Wagner-Rogers Bill

The 1939 Wagner-Rogers Bill is the common name for two identical congressional bills: one in the US House of Representatives and one in the US Senate. The bills proposed admitting 20,000 German refugee children to the United States outside of immigration quotas. Despite congressional hearings and public debate in the spring of 1939, the bills never came to a vote.

Key Facts

-

1

The Wagner-Rogers Bill proposed admitting 20,000 refugee children from the Greater German Reich over a two-year period (1939–40). It did not become law.

-

2

During the 1930s, federal laws limited annual immigration to the United States. Many Americans supported these restrictive laws, known as “quotas.”

-

3

The debate in the US Congress and the American public regarding the Wagner-Rogers Bill mirrored a broader debate in the United States. Americans had different opinions about their responsibilities to help Jewish refugees fleeing persecution by Nazi Germany.

US Immigration Laws and the Refugee Crisis

During the 1920s, the US Congress passed laws that severely limited the number of immigrants who could enter the country each year. A series of restrictive legislative measures culminated with the Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act), which set quotas, or limits, on the number of immigrants from particular countries who could be admitted to the United States each year. Anti-immigrant sentiment, xenophobia, and antisemitism remained pervasive in the 1930s. These attitudes influenced the political, economic, and social climate as Americans responded to the refugee crisis caused by the Nazi regime.

This crisis for European Jews and others seeking to escape the Nazi regime’s persecution intensified in 1938. Germany annexed Austria (Anschluss) in March 1938 and the Sudetenland area of Czechoslovakia in September. On November 9 and 10, 1938, the Nazi regime unleashed a wave of violent anti-Jewish violence throughout Germany. This nationwide attack on Jews, known as Kristallnacht, saw the arrest of some 30,000 Jewish men and boys, some 26,000 of whom were imprisoned in concentration camps. They were released from concentration camps only after agreeing to leave Germany as soon as possible.

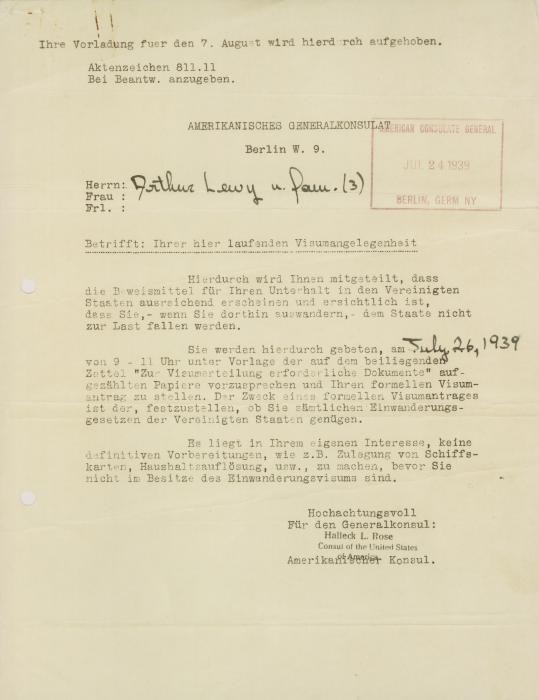

By 1938, hundreds of thousands of European Jews looked to the United States for refuge. Between July 1, 1938, and June 30, 1939, the US State Department granted the maximum number of immigration visas allowable (27,370) to German-born individuals. This marked the first time during the Nazi era that the German quota was filled. By mid-1939, some 309,782 German-born remained on the waiting list. To admit all of these refugees, the State Department would have had to issue the maximum number of visas allowable each year for more than 11 years.

Proposing the Bill

In December 1938, prominent child psychologist Marion Kenworthy asked Clarence Pickett, the director of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker relief organization, to help lead an interfaith, non-sectarian effort to support legislation allowing refugee children from Europe to immigrate. Pickett immediately began to lobby members of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration to support a child immigration bill. He succeeded in convincing Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

On February 9, 1939, Democratic senator Robert Wagner of New York and Republican congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts sponsored identical bills in the US Senate and House of Representatives. The bills were written by Pickett and his interfaith colleagues. They specified that 10,000 children under the age of fourteen would enter the United States for two fiscal years (1939 and 1940). The children would not be counted against the existing immigration quota. The bills did not indicate that the “German refugee children” would be mostly Jewish children. However, the realities of the refugee crisis in Europe made this an obvious and understood fact. The bills specified that when the refugee children reached the age of eighteen, they either would be counted against that year’s German immigration quota or would return to Europe.

Hoping for Success

The Wagner-Rogers Bill’s authors tried to anticipate and address criticism by enlisting powerful allies. The American Federation of Labor supported the bill, claiming that children would not add to the nation’s existing unemployment problem. The Children’s Bureau, an agency within the US Department of Labor, agreed to supervise the placement and care of the children. The Non-Sectarian Committee for German Refugee Children, headed by Pickett, promised that private donations would support the children.

For the first time in her six years as first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt allowed reporters to quote her in support of pending legislation. The First Lady referred to the ongoing Kindertransports, which brought German refugee children to Great Britain and western Europe. She said: “England, France, and the Scandinavian countries are taking their share of these children and I think we should.” She also referred to the bill as a “wise way to do a humanitarian act.” Despite his wife’s urging, President Roosevelt never publicly commented on the Wagner-Rogers Bill.

The leaders of American Jewish organizations rarely lobbied for the bill publicly. They may have been concerned that any attempt to prioritize aid for Jewish refugee children might spark increased antisemitism in the United States. Senator Wagner and Congresswoman Rogers, neither of whom were Jewish, emphasized that their bill would admit both German Jewish and Christian children. Opponents, however, branded the legislation as an effort to help Jewish refugee children primarily.

Opposition to the Bill

The House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization and the Senate Committee on Immigration held joint hearings on the Wagner-Rogers Bill in late April 1939. These initial hearings seemed to go well for the bill’s supporters, but opponents soon grew more vocal.

Democratic Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina actively opposed the Wagner-Rogers Bill. He gave multiple speeches against the bill on the Senate floor and asked constituents to voice their opposition. Reynolds warned that admitting refugees—even children—would increase unemployment. At this point, Reynolds already had introduced five separate proposals in Congress to limit immigration. One proposal would have banned all immigration either for ten years or until the unemployment rate dropped to historically low levels.

Senator Reynolds garnered support from the American Legion and the American Coalition of Patriotic Societies. These groups included members of the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. The groups officially supported a decrease in immigration to the United States overall. They advocated for charitable efforts to help poor American children instead of refugee children.

Public Opinion

The public debate on the Wagner-Rogers Bill mirrored a broader debate about Americans’ responsibilities to help Jewish refugees fleeing persecution by Nazi Germany.

In January 1939, weeks before the Wagner-Rogers Bill was introduced, a public opinion poll asked Americans a related question. Would they favor a proposal to “permit 10,000 refugee children from Germany to be brought into this country and taken care of in American homes?” Only 26% of respondents favored this idea; 67% opposed it.

Throughout the spring of 1939, letters to the editors of American newspapers revealed a wide variety of opinions about the bill. In the Baltimore Sun, members of the public debated the proposal through the lens of Christian ethics. One letter-writer claimed that Jesus would not discriminate against foreign children. The writer also argued that Jesus would “not take the bread from one starving child to feed another.” The director of the “Young Peoples’ Alliance” wrote to the Brooklyn Eagle to ask his fellow Americans “not to forget our glorious tradition. As far back as our Pilgrim Fathers we opened our arms to refugees for political and religious freedom.”

The Bill Is Defeated

In March 1939, members of the Non-Sectarian Committee for German Refugee Children informally polled US senators on the Wagner-Rogers Bill. Of the 45 senators who expressed their opinions, 21 favored the bill and 24 opposed it. Those who would not take a position indicated that the child refugee issue was “too hot to handle.”

By June, the bill appeared unlikely to be voted out of committee, a necessary step prior to a full Senate or House vote. Front-page news about the refugee ship St. Louis led anti-immigration activists to increase pressure on Congress to further restrict immigration, rather than to increase it.

The Senate Committee on Immigration proposed amending the bill to count the 20,000 German refugee children within the quota system. Senator Robert Reynolds proposed allowing the children to enter in exchange for ending all quota immigration for five years. Senator Wagner refused to accept either compromise, and he withdrew the bill from consideration. Neither the Senate nor the House committees ever put the Wagner-Rogers Bill to a vote.

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, beginning World War II. In June 1940, many members of the Non-Sectarian Committee for German Refugee Children became active in a new organization, the United States Committee for the Care of European Children (USCOM). USCOM first brought British children to the United States. It later secured passage for refugee children in France, Spain, and Portugal. Through USCOM’s efforts, several hundred refugee children were admitted to the United States during the war. This number was far less than the 20,000 children proposed by the Wagner-Rogers Bill.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have influenced the supporters of the legislation?

What pressures and motivations may have influenced the opponents?

Investigate how and why the support of and admittance of refugees has often been a topic of debate in various nations.