Life After the Holocaust: Blanka Rothschild

With the end of World War II and collapse of the Nazi regime, survivors of the Holocaust faced the daunting task of rebuilding their lives. With little in the way of financial resources and few, if any, surviving family members, most eventually emigrated from Europe to start their lives again. Between 1945 and 1952, more than 80,000 Holocaust survivors immigrated to the United States. Listen to Blanka Rothschild's story.

Life After the Holocaust was a project of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum to document the experiences of six Holocaust survivors whose journeys brought them to the United States. Their experiences reveal the complexity of starting over.

Blanka Rothschild, born Blanka Fischer, was born and raised in Lodz, Poland. As an only child she was especially close to her mother and grandmother. Her father died before the war broke out.

Listen to Blanka's Story

[caption=7b0ad1b7-f001-47ae-b758-376287bb5a5b] - [credit=7b0ad1b7-f001-47ae-b758-376287bb5a5b]

Transcript

Narrator: San Diego, California. It's Passover - a holiday that conjures up memories of another country and another time.

Blanka: My mother and father were ahm... non-observant Jews. However, the tradition was kept up. We went for all the big holidays to grandparents who kept the Judaism alive. And they were religious.They were not orthodox, but they were religious. I will never forget the Seders, the warm feeling of being with all my family - and with strangers. Because we always... My grandparents invited strangers. This was a tradition. From orphanage; soldiers who were of Jewish origin who did not have a place to go to. And they had a cook and a serving maid. And there was a long, long table laid in with this food. And the people and the happiness and the lights because my grandfather always said, "Let there be a lot of light, it's a holiday." So, all the lights in all the rooms were on. It was such a wonderful, happy feeling.

Narrator: Blanka Rothschild, nee Fischer, was born and raised in Lodz, Poland. As an only child she was especially close to her mother and grandmother. Her father died before the war broke out.

[Hitler's voice is heard, "Since 5:45am, we are returning fire." Crowd responds, "Heil!"]

Narrator: The Fischers were forced to move to the Lodz ghetto in the winter of 1939/1940.

[Goebbels' voice is heard, "I am asking you, do you want total war?" Ecstatic crowd, "Yes!" Marching is heard.]

Narrator: Four years later, the family was separated and Blanka was deported to Ravensbrueck, a concentration camp in Germany. After a few weeks, she was transferred to Wittenberg as a forced laborer in an airplane factory. It was here that a German supervisor beat Blanka so viciously that she suffered broken ribs and permanent spine damage. When the Allied Forces closed in on Wittenberg in April of 1945, the Germans deserted the camp and the women broke free. Propped up by friends and in spite of her pain, Blanka ran towards the advancing Russian army and into the line of fire.

Blanka: As a matter of fact, one of the girls was hit. Ahm - you just didn't have time to look! You were running. Like an animal. The first Russian was of Asiatic origin, because his face, the features were Asiatic. And he was very dirty. I remember his big black leather boots. Filthy uniform. He was the liberator. And we thought we should kiss his boots.

Narrator: They were given something to eat; salty, pickled herring.

Blanka: And, of course, we became very thirsty. There was no water. The pipes were broken. And they told us to leave. You have to understand the circumstances. The Russians were fighting. It was just unbelievable. I didn't see anything there of... of normal food ration or even lazarette, Red Cross. But they had some bandages. And they gave me the bandages, and I was bandaged around my body to hold my ribs.

Narrator: In the nearby fields, they met two Polish men, who had also survived as forced laborers. Together they continued their journey.

Blanka: My friends helped me. We reached the first house in the village. The roof was gone from the bombardment. We went to the basement. The basement was very well prepared with food and sleeping equipment. We lay down. We ate, we lay down and the very same night, two Russians came and raped two girls.

Narrator: Blanka escaped the same fate, because one of the Polish men covered her with blankets and sat down on top of her for the entire night.

Blanka: This was my liberation. Very bitter. I was petrified of the Russians now.

Narrator: Blanka moved into a nearby house, occupied by former French prisoners who agreed to protect her.

[Collage of radio announcements: British reporter, "This is V-Day in Germany." Churchill, "Victory of the cause of freedom." Stalin's voice over a Russian victory song.]

Narrator: On May 8th, the German forces surrendered. The war in Europe was officially over. However, the circumstances made it difficult to know where to go. After several weeks, Blanka decided to join a group of men and women who were walking to Poland.

Blanka: A human being is very strong, unbelievably strong...

Narrator: In search of family members, she made her way back to Lodz.

Blanka: And - our house was standing. And the so-called superintendent was still the same one. And when he saw me, he thought that he... that he saw a ghost! He said in Polish, "How come I survived? Why did I come back?" This was the greeting I received. When I wanted to go upstairs to our place, our apartment, a large place, the people wouldn't let me in.

Narrator: She went to the nearby offices of a Jewish aid organization, where lists were posted with the names of returning survivors. Only one name was familiar - that of a girlfriend who had survived the war in hiding with her husband. Blanka went to stay with the couple for two weeks, but didn't feel comfortable in Poland.

Blanka: I just didn't feel welcome. My - my Poland was not my Poland anymore. And, I decided to move to Berlin, because I was told that they had Displaced Person camps run by the Allied forces. And I thought maybe somebody survived there!

Narrator: Postwar Berlin had been temporarily divided among the Allied powers into four zones: American, Russian, French, and British. While the Displaced Persons camps, also known as DP camps, were under control of the military authorities, care of the DPs was primarily in the hands of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, known as UNRRA, and international refugee organizations. Blanka arrived by train, and made her way to the nearest camp, which was located in the Russian zone. Conditions were crowded and daily life regimented.

Blanka: We were given places to sleep. We were given food. And - ah, I was grateful for the help. But I didn't want this type of... I wanted privacy. And ah - I don't remember too much about it. Maybe because I'm getting older. Things are sort of slowly blending and disappearing. Ahm, I'm trying to remember the good things. And I'm trying to maybe subconsciously forget the sad things. Maybe this helped me to live.

Narrator: Early on, deliberate forgetfulness was a survival tool for Blanka. One memory she has tried to erase from her mind is the image of her emaciated, dying mother whom she found in the liberated concentration camp Sachsenhausen, near Berlin.

Blanka: And she was in Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen hospital, but she died. She was completely... (her voice trails off)... I saw her. I don't even want to think about it, because that's a terrible memory.

Narrator: Desperate for a semblance of normalcy, Blanka bribed a German policeman with the precious whole bean coffee she received from a Jewish relief organization. She wanted him to register her in the American zone, where officials might be able to locate her distant relatives in the US And he did. Again, she was moved into a DP camp. Again, it was a difficult experience.

Blanka: People were very enterprising. They were used to the conditions. They had friends. They were going to Poland. They were bringing goods back and forth to Breslau... Wrozlaw. I could not partake in any of this. And all to me was very strange. I couldn't eat the way people were... buying something, sitting at the table... and talking about business. I was lost! I didn't feel good! I wanted to be in a room of my own. I wanted privacy.

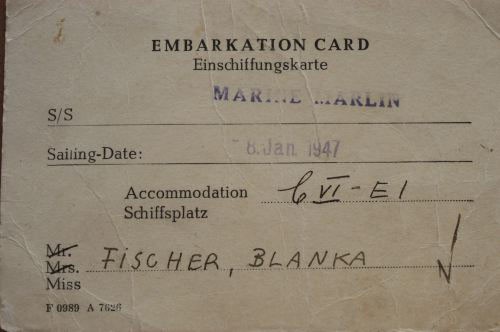

Narrator: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, one of the main agencies aiding Jewish DPs, helped locate Blanka's relatives in Detroit. In the winter of 1946/1947, Blanka crossed the Atlantic Ocean on the SS Marine Marlin, a troop transporter. The trip took over two weeks and was beset by storms and rough seas. The ship was damaged, and Blanka, who along with the other refugees was traveling in the lowest quarters, had to walk in water for days.

Blanka: When we arrived and we left the boat, we didn't go to Ellis Island. We went to a pier. There were benches, long benches. And there were letters above, alphabetically; A,B,C... And they told us to go to a letter that was corresponding with your last name. Since my name was Fischer, I went to letter "F." And I was sitting there. And people were coming and picking up their relatives or friends. And I was sitting and sitting and sitting... And, finally, I saw a gentleman, very distinguished looking gentleman walking by with a photo, ahm, showing that picture. And when I looked at the picture, I said in Polish, "This is my grandmother."

Narrator: It was the son-in-law of her grandmother's half-brother from New Jersey, who had come to pick her up. Her grandmother's sister in Detroit who had sponsored Blanka's emigration died one day before the steamer finally arrived. Since that family had a funeral to attend to, Blanka was to stay temporarily with her great-uncle.

Blanka: And we reached his place in ah - Paterson, New Jersey. It was Paterson. And his wife also spoke Polish and German and was the most wonderful, wonderful lady who made me feel good, warm. She hugged me. She kissed me. And that's what I needed. That's what I needed. I didn't need any material things. I just wanted to be loved, to belong. And that was the beginning.

Narrator: After the funeral, the relatives in Detroit invited Blanka to come and to stay. But she didn't find much warmth in this family, nor an understanding for the financial independence she craved. She got herself a menial job in the Polish section of town, saved the money, and returned to New Jersey, began training to become a baby nurse, worked hard to improve her English, and made new friends.

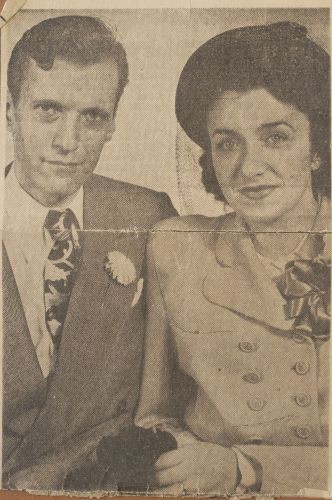

Blanka: What I wanted next was to have a child. I wanted to show Hitler that the seed survived. And I wanted a child the worst way. The doctors told me that it would worsen my condition. It would throw me off. But I felt that it was worth it. Ahm, I had - some ribs were damaged... broken. And the spine... It didn't show when I was clothed, in clothes. But when I was undressed, you could see sticking parts of it... And I was very self-conscious about it. It was very unconventional in those days to have a child without a husband. I got married to a man who is a very nice man. We both are of the same religion. We are both very honest. We are both civically minded people. We both love music, different kinds of music, but music. But we are very different. We are very different people, intellectually. I got married and I immediately, the next month, I got pregnant. I wanted it. And I wanted a daughter, because I always felt that a daughter will be close... closer than a son. So, I was lucky because I do have a daughter who is very close to me and we are very fortunate. We nourish each other. From the very beginning on, my entire life centered around this child. I lived on a fourth floor walk-up apartment in the Bronx. I had only one bedroom. And the bedroom belonged to her. We had a convertible in the living room. I tried to dress her the best I could. I tried to read stories, sing songs, teach her, expose her to music... I - I delighted in bringing her up. It was... my life changed. I was very grateful. When the baby was born, I used to... It was hot. We didn't have air conditioning. New York can be very cruel in the summer - the humidity. And we walked to the park at night. Nobody was afraid. It was a local park. And all the other mothers with their babies were there. And we were sitting at night not being afraid. So, we formed very close friendships. Not one of my friends there was a survivor, strangely enough. One was Italian. Conny, adorable. And three others were Jewish. We played mah-jongg, I remember.

Narrator: Her husband, an inspector for General Dynamics, made a modest living.

Blanka: If you don't have much and your friends don't have much, you're not unhappy. You have food. You have clothes. You - As a matter of fact, we were - when we played - once a week, we used to put, I don't remember, 50 cents or 75 cents on the side. When we had enough money, all the couples went to the theater, because we loved theater. Ahm - financially, I was not in a position to - to do things that I would have liked to. I would have liked to go to a good university. I thought that I had enough brain to do it. But my health was precarious.

Narrator: And still is. For many years now, Blanka has had to wear a full body brace, living in constant pain. But her motivation to give something back to the country that had adopted her, made her an active volunteer, pushing a library cart through a hospital, and helping teachers in her daughter's school. Blanka's daughter Shelley remained the center of her life. And Blanka made sure that Shelley was allowed to pursue her educational ambitions, a Master's degree in Shakespearean literature.

Blanka: My husband used to laugh. He said, "What you will do with Shakespeare?" He said, "How about a little typing on the side?" And she said, "But I love it!" So, I said, "Well, she loves it - so she has to do it. She has to be happy, to do what she likes to do." And we sent her to England to Shakespearean Institute. And - whatever you learn, it's your gain. It's a wonderful thing.

Narrator: In the mid-1970s, when children of survivors began to form groups in which they could share their experiences and support one another as members of the "Second Generation," Shelley did not join.

Blanka: I asked her about it. She said, she lives with it. Seeing my body it reminds her enough of Holocaust. She could not associate with a group and speaking about it. It hurt her too much. She always knew that I was a survivor. Her father was not. But I was a survivor, and I never made a - ahm, secret out of it. I did not tell her in the details, the gory details of what went through. I didn't want to go overboard. Because this was a child. I didn't want to poison her mind. I had to find the middle road for her to grow up to be a bright, open-minded person. But I wanted her to know because this was the legacy! She was entitled to know where her mother came from, my background. I wanted her to be proud of it, which she is. At the same token she resented the people who caused my... my affliction, my being disabled as a result of the tremendous beatings that I was getting. She could not accept it. And I tried to temper her dislike - more than dislike, her hatred into ahm... into understanding that people are people. There were people who were good.

Narrator: Blanka began speaking about her wartime experiences in the early 1970s. Out of a strong sense of obligation to those who perished, and in response to a general public which was now more interested in the Holocaust than it had been in previous decades.

Blanka: I am there on one purpose only, to tell people, oh not my personal story but to spread my message. And my message always was one "Let's tolerate one another. Let's learn about each other." And I always say that, "People, take this with a grain of salt. You don't have to love one another, but tolerate one another. Learn how to live together." The population is growing fast. The earth is getting smaller. We're flying from one place to another in few hours. If we won't learn how to get along, we will perish!

Narrator: First, she spoke to American-born friends, women's groups and churches in San Diego, where she now lives. Then in state schools and universities. But she pays a price.

Blanka: The price is - my health. My innermost feelings... my... my dreams... my nightmares. But you have to decide is it worth it? I lived with a sense of guilt all my life. I felt that maybe I wasn't the one deserving to survive. Maybe I wasn't worth it. There were so many people in the family who were much more deserving to survive, and I was chosen to be the one. You live with this guilt always. So, old age is... it's not so sweet. The only sweetness is the family. My granddaughter's name is Alexis Danielle. She was born in 1978. She's the joy of all our lives. She's beautiful in and out. She's bright. She is in her first year of law school, wants to study environmental law. Her parents are very, loyal wonderful couple. I was very lucky that my daughter married a man who's a wonderful husband and father, and provides cultural background. They do go to theater... Alexis is very well rounded young person, as is my daughter. I believe in some sort of Supreme Being, but I couldn't define it. I did not have Hebrew education. Neither did my mother. Ah... I, I'm an extremely good Jew at heart, because I believe in the commandments... And if you follow the commandments, you're religious. Ahm - my father's idea was more philosophical. He thought that God surrounds us. That God is everywhere, in every human, in every living tree, in the nature. And ah - I sort of adopted this. However, in camp I was questioning, "Where is this supreme being, where is God, what's happening?" These are human beings who are doing this to other human beings. Therefore, is there a God? The questioning - long time. I slowly returned to the faith. I'm not a temple goer, but I feel that I'm a good Jew, because I observe the commandments. I will not steal. I will honor - unfortunately, I don't have parents, I'm an old lady myself. And ah I tried to bring up my daughter in this spirit. And my daughter did not have bat mitzvah, but my granddaughter did. So, it's like coming back. The circle is repeating.

Narrator: Six years of war life; over fifty years of postwar life...

Blanka: They are two different lives. There is no comparison. There is nothing that I can say - I can weigh one against the other. The six years of imprisonment were - German word "Ewigkeit," "eternity." These years now - especially now that I grow older - passing by very quickly, too quickly. I want to live long enough to see my granddaughter graduate. To see good things. To see her get married, and then I will be completely happy. To hear from people again, "I have listened to you and I appreciate it. I learned something from you." That would be wonderful. It would be something... fulfillment.

Credits

Narrator: This program is part of "After the Holocaust", a series of audio profiles of Holocaust survivors in America. It was conceived and written by Regine Beyer and Arwen Donahue.

Studio production by Regine Beyer with Helen Thorington, engineer, at the New Radio and Performing Arts studio in Staten Island, New York.

The narrator was Jane Altman.

Special thanks go to the German Radio Archives, DRA, in Potsdam-Babelsberg; to Belgian producer Ronny Pringels and to German producer Helmut Kopetzky for the use of sounds from their archives.

"After the Holocaust" is a production of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The interviews in this program were conducted for the Oral History Department of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, with financial support by the Jeff and Toby Herr Grant.

The Museum gratefully acknowledges Jeff and Toby Herr for making these interviews and this audio series possible.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What challenges faced survivors of the Holocaust?

- How did various countries respond to the plight of survivors?