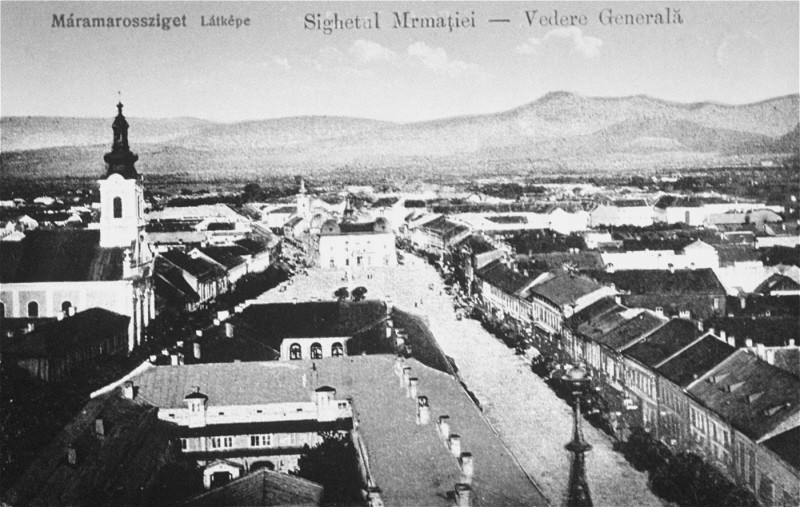

Sighet

Sighet (known today as Sighetu Marmatiei), a town in Transylvania, was part of Romania following World War I. The town was part of Hungary between 1940 and 1944. Sighet is well known as the birthplace of Elie Wiesel (1928-2016) noted Holocaust survivor and author of Night. Wiesel, his family, and the rest of the Jews of Sighet were deported from the town to Auschwitz in May 1944.

Key Facts

-

1

Sighet is the birthplace of noted Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel (founding chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize).

-

2

A ghetto was established in Sighet on April 18–20, 1944, after the German occupation of Hungary. Approximately 14,000 Jews from Sighet and surrounding villages were crowded into the ghetto.

-

3

The entire Jewish population of Sighet was deported to Auschwitz from May 17–21, 1944. Most of the deportees were gassed on arrival.

The Jewish Community of Sighet

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Sighet was the capital of Máramaros County in the Kingdom of Hungary. Following World War I, when northern Transylvania was returned to Romania, Sighet became part of Romania. During World War II, the town was again part of Hungary between 1940 and 1944.

Population

A significant Jewish population in the city can be traced to the early 18th century, when there were approximately 100 Jews living in the town. Over the course of the 19th century, the Jewish population of Sighet grew, reaching close to 8,000 Jews on the eve of World War I (roughly 37% of the town's population). Nearly 10,500 Jews lived in Sighet at the start of World War II.

Religion

Sighet was located in a geographically isolated region surrounded by the Carpathian Mountains where the forces of modernization were slow to arrive. Culturally and economically, the Jews in Sighet and Mármaros County resembled the Jewish populations of many shtetls in eastern Europe, where religious Orthodoxy and Hasidism predominated.

Among the main Hasidic sects were followers of Rabbi Yekuti'el Yehudah (1912–1944) Teitelbaum and later his uncle Yoel Teitelbaum (leader of Satmar Hasidism); followers of the Vizhnitser rebbe, whose Hasidim continued to dominate most of Máramaros County; and followers of new Hasidic dynasties such as Spinka, founded by Yosef Me'ir Weiss, and Kretchnev (a Nadwórna offshoot), founded by Me'ir Rosenbaum.

In addition to Hasidic groups, members of Zionist youth movements and followers of Religious Zionism also populated the town.

Economy

By the late 19th century, once it became possible for Jews to own land and timber, many Jews worked in the lumber industry. Sighet, with its sawmills, became a center in the forestry business. The town also functioned as a center for salt trade from nearby salt mines.

Sighet under Hungarian Rule

In 1940, Hungary annexed northern Transylvania from Romania. This followed an agreement between Romania and Hungary, arbitrated by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy and known as the Second Vienna Award. After the annexation, Sighet (part of Transylvania) was once again under Hungarian rule. In 1941, 10,441 Jews lived in Sighet.

In the summer of 1941, Hungarian authorities rounded up approximately 20,000 Jews who had not been able to acquire Hungarian citizenship, and deported them to Kamenets-Podolsk in German-occupied Ukraine. This deportation was described by Elie Wiesel in Night through the experience of Moishe the Beadle (caretaker of a synagogue):

“And then, one day all the foreign Jews were expelled from Sighet. And Moshe the Beadle was a foreigner. Crammed into cattle cars by the Hungarian Police, they cried silently. Standing on the station platform, we too were crying. The train disappeared over the horizon; all that was left was thick, dirty smoke…”

In Kamenets-Podolsk, Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing units) massacred approximately 23,600 Jews on August 27–28, 1941, described as the first large-scale massacre of the “Final Solution.”

According to historian Randolph Braham, approximately 2,000 Jews escaped and slipped back into Hungary in various ways. Among them was Moishe the Beadle. As described by Wiesel, Moishe the Beadle attempted to inform the Jews of Sighet of what he had witnessed, “but people not only refused to believe his tales, they refused to listen.”

After the deportation of August 1941, life gradually returned to normal for the Jews of Sighet and Máramaros under the rule of Hungarian prime minster, Miklos Kallay. Kallay refused to deport the Hungarian Jews despite German pressure to do so.

Even in this “quiet period,” however, the Hungarian government enacted antisemitic laws similar to those in effect in Nazi Germany. Tens of thousands of Jews from the Máramaros region were still drafted into Hungarian forced labor battalions. Approximately 40,000 Hungarian Jewish forced laborers died on the eastern front, in the Ukrainian Steppes.

Sighet after the German Occupation of Hungary

Hungarian Admiral Miklos Horthy and Prime Minister Kallay recognized that Germany was increasingly likely to lose the war following significant setbacks on the eastern front in 1943. Kallay attempted to negotiate a separate armistice with the Western Allies. To prevent this, German forces occupied Hungary on March 19, 1944. The Germans allowed Horthy to remain in power if he would remove Kallay and appoint a new government.

The new prime minister, General Dome Sztojay, committed Hungary to remaining in the war effort. He cooperated with the Germans in the deportation of Hungarian Jewry. Within six weeks, the Jews of Sighet and the rest of the Jewish communities in Hungary outside Budapest were concentrated in ghettos. (The Budapest ghetto was created later, in November 1944.)

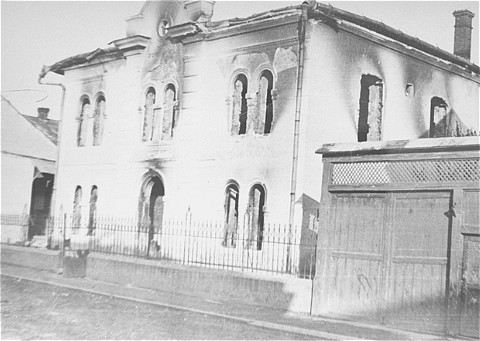

The Sighet ghetto was established on April 18–20, 1944. It contained two sections: a large ghetto within the city, which consisted of four streets where the Jews lived; and a small ghetto established in the slum-suburb “Ober-Yarash,” containing several tiny alleys. Jews from rural areas who had previously been held in the Berbest ghetto were placed in Sighet's small ghetto.

In the large ghetto, where Elie Wiesel and his family lived, 11,000 Jews from the city itself and a few nearby villages were concentrated. The smaller ghetto contained about 3,000 Jews.

Conditions in the Sighet Ghetto

The Sighet ghetto was extremely crowded. Living conditions were appalling. Jews were forced to abide by various edicts. They had to turn over valuables to the authorities on punishment of death. They were forced to wear a yellow star and forbidden to leave their homes in the evening under a curfew imposed in the ghetto.

The ghetto was guarded by the local police and 50 police officers brought in from Miskolc. The commander of the police, Colonel Sárvári, and others, tortured Jews into confessing where they had hidden their valuables.

Internally, the ghetto was administrated by a Zsidó Tanács (Jewish council), headed by Rabbi Samu Danzig.

Deportations from Sighet

At the end of April 1944, a delegation planning the destruction of Hungarian Jewry visited the ghetto. The delegation was headed by Adolf Eichmann on the German side and Laszlo Endre on the Hungarian side. They were accompanied by employees of the Ministry of the Interior and medical professionals.

Deportations from the two sections of the Sighet ghetto were carried out in four stages. The first took place on May 17, 1944, from the small ghetto, "Ober-Yarash. Deportations from the larger Sighet ghetto followed on May 18, 19, and 21, 1944. The residents of the larger section were transferred to the smaller location of “Ober-Yarash” and from there, deported to Auschwitz. These were among the first deportations from any ghetto in Hungary.

Wiesel described his family's last Sabbath in Sighet, the day before their deportation from the town forever:

The synagogue resembled a large railroad station: baggage and tears. The altar was shattered, the wall coverings shredded, the walls themselves bare. There were so many of us, we could hardly breathe. The twenty-four hours we spent there were horrendous. The men were downstairs, the women upstairs. It was Saturday — the Sabbath — and it was as though we were there to attend services. Forbidden to go outside, people relieved themselves in a corner.

The next morning, we walked toward the station, where a convoy of cattle cars was waiting. The Hungarian police made us climb into cars, eighty persons in each one. They handed us some bread, a few pails of water. They checked the bars on the windows to make sure they would not come loose. The cars were sealed. One person was placed in charge of every car: if someone managed to escape, that person would be shot.

Two Gestapo officers strolled down the length of the platform. They were all smiles; all things considered, it had gone very smoothly.

In less than two months, between May 15 and July 9, 1944, nearly 440,000 Jews (most of the Hungarian Jewish population outside of Budapest) were sent to Auschwitz. Most were gassed on arrival at Birkenau.

Elie Wiesel's mother, Sarah, and his younger sister, Tzipora, were among those sent to the gas chamber. His older sisters, Hilda and Beatrice, who were separated from the rest of the family, managed to survive. Wiesel and his father, Shlomo, stayed together, surviving forced labor and a death march to the Buchenwald concentration camp, near Weimar in Germany. Shlomo died in Buchenwald in January 1945, three months before the camp was liberated on April 11, 1945 by the 6th Armored Division of the US Army.

After the Holocaust

Of the nearly 14,000 Jews deported from Sighet in May 1944, it is estimated that only several hundred survived after the war. In 1947, Sighet had 2,308 Jews, including some survivors and a considerable number of Jews who settled there from other parts of Romania. Most would eventually resettle in Israel or other parts of the Jewish world.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

Wiesel, Elie. Night. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006, p. 6.

-

Footnote reference2.

Wiesel, Elie. Night. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006, p. 22.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations may have influenced the actions of the local population?

How can societies, communities, and individuals reinforce and strengthen the willingness to stand up for others?

Learn about the lives of the Jews in the community of Sighet before 1939.

Read Night by Elie Wiesel. How does the author portray the town and its inhabitants?