Misuse of Holocaust Imagery Today: When Is It Antisemitism?

Many images and symbols from the Holocaust era have become easily recognizable. The familiarity of these visuals has also lent them to being misused in ways which distort the historical record, attack the memory of those whom the Germans and their collaborators murdered, and serve as a cover for prejudice and hatred.

Many images from the Holocaust era have become easily recognizable—whether symbols of Nazi propaganda (like the swastika) or physical objects or places that are now well known for their association with genocide (like barbed wire or the train tracks leading to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center). The ubiquity and currency of these visual icons reflects:

- The horror evoked by the crimes committed in the era of the Holocaust

- An enduring fascination with Nazi propaganda and imagery

- The diffusion of awareness about the Holocaust through educational efforts, mass media, and popular culture

Some of these visual images have come to serve as shorthand for the Holocaust itself or even evil more generally. The common understanding and familiarity of these images has also lent them to being misused in ways which distort the historical record, attack the memory of those whom the Germans and their collaborators murdered, and serve as a cover for prejudice and hatred.

Today, Holocaust-era symbols and images are frequently misused, including:

- To attack Jews or Jewish institutions

- To criticize the government of Israel by equating its actions to those of Nazi Germany or denying its legitimacy by saying that the Holocaust is a lie used to justify the existence of a modern Jewish state

- As epithets to symbolize ultimate evil, either to advance a political agenda or in situations of comparatively minor offense (e.g. labeling a cruel teacher a Nazi)

Some misuses reflect a conscious, informed attempt to attack and de-legitimize a specifically Jewish target. For example, a cartoon image equating the Gaza Strip with the Warsaw ghetto is an explicit effort to demonize Israeli policies and close off reasonable debate by equating the policies with Nazi genocidal ones. Similarly, a sign used at a public protest in Washington, DC, in March 2010, showed a distorted but recognizable version of the Israeli flag in which a swastika dripping with blood replaced the Star of David.

When individuals or governments misappropriate iconography of the Holocaust as a weapon against Jews or the Jewish state, they do so not merely with the intention of exploiting the pain of its memory, but also in the hope that such images will mobilize persons to their cause who are not themselves antisemitic. Holocaust imagery linked to Israeli policy also exploits older accusations of a Jewish conspiracy to control the world (such as in the antisemitic book The Protocols of the Elders of Zion) by suggesting that attention to the Holocaust is part of a sinister strategy to garner exceptional treatment for the Jewish state. Similarly, these visual linkages are akin to types of Holocaust denial which argue that the historical record has been distorted for material or political gain by Jews.

Many of these misappropriations of Holocaust imagery are calculated actions of Holocaust deniers or people with other antisemitic views. Some come from a misplaced naiveté—for example, a student scrawling a swastika on a school wall. The student may know that this is a Nazi symbol or simply that it is a forbidden one; his intention is likely more rebellious than antisemitic. The significance of such an act is radically different if a swastika and a Star of David are painted by a college student on the dormitory door of a Jewish student. This is a clear case of using a Holocaust-era symbol for a present-day hateful purpose.

The swastika has an extensive history and was used at least 5,000 years before the Nazis. It remains a sacred symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism, and other Asian religions and is a common sight on temples or houses in India or Indonesia. Swastikas also have an ancient history in Europe, appearing on artifacts from pre-Christian cultures. Despite its ancient origins, the symbol has become so widely associated with Nazi Germany that contemporary uses frequently incite controversy, whether or not they are intended as hateful visual statements.

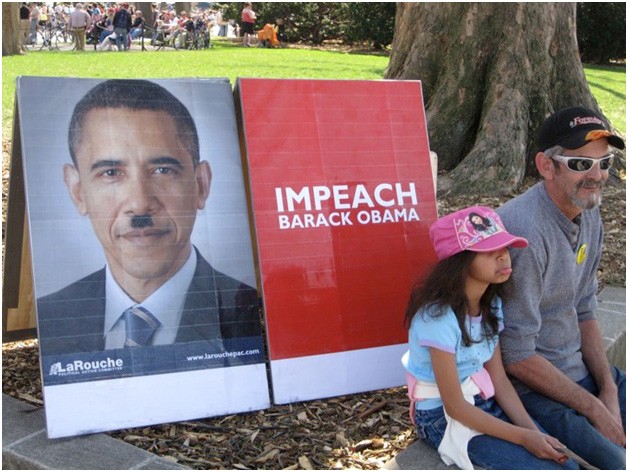

Not all misuses of Nazi imagery are directed at Jews. It is common to see such attacks mar political discourse in the United States. In a recent example, during public debate over healthcare reform there were frequent references to “death panels” with both subtle and overt comparisons between current proposals and the Nazi program of “euthanasia” or murder of the disabled. At many rallies, protestors waved signs depicting President Barack Obama with a small mustache in the style of Adolf Hitler. Similarly, opponents of legislation which would target illegal immigrants in the US have also likened such measures to those enacted in Nazi Germany. Holocaust images have also been adopted by animal-rights advocates who draw parallels between the Nazi genocide and factory farms in the United States.

In these, and many other cases, context matters. It is one thing to show antisemitic cartoons from the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer as part of an educational curriculum on the dangers of propaganda. It is another entirely when the same cartoons or ones that adopt similar visual analogies are used to attack opponents today. Those who co-opt recognizable icons of the Holocaust in the service of contemporary political causes simultaneously trivialize the memory of the murdered millions, and degrade the level of contemporary debate.

Critical Thinking Questions

How is the memory and history of the Holocaust used and appropriated today?

How might the misuse of the Holocaust imagery be harmful?

How can symbols, flags, and labels contribute to the rise of an ideology?