Supreme Court Decision on the Nuremberg Race Laws

The Supreme Court Decision on the Nuremberg Race Laws was one of a series of key decrees, legislative acts, and case law in the gradual process by which the Nazi leadership moved Germany from a democracy to a dictatorship.

Background

Supreme Court Decision on the Nuremberg Race Laws

December 9, 1936

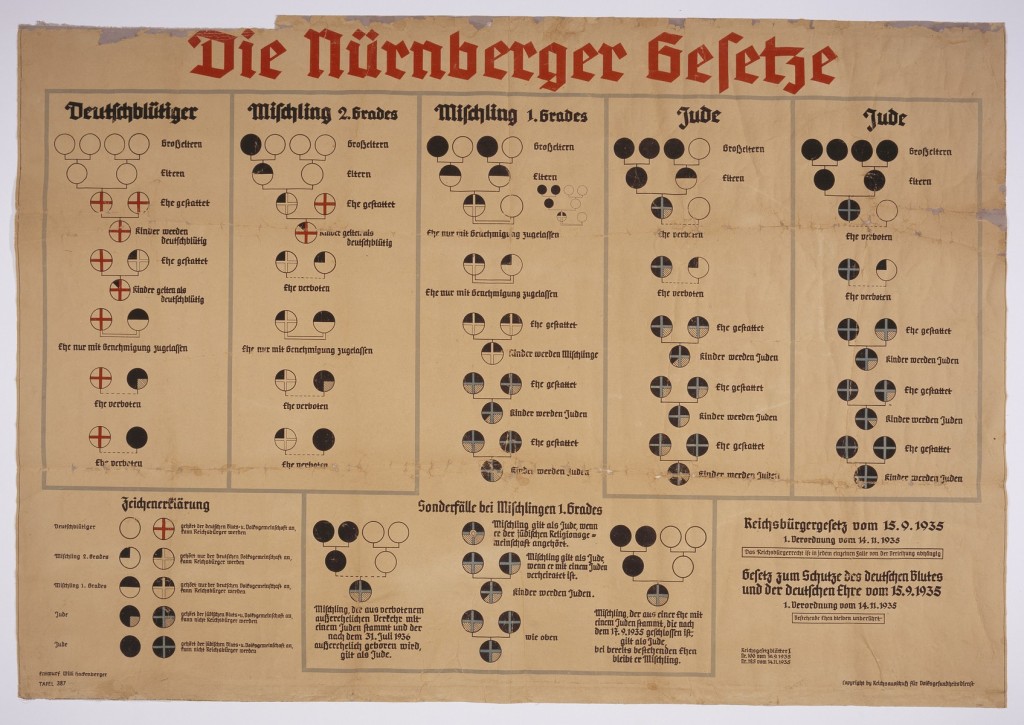

For the Nazis, the principle of the inequality of the races—and its legislative enactment in the form of the Nuremberg Race Laws and the decrees based upon them—applied to all areas of civil and criminal law. At the same time, they left it to the courts to provide practical guidelines for their implementation. It thus became the province of the Supreme Court to render final judgment on the interpretation of the law, since, as the highest appellate court in Germany, its decisions superseded those made by the lower courts. Indeed, the court eased the difficulties inherent in implementing anti-Jewish policies across a broad spectrum of cases from divorce to criminal race defilement. The court's acceptance and application of the race laws served an important propaganda purpose as well by explicitly conferring legitimacy on racial discrimination and persecution.

In November 1936, Erwin Bumke, president of the Supreme Court, indicated at a meeting of justice officials called to discuss the Nuremberg Race Laws that the court could accept the broadest interpretation of those laws put forth by Ministry of Justice State Secretary Dr. Roland Freisler. As Freisler put the matter, “The law…is a regulation that establishes the very foundation of the German people, which we do not seek to narrow but to broaden for the protection of our race.”

On December 9, 1936, the Supreme Court was given the opportunity to interpret the Nuremberg Race Laws when the Reich prosecutor requested that the court clarify precisely what was meant by “sexual relations” as it appeared in the law. While the court had previously interpreted the term to mean sexual intercourse or related acts, its landmark ruling broadened the meaning of “sexual intercourse” to include any natural or unnatural sexual act between members of the opposite sex in which sexual urges are in any way gratified. The court justified its ruling on the grounds that there would otherwise be almost insurmountable barriers to prosecution since sexual intercourse as such tended to take place among consenting adults and in private. Further, the court stated that since the law was intended to protect not only German blood but also German honor, an expansion of the definition of “sexual relations” was required. As a result, the court found that any act that satisfied a sexual urge violated the law; that the crime was established even if the sexual act occurred outside Germany; that intent was irrelevant in determining penalties; that a verbal proposition for sex violated the law; and, finally, that the crime did not require bodily contact.

In this ruling and in many that followed, the Supreme Court infused its decisions with Nazi ideology and expanded already outrageous laws that extended rather than limited the reach of Nazi authority. In so doing, the court bolstered the legal framework upon which the Nazi persecution of Jews was based and played a pivotal role in allowing the Holocaust to happen.

Translation

In the Name of the German People

(Translated from Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Record Group R22, File 50.)

The Great Senate for Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court in its session of December 9, 1936, in which the following participated:

The President of the Supreme Court Dr. Bumke as presiding judge

The Vice President of the Supreme Court Bruner

Senate President Dr. Witt

Justices Schmitz, Dr. Titel, Niethammer, Raestrup, Vogt, Dr. Hoffmann, Dr. Schultze

in the appeal of the State's Attorney under Article 137, Subsection 2, of the Court Organization Act has decided the following: The term “sexual relations” in the context of the Blood Protection Laws does not include every kind of illicit sexual action [Unzucht], but is also not restricted to sexual intercourse alone. It includes the entire range of natural and unnatural sexual relations that, in addition to sexual intercourse, include all other sexual activities with a member of the opposite sex that according to the nature of the activities are intended to serve as a substitute for sexual intercourse in satisfying the sexual needs of a partner.

Grounds:

The question of law, which is to be decided by the Great Senate under Article 137, Subsection 2, of the Court Organization Act upon the appeal of the State's Attorney for the First Criminal Senate [of the Supreme Court] in two pending cases, is posed as follows:

Whether the term “sexual relations” in the context of Article 11 of the first Ordinance for the Implementation of the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor of November 14, 1935 (Reichsgesetzblatt I, page 1334) is to be understood as referring only to intercourse, acts similar to intercourse, or all illicit sexual acts.

The requirement of Article 2 of the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, which forbids extramarital relations between Jews and citizens of German or related blood, is elaborated upon in Article 11 of the first Ordinance for the Implementation of the Law to the extent that extramarital relations as defined here means only sexual relations. What is to be understood by the term “sexual relations” is left for the courts to decide.

“Sexual relations” is not to be made equivalent to all illicit sexual acts. If the legislator had intended to encompass all illicit sexual acts in the prohibition then he would have chosen to include in the wording of the law the word Unzucht [illicit sexual acts], which has long had clear and specific definition in jurisprudence. The term Unzucht encompasses much broader, and even one-sided, acts of a sexual nature that by no means could be labeled “sexual relations.”

Additionally one has to look at the law as a whole in the interpretation of Article 2. The proscription against marriage (Article 1) and the proscription against employment (Article 3) clearly show that the intent of the legislator is to secure the maintenance of the purity of German blood through general proscriptions independent of the special circumstances involved in individual cases. The proscription against marriage is true even in those cases where both parties have ruled out the possibility of children resulting from the union; the proscription against employment is true even if in individual cases the Jewish member of a household, either because of age or illness, cannot be expected to make sexual advances. The comparison with these provisions leads to the conclusion that the provisions of Article 2 are valid not only in those cases involving extramarital sexual relations which result in pregnancy or which could have resulted in pregnancy.

Other difficulties argue against such a narrow definition equating “sexual relations” with “intercourse.” Such a definition would pose nearly insurmountable difficulties for the courts in obtaining evidence and force the discussion of the most delicate questions.

A wider interpretation is also required here because the provisions of the law serve not only to protect German blood but also to protect German honor. This requires that intercourse and such sexual activities-both actions and tolerations-between Jews and citizens of German or related blood that serve to satisfy the sexual urges of one party in a way other than through completion of intercourse be proscribed.

[Signed] Bumke Bruner Witt Schmitz Tittel

Niethammer Raestrup Vogt Hoffmann Schultze

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have affected the choices legal professionals made as the Nazi government consolidated its power in the 1930s?

What is the role of an independent judiciary in safeguarding democracy?