Les Milles Camp

Les Milles camp functioned as a French internment camp between the years of 1939 and 1942. It was founded under the leadership of the French Third Republic to intern enemy aliens during the Phony War, the name applied derisively to the first several months of World War II during which little fighting occurred in western Europe. In the Vichy era, Les Milles became a camp for foreign Jews awaiting emigration or, in most cases, deportation to German concentration camps and killing centers.

Key Facts

-

1

Between 1939 and 1942, 10,000 prisoners from 38 different nationalities were interned at Les Milles.

-

2

2,000 Jews interned at Les Milles were sent to Auschwitz.

-

3

Today, Les Milles serves in part as the headquarters for UNESCO’s Chair of Education for Citizenship, Human Sciences and Shared Memories. It is also a memorial open to visitors to better understand the experiences prisoners endured there.

Internment Camp

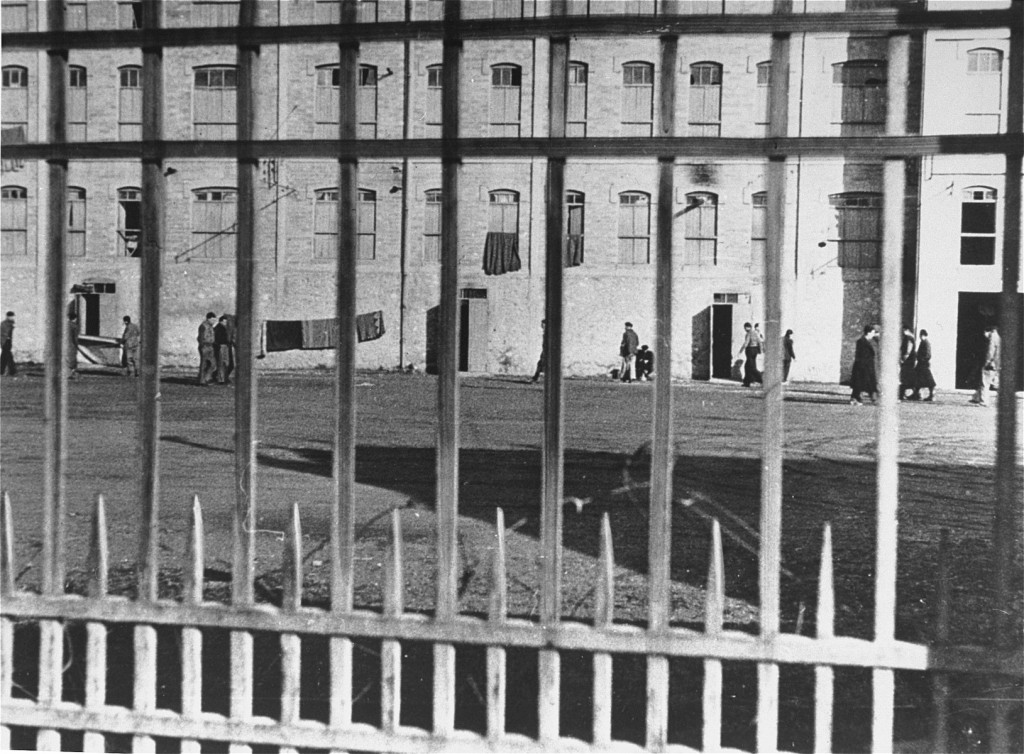

On September 5, 1939, French authorities released a list of “official enemies” of state requiring that they report to local assembly points. The directive targeted German and Austrian men ranging in ages from 17 to 50, including ex-nationals recently made stateless. At the various assembly points, local authorities rounded up the so-called “ressortissants ennemis” [enemy aliens] and sent them to internment camps around France. One such camp was Les Milles.

The French authorities rushed to transform Les Milles, a former tile factory in the south of France located between Aix-en-Provence and Marseille, into an enemy alien internment camp following the declaration of war on Germany. Many of those interned in Les Milles in the months leading up to the fall of the French Third Republic were in fact refugees who had fled the Third Reich due to Nazi anti-intellectual and antisemitic politics. Importantly, in the early days of the camp while under the authority of French army captain Charles Goruchon, discipline was relatively relaxed. Gourchon allowed the religious Jewish prisoners to pray in the camp’s central courtyard. Prisoners could even be assured release if they enlisted in the French army’s foreign battalion or as paramilitary workers.

Cultural Life in Les Milles

A vibrant intellectual and artistic community formed in the camp. Several famous German artists and intellectuals were interned in Les Milles in these early months including Hans Bellmer and Max Ernst. The artistic community created over 400 works of art as well as murals painted on the camp walls between 1939 and 1942. These works of art often depicted the conditions of internment. For example, Hans Bellmer incorporated bricks into many of his drawings, an allusion to Les Milles’s past as a tile factory and to his own incarceration. Max Ernst created a piece entitled “Les Apatrides” [The Stateless], a reference to the fact that many of those interned Les Milles at this time were stateless victims of Nazi persecution.

Many of these murals were painted in the guards’ dining room, frequently termed the “Murals Room.” The dominant painting there is a satiric “Last Supper,” with those at the banquet table wearing apparel from many nations and cultures, and eating the food associated with their countries. Such an international theme reflects the wide range of international prisoners. The mural is attributed to Karl Bodek who was subsequently murdered in Auschwitz.

Leon Feuchtwanger, a German Jewish writer, was also briefly interned in Les Milles. After his successful escape from war-torn Europe to America, he published a memoir of his time in Les Milles entitled The Devil in France (1941).

Prisoner Population

In April 1940, the camp population fell to 400 prisoners. The French authorities temporarily closed Les Milles, relocating the 400 remaining prisoners to the camp of Lambesc. Les Milles reopened the following month on May 19. The French government again ordered the arrest and internment of another 3,000 foreigners living in France, many of whom were sent to Les Milles. As the Germans continued to advance and the French war effort fell apart, French authorities transferred the 2,000 remaining prisoners at Les Milles to the Saint Nicolas camp near Nîmes. Following the signing of the armistice agreement on June 22, French authorities agreed to hand over any prisoners the German authorities demanded. The Germans sent these prisoners, several of whom had been interned in Les Milles, to Dachau. In June 1940, there were as many as 3,500 prisoners at Les Milles, resulting in overcrowding.

Transit Camp

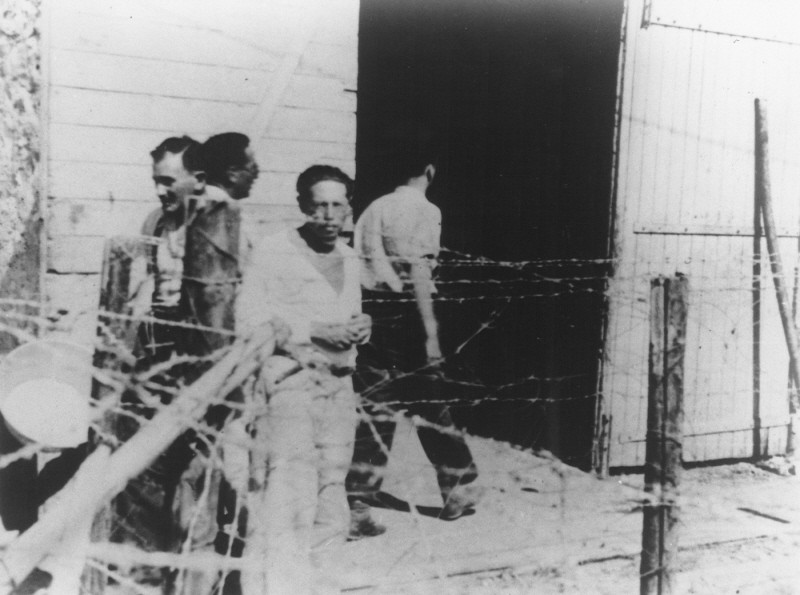

In October 1940, the collaborating Vichy government promulgated a law authorizing the internment of “étrangers de race juive” [foreigners of the Jewish race] in French camps. Les Milles accordingly transformed into a transit camp specifically for foreign Jews who intended to emigrate. In November 1940, the Vichy government ordered a branch of the French police force known as the gardes mobiles to take over responsibility for the administration of the camp from the French military. Robert Maulavé became the camp’s commandant. During this period, the gardes mobiles held foreign Jews in the camp under terrible conditions while they waited to emigrate. Ultimately, many waited in vain. Following July 1941, emigration became impossible.

As of November 1941, 1,365 prisoners inhabited Les Milles. Living conditions were cramped and sanitation was poor. External aid groups attempted to offer relief, given the lack of resources for prisoners. On October 9, 1941, Rabbi Langer, a representative from the Alliance israélite universelle (a Jewish international aid organization based in Paris), visited the camp and reported:

Outside, at the far end of the camp, a dozen pots spread out over makeshift fires are part of an effort to provide at least once a day a more or less decent meal to the most indigent internees, who, since they have no personal resources, would otherwise have nothing more than the food officially provided by the camp authorities.1

When André Jean-Faure, the Vichy camp inspector, visited Les Milles in October 1942, he too found the camp’s conditions to be deplorable. Camp authorities did not provide sufficient amounts of food; inmates received 100 to 200 grams of dried vegetables a day instead of the 600 grams they needed. Jean-Faure reported on the conditions: “Overcrowding had brought about the spread of lice and fleas. … This state of affairs was completely unacceptable.”2

In August 1942, the first round of deportations began in the unoccupied Southern Zone. As of August 3, French authorities locked down the camp of Les Milles. At this stage, it was still possible for Jewish parents to entrust their children to aid organizations. Seventy children between the ages of five and eighteen left Les Milles on August 10 for Hôtel Bompart. The following day, Vichy authorities deported the first convoy of Jews from Les Milles. In total, French authorities handed over more than 2,000 Jews interned in Les Milles to the Germans to be sent to Auschwitz. Approximately, 1,500 of these Jews arrived at Auschwitz via Drancy, a camp in the suburbs of Paris.

Closing of the Camp

On November 8, 1942, the Vichy government announced that they would no longer release exit visas. Les Milles, unable to serve its initial purpose as a way station for emigration, closed. The remaining prisoners in Les Milles were relocated to the camps of Gurs and Rivesaltes. Les Milles officially closed its doors in December 1942.

Commemoration

In 1982, the French government released plans to tear down the “Mural Room” in Les Milles camp. In response, CRIF (The Representative Council of French Jewish Institutions), the municipality of Aix-en-Provence, along with several survivors and resistance fighters, petitioned the government to save the room. They argued that the site was a historic monument. In 1985, these preliminary efforts resulted in the inauguration of a commemorative stone at the camp as well the creation of the Coordinating Committee for Safeguarding Les Milles Camp and a Memorial Museum of Deportation, Resistance, and Internment.

In 1990, the Coordinating Committee inaugurated the Chemin des Déportés [Path of the Deported] to honor the memory of those deported from Les Milles. Two years later, the Committee placed the Wagon du Souvenir [Remembrance Wagon] at the site where deportations took place. In 1993, the Committee worked to restore the Mural Room. In 2004, the French government named the entire camp of Les Milles a historic monument. Then, in 2009, French Prime Minister François Fillon inaugurated the Foundation of the Camp des Milles – Memory and Education to manage the monument.

In 2012, the Site-Mémorial du Camp des Milles opened to the public. It is the only French internment and deportation camp still intact today and open to the public. French Holocaust survivor and politician Simone Veil, on visiting the memorial site at Les Milles in 2012, reflected on the importance of having such places of memory:

It was with great emotion that I visited Les Milles Camp and contemplated the paintings, thinking about the suffering, but also the courage of those who painted them, before disappearing into the ‘Night and the Fog.’ We must remember them, preserve their last works, which are a message for us.3

Finally, in 2015, UNESCO chose Les Milles as headquarters for its new Chair of Education for Citizenship, Human Sciences and Shared Memories.

Critical Thinking Questions

What were the changing functions of the Les Milles camp?

To what degree was the French population aware of the camp, its purpose, and the conditions within? How would you being to research this question?

What can we learn from the art produced at Les Milles?

Did the outside world have any knowledge about these camps? If so, what, if any, actions were taken by other governments and their officials?

What choices do countries have to prevent, mediate, or end the mistreatment of imprisoned civilians in other nations?