The Immigration of Refugee Children to the United States

Numerous organizations and individuals attempted to bring unaccompanied children, mostly German Jewish children, to the United States between 1933 and 1945. More than one thousand unaccompanied children escaped Nazi persecution by immigrating to the United States as part of these organized efforts. This article provides a summary of this work.

Key Facts

-

1

More than one thousand unaccompanied refugee children fleeing Nazi persecution arrived in the United States between 1933 and 1945.

-

2

Two organizations, German Jewish Children’s Aid and the US Committee for the Care of European Children, coordinated the largest efforts to bring children to the United States.

-

3

Officials in the US government proposed a few large-scale child immigration plans, including the 1939 Wagner-Rogers Bill and an attempt in 1942 to bring thousands of children from France, but these efforts were unsuccessful.

German Jewish Children’s Aid

After Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany in January 1933, American newspapers began to report extensively on Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews within its borders. In response to this news, concerned American Jewish groups founded German Jewish Children’s Aid (GJCA) in April 1934, an organization dedicated to coordinating the immigration of unaccompanied German Jewish children to the United States. Under the direction of social worker Cecilia Razovsky, GJCA placed these children, all of whom were sixteen or younger, with foster families or with American relatives.

GJCA worked with the Children’s Bureau that at the time was part of the US Department of Labor. The Children's Bureau granted the GJCA permission to bring the children to the United States on a corporate affidavit, rather than requiring that each child have an individual American financial sponsor. The Children’s Bureau also agreed to supervise and approve the foster homes. By July 1939, GJCA had brought 414 children to the United States, though their efforts were constantly hampered by a lack of adequate funding and the difficulty of finding suitable foster homes.

American Board of Guardians for Basque Refugee Children

In 1937, after the aerial attacks on the Basque towns of Guernica and Durango, prominent Americans, including Albert Einstein, Dorothy Thompson, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, formed the American Board of Guardians for Basque Refugee Children to help children escaping the Spanish Civil War. The group planned to bring 500 children to the United States for the duration of the war, and more than 3,000 American families volunteered to sponsor them. However, American Catholic groups expressed concern that the plan would be used as propaganda against the (largely Catholic) Nationalists in Spain, which had solicited its German and Italian allies to carry out the aerial strikes. Although more than 20,000 women and children found havens in other European countries, no unaccompanied Spanish refugee children came to the US during the Spanish Civil War.

Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus: "50 Children"

After the Nazi German regime annexed Austria in March 1938 and perpetrated Kristallnacht in November 1938, the Jewish fraternal organization Brith Sholom recruited a wealthy Philadelphia couple, Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus, to go to Vienna to rescue Jewish children. After gathering fifty individual affidavits—legal documents which guaranteed the children’s financial support—from friends, the Krauses traveled to Vienna in the spring of 1939. They interviewed families who were close to the top of the waiting list for a US immigration visa. With the assistance of Philadelphia physician Robert Schless who accompanied them, they chose fifty children from those families. US State Department officials in Berlin and Vienna aided the Krauses in obtaining passports and visas for all of the children. After the group arrived in the United States on June 3, 1939, the children were housed at the Brith Sholomville camp in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. The camp was supervised by the Krauses, who hired family members and German Jewish refugees to care for the children. Most of these children were reunited with their parents, who were able to immigrate before the United States entered World War II in late 1941. Others spent the war with foster families. The Krauses themselves cared for two children in their home.

Despite the Krauses’ success, other Jewish aid organizations, including the GJCA, were alarmed that they had sidestepped the bureaucratic processes that had been established in cooperation with the US government’s Children’s Bureau to keep the children safe. These organizations also resented the fact that Brith Sholom had raised $150,000 to provide for the fifty children, a sum which dwarfed the budgets of other organizations trying to help many more children. The Children’s Bureau investigated Brith Sholomville, ultimately concluding that the Krauses and the Brith Sholom organization were treating the children very well.

The Wagner-Rogers Bill

In December 1938, prominent child psychologist Marion Kenworthy asked Clarence Pickett, the director of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker relief organization, to help lead an interfaith effort to support legislation allowing European refugee children to immigrate to the United States. Pickett solicited friends who had previously advocated on behalf of Spanish refugee children and immediately began to lobby members of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration to support a child immigration bill. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt both supported the effort.

In February 1939, Democratic senator Robert Wagner of New York and Republican congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts sponsored identical bills in the US Senate and House of Representatives to admit 20,000 German refugee children under the age of fourteen over a two-year period. Representative John Dingell Sr. of Michigan also introduced an identical bill. These bills, collectively known as the Wagner-Rogers Bill, were written with the help of Pickett and his interfaith colleagues and specified that 10,000 children each fiscal year (1939 and 1940) could enter the United States without being counted against the existing immigration quota laws. Although the bill did not indicate that the majority of “German refugee children” would be Jewish children, the realities of the ongoing refugee crisis in Europe made this an obvious and understood fact.

The authors of the Wagner-Rogers Bill tried to prevent criticism by enlisting powerful allies. The American Federation of Labor supported the bill, agreeing that the children would not add to the nation’s existing unemployment problem. The Children’s Bureau planned to supervise the placement and care of the children. The Non-Sectarian Committee for German Refugee Children, headed by Pickett, promised that the children would be provided for with private donations.

Opponents of the bill wanted to decrease immigration to the United States overall and argued that charitable efforts should be directed to impoverished American children instead of refugee children. A January 1939 public opinion poll asked Americans whether they supported permitting “10,000 refugee children from Germany to be brought into this country and taken care of in American homes.” Only 26% of respondents favored this idea; 67% opposed it.

The Senate Committee on Immigration amended the bill to admit the 20,000 German refugee children and count them within the quota system. Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina, a vocal opponent of the bill, also proposed allowing the 20,000 children to enter in exchange for ending all quota immigration for a five-year period. Senator Wagner refused to accept either compromise and withdrew the bill from consideration. Neither the Senate nor the House committees ever put the Wagner-Rogers Bill to a vote.

Evacuating British Children

In May 1940, Nazi Germany invaded and quickly defeated Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and France. With Germany threatening Great Britain, the British Parliament sponsored a new organization, the Children’s Overseas Reception Board (CORB), to evacuate British children to British commonwealth countries (mainly Canada) and to the United States. Some American newspapers published articles estimating that more than 200,000 unaccompanied British children might come to the United States for the duration of the war. Full-page ads appeared in the New York Times calling for “mercy ships” to evacuate the children across the Atlantic Ocean, though American isolationists feared that an attack on one of those ships might force the United States to enter the war. Still, a June 1940 Gallup poll showed that 58% of Americans responded “yes” when asked, “Should the United States permit English and French women and children to come to this country to stay until the war is over?”

The first group of 138 British children arrived in the United States on August 20, 1940. The Children’s Bureau kept track of the children, who were cared for by relatives or by foster families. In addition to the CORB children, some companies and universities also sponsored groups of British children. For example, in Rochester, New York, Eastman Kodak employees cared for more than 150 British “Kodakids,” the children of Kodak factory employees near London. Yale University professors cared for the children of Oxford University professors. And Washington Post publisher Eugene Meyer housed an entire British nursery school on his farm in Virginia.

The CORB program, however, did not last long. On September 17, 1940, a German submarine attacked and sank the SS City of Benares in the middle of the Atlantic. The ship had been carrying several hundred refugees to Canada, including 90 British children traveling with the assistance of CORB. Soon after the attack, CORB shut down, having helped 848 British refugee children reach the United States.

The United States Committee for the Care of European Children

Sensing that public opinion was shifting in favor of admitting refugee children, Eleanor Roosevelt gathered a group of child refugee advocates in June 1940. The United States Committee for the Care of European Children (USCOM), formed after this meeting and vowed “to clear the way for the admission of children evacuated from war zones in large numbers,” and “to assure their proper care during their stay.”

USCOM’s mandate was to help all European children, regardless of nationality or religion. Like the GJCA, USCOM had a corporate affidavit, allowing the organization to avoid having to secure individual financial affidavits for each refugee child. USCOM worked with existing agencies, such as GJCA and the Children’s Bureau, to place and supervise the children in foster homes after they arrived.

Eleanor Roosevelt,the honorary president of USCOM, wrote in her “My Day” newspaper column, “I am thankful beyond words that it is going to be possible to do something for these European children.” Marshall Field III, heir to a Chicago department store chain and owner of the left-leaning PM newspaper published in New York City, served as the organization’s director.

USCOM Transports

In the summer of 1940, Martha Sharp, a relief worker with the Unitarian Service Committee (USC), proposed organizing a transport that would bring twenty-nine children in France to the United States. US Department of State officials approved visas for the children, though the group did not leave until December 1940 due to bureaucratic delays. The Unitarians, USCOM, and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) paid for transportation costs, and USCOM arranged for the children’s care after they arrived in the United States. Although most of the children were not Jewish, and some were traveling or reuniting with parents, Martha Sharp’s efforts served as a model for future USCOM transports which would largely consist of unaccompanied Jewish refugee children.

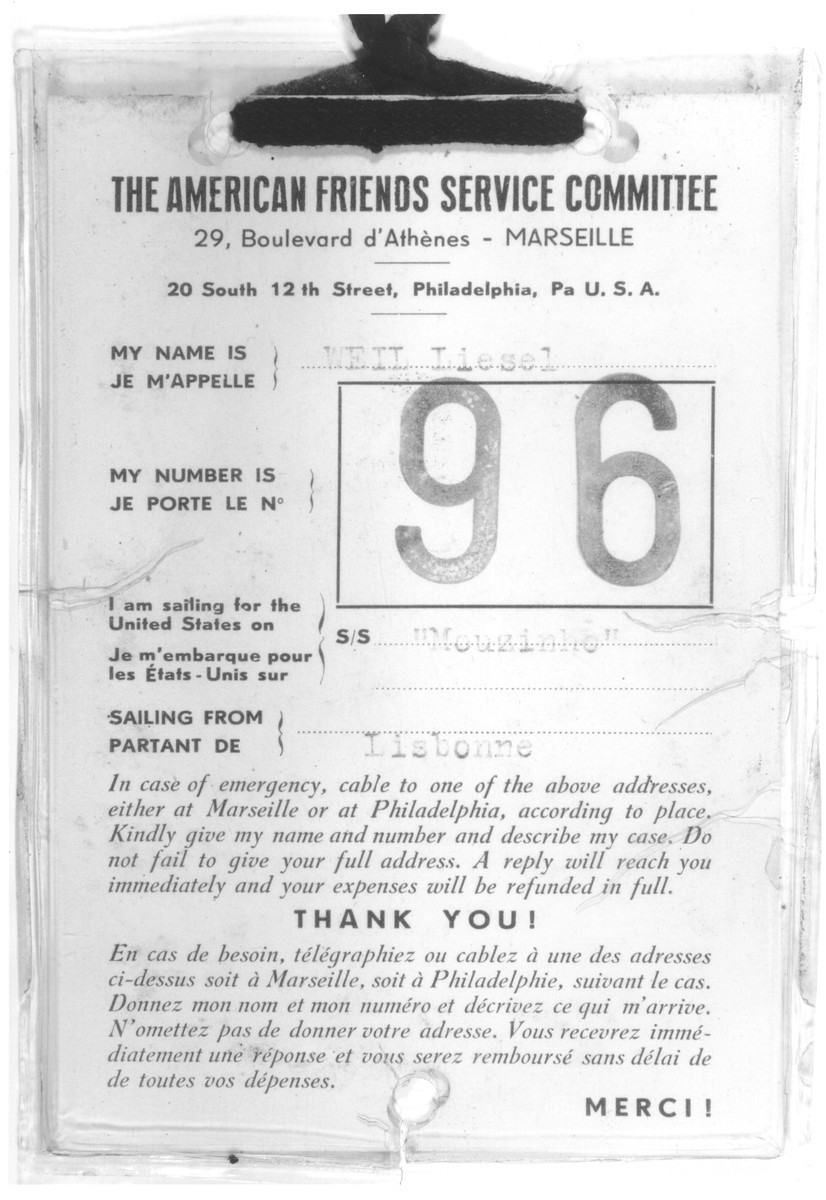

In early 1941, USCOM partnered with the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), the Quaker organization directed by Clarence Pickett, to arrange transports of refugee children. The AFSC had relief workers stationed in southern France and worked closely with other American relief groups and with the French children’s aid organization, Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE). AFSC workers selected the child refugees from children’s homes run by the OSE and by the Rothschild family, and from French internment camps.

Transport from Europe was difficult and expensive, and USCOM had to navigate Portuguese, Spanish, French, and American bureaucratic paperwork. Most of the children had to travel from France, through Spain, to reach Portugal, because the majority of the available passenger ships to the United States at that point left from Lisbon. Many American agencies became involved in the transports: the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee paid for tickets, with the assistance of HIAS and its European counterpart, known as HICEM. When the children reached the United States, they were cared for by GJCA and the Children’s Bureau, with the help of the National Refugee Service.

On Saturday, May 31, 1941, 100 children and their adult chaperones boarded a train in Marseille, France, to begin their journey to America. While still in France, at the train’s first stop, some of the children were able to see their parents, who were interned in the nearby Gurs internment camp, for the last time. The SS Mouzinho left Lisbon on June 10, arriving in New York Harbor eleven days later. A second group of forty-five children, also on the Mouzinho, arrived in New York on September 2, and third group of fifty-seven children disembarked from the SS Serpa Pinto on September 24, 1941. Each transport also included some children who were not officially part of the USCOM program, but traveled on these ships to reunite with relatives already in the United States.

Transports temporarily ceased after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, forcing the United States to enter World War II. The fourth USCOM transport, which arrived in New York on June 25, 1942, on the SS Serpa Pinto, left from Casablanca instead of Lisbon so that the children of Spanish Republicans, who would have been denied transit visas through Spain, could be included. A fifth transport, also from Casablanca, sailed on the SS Nyassa, arriving in Baltimore on July 30, 1942. In total, some 300 child refugees came to the US on these five USCOM transports and on Martha Sharp’s initial transport.

5,000 Children Plan

In the summer of 1942, Americans read reports of the July Vélodrome d'Hiver (or "Vél d'Hiv") mass arrest of Jews in Paris, including more than 3,600 children. In August, American relief workers and State Department officials witnessed Jews being arrested and deported from France in large numbers.

USCOM officials pressured the State Department to undertake a dramatic rescue effort, offering to bring 1,000 children to the United States as quickly as possible. The State Department approved the plan in mid-September, and soon after, President Roosevelt agreed to increase the number of children to 5,000. On October 23, 1942, French officials stated they would permit 500 children to leave, but only if there was no publicity in the United States about the effort.

The AFSC in Philadelphia gathered a group of relief workers, doctors, and nurses to assist in such a large movement of children. The day these aid workers sailed from Baltimore, November 8, 1942, Allied forces invaded North Africa. In retaliation, Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Vichy France, ending the possibility of any additional refugee children leaving France. US State Department officials, American journalists, and relief workers in southern France (including the AFSC staff living there) were arrested and interned in Baden-Baden, Germany. They were released as part of a prisoner exchange fifteen months later, in February 1944.

USCOM’s Wartime and Postwar Work

Although USCOM could no longer evacuate refugee children from southern France, the AFSC identified approximately eighty additional refugee children in Spain and Portugal, who were able to reach safety in the United States during the war.

As of March 1943, USCOM officials reported that their corporate affidavit covered 1,193 refugee children, including children who had arrived on USCOM transports and those who had come with the initial assistance of CORB. These children were living in foster homes in 65 cities across 35 US states; the group included 735 Protestants, 113 Catholics, and 320 Jewish children (the remainder were identified as “mixed”).

USCOM remained active throughout the war, both to support the children already in the United States and to be prepared in case any opportunity arose to rescue more. After the war, USCOM worked with displaced children, several thousand of whom were able to enter the United States after passage of the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. The organization ceased operations in 1953. In total, USCOM aided nearly 5,000 refugee children.

One Thousand Children, Inc.: Reuniting the Survivors in the 21st Century

In 2000, American researcher Iris Posner created the organization “One Thousand Children, Inc.” (OTC Inc.), an organization that represented and honored the experiences of unaccompanied refugee children and recognized them as Holocaust child survivors. Posner named this group of children the "One Thousand Children." Posner and OTC Inc. co-founder Lenore Moskowitz collected the names of approximately 1,400 refugee children who had come to the United States during the Nazi era, including the children who had been assisted by USCOM, the GJCA, and the Krauses. OTC Inc. sponsored reunions for these survivors and events at which they were able to share their stories. Though OTC Inc. did not exist during the 1930s and '40s, and the organization disbanded in 2013, it has given survivors who were unaccompanied child refugees a way to understand and share their experiences.

Critical Thinking Questions

What obstacles have individuals and organizations faced when considering the rescue of children in other endangered nations?

What factors might affect political leaders to open, limit, or block such efforts?