arrested all the boys, maybe 50 boys. It was a dormitory, in the middle of the night.” Listen to Jacob Wiener describe what happened to him during Kristallnacht. Learn more about his experiences during this wave of antisemitic violence in Nazi Germany in November 1938.

Audio

Transcript

Rabbi Jacob Wiener:

Me, personally, I was away from Bremen about 400 kilometers, in Würzburg, we were in Bavaria. That night, they broke in, in the middle of the night, and they arrested all the boys, maybe 50 boys. It was a dormitory, in the middle of the night.

Bill Benson:

Arrested all of you.

Rabbi Jacob Wiener:

Yes, and then they said, “Wait downstairs.” They came at 2:30 at night, and “Wait here.” We waited there and then afterwards they came and said, “Form lines outside, five abreast.” Now, Würzburg is a small city, it has cobblestones, and we were led through the streets.

In the meantime, from the morning to that time, they assembled as many as they could, people of the city, and they were staying at the side. And they walked us through the street, and while they were walking us through the street, these people, you see, called us names, they spit at us, and so forth.

We went through the streets and we went past the burning synagogues. Because–during that night, they burned about 400 synagogues I think, or so, in Germany. And we were led into the prison. When we came into the prison and the Nazis and Germans were very...special. They were very much interested in–meticulous. They were meticulous.

The first thing they asked us is, “Empty all your pockets,” and they took an inventory of that…

Bill Benson:

Of everything in your pockets.

Rabbi Jacob Wiener:

Everything, even if it was a penny, and then they led us into the cells. We were in the cells for about seven days. Every day, the cells got–people who were arrested there, many of them disappeared. They were sent to concentration camps. I was still there. When the seventh day came, after seven days, this was on the 9th of November—seven days later, the 16th, I think it was, Friday—in the evening, they said, “You stay out,” seven boys were standing out.

And then they said to us suddenly, “You are free. Go home to your hometown and report to the local Gestapo.” Gestapo means secret police. But I had no money and so forth, but making a long story short, I came home.

Bill Benson:

How did you get 400 kilometers with no money?

Rabbi Jacob Wiener:

There were miracles. I had many miracles. [Laughs.]

Bill Benson:

Somehow you got there.

Rabbi Jacob Wiener:

I met the secretary from the school. She gave me 20 marks. It was enough to take a train and go home. I came home—it was Thursday evening, and Friday morning, I came home. I called up my home, no answer. Then I took a streetcar, I went to my home, and I saw the windows of our business, as I said before, a bicycle business, were broken and barricaded.

I went to the other side. We had an entrance to the business and an entrance to the private quarters. There was a note: “Get the key from the police department.” Before I went to the police department, the non-Jewish neighbor of Papa’s who had a furniture business called me in.

He was afraid to come into the street. It was forbidden between Jewish and non-Jewish to talk to each other. But he called me in and he told me the story. That night, they had come in, broken the door, and told my brother to stand in the door and watch that no one should see it. They were afraid of [dark?].

Then they went up and in the meantime, my father had fled over the roof and he went to said to—he said to the neighbor, “I am going to Sweden.” During the war, there were only three countries which were neutral. They start all with an “S”—Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain.

So what happened is, he said, “I’m going to Sweden,” but they came into the house, broke in, and when they saw my mother, they asked her, “Where is your husband?” She didn’t want to, I don’t know, or she didn’t know what happened, and therefore, they killed her.

Biography

Koppel Gerd Zwienicki (later Rabbi Jacob Wiener) was born in Bremen, Germany, on March 25, 1917, to Josef and Selma Zwienicki. He was the eldest of four children. Josef ran a bicycle sales and repair shop and Selma worked as a kindergarten teacher and a bookkeeper for a large firm. As a child, Koppel, who went by “Gerd,” experienced the economic depression that followed World War I. He also witnessed the violent street fights between the Nazis and their political opponents, the Communists and Socialists.

Gerd was in high school when Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933 and the Nazi party came to power. Antisemitic laws were implemented as soon as Hitler took office. By April 1933 German law restricted the number of Jewish students in German schools and universities. Most of the teachers in Gerd’s school supported the new regime and incorporated “race science” courses into the curriculum. After high school, Gerd began rabbinical studies in Frankfurt am Main and later at the Jewish Teachers’ Seminary in Würzburg.

On November 9–10, 1938, Kristallnacht (often referred to in English as the “Night of Broken Glass”), a state-sponsored nationwide pogrom, Gerd was arrested and held for eight days in the Würzburg jail. Upon his return to Bremen, he learned that during Kristallnacht the Nazis shot and killed his mother and that his brother, Benno, had been sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Gerd traveled to Hamburg where he found his father and a younger brother.

After Kristallnacht, antisemitism grew worse. All Jews were prohibited from attending German schools and universities, cinemas, theatres, and sports facilities. In 1939 Gerd negotiated with the Gestapo (the German Secret State Police) and set up a school for Jewish children. Gerd’s father, Josef, had family in Saskatchewan, Canada, who were able to get papers that allowed the family to leave Germany. With the help of a man associated with the Cunard White Star Line (now Cunard Line), a British shipping company, Gerd and his family left Germany on May 31, 1939, and immigrated to Canada by way of Great Britain.

Gerd later immigrated to the United States on a student visa to attend the Baltimore Rabbinical College. In 1944 he was ordained as a rabbi and took a position at the Hebrew National Orphan Home in Yonkers, New York. He changed his name to Rabbi Jacob Wiener.

Rabbi Wiener earned a Ph.D. in Human Development and Social Relations from New York University and became a social worker for the New York City Department of Human Resource Administration after World War II. In 1948 he married Trudel Farntrog, a fellow survivor. Rabbi Wiener volunteered at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.