The Holocaust in Hungary

During the Holocaust (1933–1945), the Hungarian government persecuted and murdered Jews on its own initiative and in collaboration with Nazi German authorities. The Holocaust in Hungary affected Jewish communities both within the country and in its annexed territories in central and eastern Europe. In total, some 825,000 Jews were under Hungarian control during World War II. About 550,000 of them were killed in the Holocaust.

Key Facts

-

1

The timing of the Holocaust in Hungary in 1944 set the stage for a devastating increase in mass murder. It also led to extraordinary rescue efforts.

-

2

From 1938 to March 1944, the Hungarian government enacted anti-Jewish laws and policies on its own. Between 44,000 and 63,000 Jews were killed as a result of Hungarian actions in this period. This was the first stage of the Holocaust in Hungary.

-

3

In 1944–1945, German and Hungarian authorities worked together. In just one year, they murdered about 500,000 Jews from Hungary. This was the second stage of the Holocaust in Hungary.

Hungarian Jews were the last major Jewish population to fall under Nazi control.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Hungary’s Jewish population experienced persecution and violence at the hands of the Hungarian government. But it was not until spring 1944—more than four years into World War II—that they faced the full force of the Nazi killing machine. By this time, the Nazis had honed the violent processes of discrimination, dehumanization, and deportation now known as the Holocaust (1933–1945). They had already murdered millions of European Jews.

The timing of the Holocaust in Hungary set the stage for a devastating increase in mass murder. The Nazis and their Hungarian collaborators murdered approximately 550,000 Jews living in Hungary during the Holocaust. The vast majority of these victims—about 500,000—were killed in the last year of the war. Many were murdered in the gas chambers of the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center. Photographs of the arrival of Jews from Hungary at Auschwitz have become iconic images of the Holocaust.

The timing of the Holocaust in Hungary also set the stage for extraordinary rescue efforts. The most famous is the international rescue operation led by Raoul Wallenberg. Approximately 250,000 Jews from Hungarian-controlled territories survived the Holocaust. Among these survivors were Livia Bitton-Jackson, the author of I Have Lived a Thousand Years, and Nobel Prize laureate Elie Wiesel. Numerous survivors from Hungary also became United States Holocaust Memorial Museum survivor volunteers.

The First Stage of the Holocaust in Hungary, 1938–March 1944

The first stage of the Holocaust in Hungary began around 1938 and ended in March 1944. During this time, the Hungarian government persecuted Jews on its own initiative. Its anti-Jewish policies built on a longer history of antisemitism in Hungary.

Beginning in 1920, the Hungarian government was a right-wing and authoritarian regime. It was led by Miklós Horthy. Horthy and other Hungarian leaders were nationalist, antisemitic, and anticommunist.

Until March 1944, Hungary was a sovereign state that had friendly diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany. The two governments shared a similar worldview. In November 1940, Hungary joined the Axis alliance, becoming a formal ally of Nazi Germany.

Hungarian Antisemitic Legislation

During the Horthy regime (1920–1944), the Hungarian government passed anti-Jewish laws. The goal was to exclude Jews from the country’s social, economic, political, and cultural life. According to the 1920 census, there were about 470,000 Jews living in Hungary at the time. The Jewish population made up almost 6 percent of Hungary’s total population of nearly 8 million.

The earliest of Hungary’s anti-Jewish laws was enacted in 1920, before the Holocaust began. That year, the Hungarian parliament passed the numerus clausus law. This law limited university enrollment for Jewish students. It was the first anti-Jewish law enacted in Europe after World War I (1914–1918).

Hungary’s anti-Jewish persecution and legal discrimination began to escalate in 1938. Between 1938 and 1941, the Hungarian government enacted three main anti-Jewish laws:

- The First Jewish Law (May 1938) established quotas restricting the number of Jews in certain sectors of the country’s economy to 20 percent. These sectors included white-collar professions and business/industry.

- The Second Jewish Law (May 1939) defined Jews in racial terms and restricted voting rights for certain Jews. It also tightened the quotas set in the previous year.

- The Third Jewish Law (August 1941) banned marriages and sexual relationships between Jews and non-Jews.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Hungarian government passed numerous other anti-Jewish laws. Most of them excluded Jewish people from various aspects of economic and social life. As a result, tens of thousands of Jews lost their jobs, businesses, or livelihoods.

Hungarian Territorial Expansion, 1938–1941

In 1938, Hungary began to expand its territory beyond the borders agreed upon after World War I. It did so with German support and in conjunction with Nazi Germany’s territorial expansion. This effort helped Hungary’s leaders achieve their geopolitical goal to reclaim territories the country had lost in the post-World War I peace treaties.

Between 1938 and 1941, Hungary acquired territories (listed in Table 1) from the neighboring countries of Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. These territories were home to multiethnic, multi-religious populations. Ethnic Hungarians, Romanians, Slovaks, Serbs, Jews, and many others lived in these areas. In all of the annexed territories, the Hungarian government carried out persecutions, expulsions, and violence against non-Hungarian populations.

Jews living in the annexed territories faced Hungary’s anti-Jewish laws and policies. The Hungarian census of 1941 counted 725,007 people who identified themselves as Jews. About 325,000 of them lived in Hungary’s annexed territories. In 1941, the Jewish population made up about 5 percent of the total population of Greater Hungary (14,683,323). In addition, about 100,000 more people were considered racially Jewish under the Second Jewish Law (1939). This was the case even though they did not identify themselves as Jewish.

Table 1. Hungarian Territorial Expansion and Jewish Population Numbers, 1938–1941

| Territory | Annexed from | Date | Total Population of Annexed Territory (1941) | Jewish Population (1941) |

| Southern Slovakia and a small part of southern Subcarpathian Rus (First Vienna Award) | Czechoslovakia | November 1938 | 1,000,000 | 68,000 |

| Subcarpathian Rus | Czechoslovakia | March 1939 | 700,000 | 78,000 |

| Northern Transylvania (Second Vienna Award) | Romania | August–September 1940 | 2,600,000 | 146,000 |

| Bačka, parts of Baranja, Međimurje, and Prekmurje | Yugoslavia | April 1941 | 1,000,000 | 14,000 |

Exploitation of Jewish Men in the Hungarian Forced-Labor Service System, 1939–1945

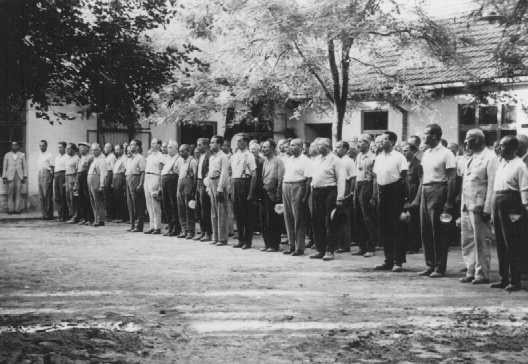

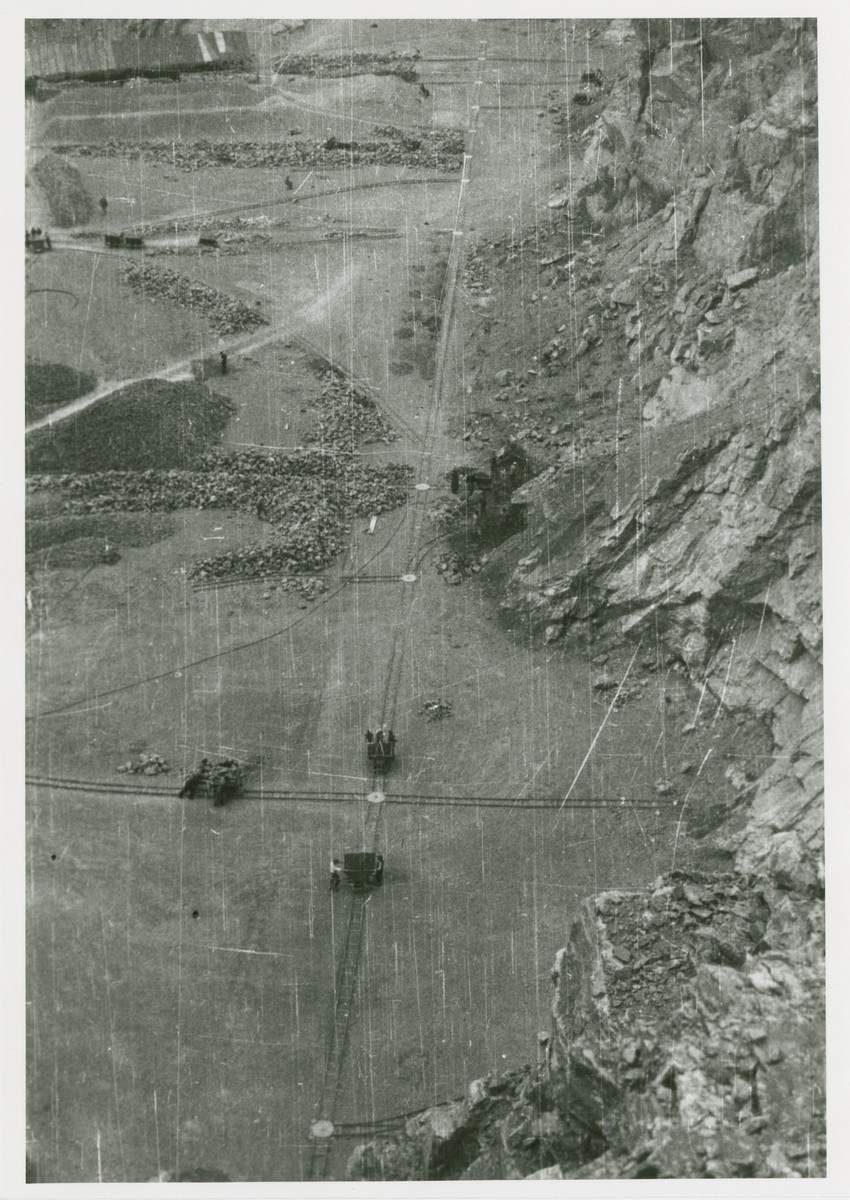

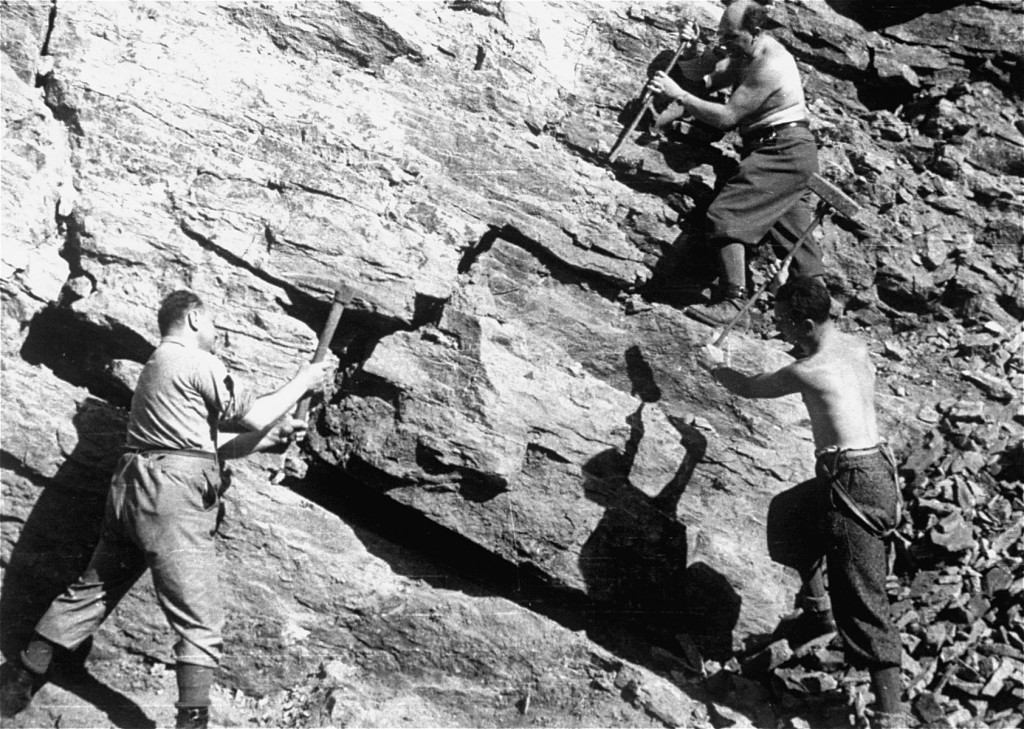

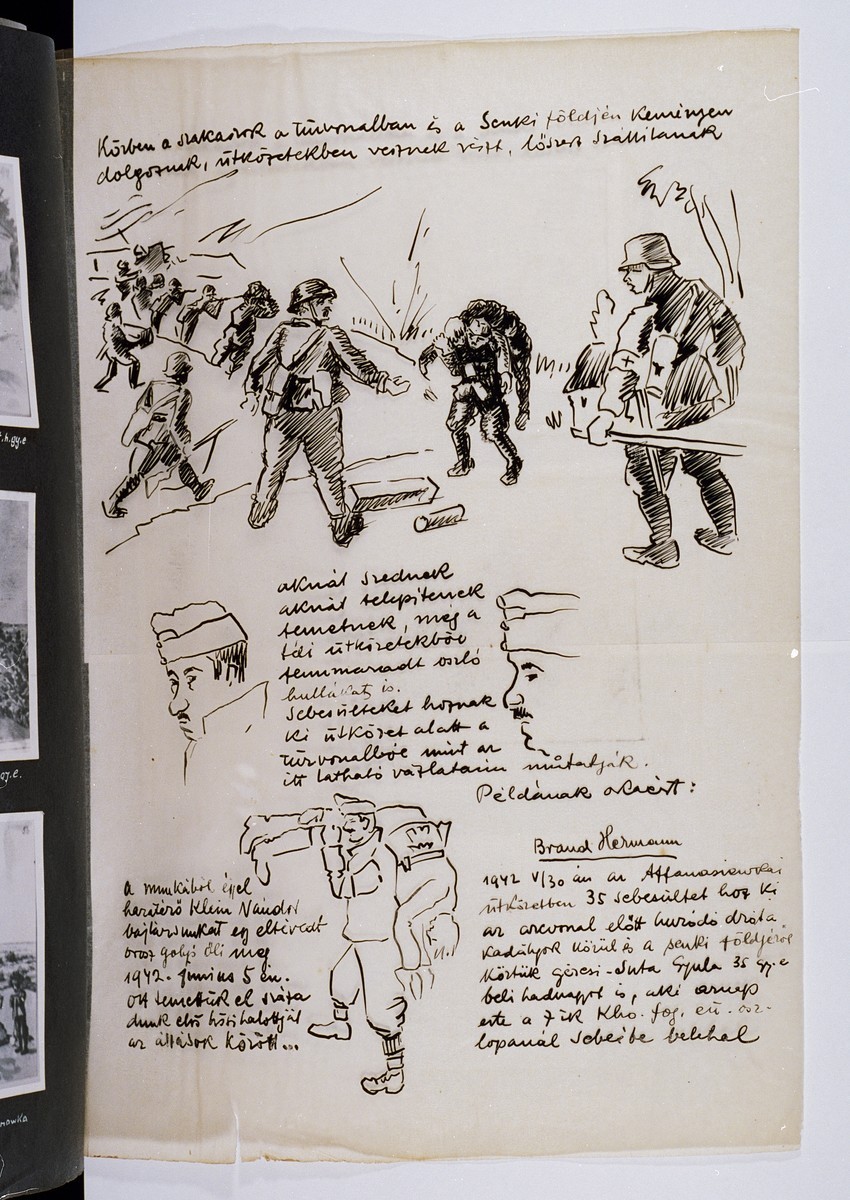

From 1939 to 1945, the Hungarian government exploited Jewish men of military age in the labor service system (munkaszolgálat).

The Hungarian government created the labor service system as a substitute for regular military service. It was intended for those men deemed unreliable by the government. Political opponents, members of certain Christian sects, Romanians, Serbs, and especially Jews were among those forced into the labor service system. At first, labor service was performed within Hungary and its annexed territories. Conditions were relatively good.

After Hungary entered World War II in spring 1941, the Hungarian Defense Ministry transformed the labor service system into a more repressive and overtly antisemitic institution. Jewish labor servicemen were separated from their non-Jewish counterparts. They were no longer given uniforms. Further, they were required to wear discriminatory armbands marking them as Jews.

Beginning in summer 1941, tens of thousands of Jewish labor servicemen were deployed near the front lines in Axis-occupied eastern Europe, especially in Ukraine. The Hungarian officers often treated these men poorly and subjected them to murderous violence. The Jewish men did not have adequate shelter, food, clothing, or medical care. A significant number of them ended up in Soviet captivity as prisoners of war.

Scholars estimate that approximately 100,000 Jewish men were forced to participate in the labor service. Between 25,000 and 42,000 of them died before Germany occupied Hungary in March 1944.

Deportation of Jews from Hungary and the Massacre at Kamenets-Podolsk, 1941

One of the most notorious acts of antisemitic violence in the first stage of the Holocaust in Hungary took place in the summer of 1941. It occurred in the wake of the Axis attack on the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa). In July–August 1941, Hungarian officials rounded up and deported Jewish people whom they deemed “unsuitable aliens and foreign citizens.” The Hungarian government deported more than 20,000 Jews across the border into Axis-occupied Galicia (then Poland, today Ukraine). The deportations were speedy, haphazard, chaotic, and inhumane.

Eventually, most of the Jews deported from Hungary (about 14,000–16,000) were taken to the town of Kamenets-Podolsk. There, they were imprisoned in a ghetto. On August 26–28, Nazi German SS and police units and their local Ukrainian collaborators carried out a mass shooting operation at Kamenets-Podolsk. They murdered 23,600 Jews. It is likely that some Hungarian military officials saw, and perhaps took part in, the roundup and mass shooting operation.

Many of those Jews deported from Hungary who were not killed at Kamenets-Podolsk were shot in subsequent massacres, died in ghettos, or were murdered in the Belzec killing center. Perhaps as many as 2,000 Jewish refugees managed to return to Hungary. Their reports of what had happened in Galicia were often met with disbelief.

The Bačka Raids in Hungarian-Occupied Yugoslavia

In January 1942, Hungarian military units carried out raids in the Hungarian-annexed Bačka region of Yugoslavia. These raids were supposedly in response to partisan activity. Violence took place in the city of Novi Sad (Újvidék in Hungarian) and other cities in the region. Hungarian authorities targeted Serbs, Jews, and others. About 1,000 Jews and 2,500 Serbs were killed. The perpetrators of the massacres were tried by Hungarian courts in 1943–1944.

Hungarian Refusals to Comply with German Deportation Requests, 1942–1944

In the first stage of the Holocaust in Hungary, the Hungarian government did not fully participate in the Nazi-led mass murder of Jews.

Nazi Germany’s deadly treatment of Jews had escalated quickly after its invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. German units began to murder entire Jewish communities in mass shooting operations. Then, in late 1941 and 1942, the Nazi German regime built killing centers designed to murder Jews using poison gas. Nazi German authorities deported Jews from all over Europe to these killing centers. They relied upon their allies and collaborators to assist them.

In 1942, the Nazi German government began to pressure the Hungarian government to deport all Jews from Hungary to German-controlled territory. However, Horthy and Prime Minister Miklós Kállay (in office March 1942–March 1944) refused. Horthy and Kállay responded that the fate of Hungary’s Jewish population was a domestic issue. They argued that deporting Jews could have potentially devastating consequences for Hungary’s economy.

This refusal to cooperate meant that hundreds of thousands of Jews remained alive in Hungary during the peak years of mass killing. Still, in this period, Jews in Hungary faced significant hardships because of the country’s antisemitic laws and the forced labor service system. But, unlike Jews under direct Nazi occupation elsewhere, most Jews in Hungary remained in their own homes with access to enough food and other resources. Hungary even attracted thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi mass murder in neighboring countries.

Hungary’s time as a relative safe-haven from Nazi mass murder came to an abrupt end in March 1944, when Nazi Germany occupied the country.

The Second Stage of the Holocaust in Hungary, March 1944–1945

In March 1944, Nazi Germany decided to occupy their ally Hungary for military reasons related to Hungary’s role in the ongoing war effort. On March 19, 1944, the German military entered Hungary relatively unopposed. The Hungarians quickly complied with German demands. As a result, most German troops remained in Hungary for only a short period of time. The Germans, however, continued to play a dominant role in Hungarian politics.

The German occupation authorities permitted Horthy to remain in his position as regent of Hungary. Many other Hungarian officials also kept their positions. But, the Germans insisted that Horthy replace Prime Minister Kállay with the pro-German Döme Sztójay. As prime minister, Sztójay cooperated with the German authorities. Several radical right-wing antisemites received important positions in his government.

One of Nazi Germany’s goals after occupying Hungary was to carry out the deportation and mass murder of Jews from the country. In March 1944, there were between 760,000 and 780,000 Jews living in Hungary. This was the largest Jewish population still alive in Europe.

The German occupation of Hungary was an important turning point. Within the next year, Germans and their Hungarian collaborators would murder about 500,000 Jews from Hungary.

New Antisemitic Measures in German-Occupied Hungary, Spring 1944

After the German occupation, the Hungarian government enacted dozens of antisemitic decrees. Its goal was to completely isolate, stigmatize, and impoverish Jews in Hungary. New antisemitic regulations forced Jews to hand over property such as cars, telephones, radios, and bicycles. Other decrees banned them from attending movies or plays with non-Jews. Additional decrees decreased Jews’ food rations.

In late March 1944, the Hungarian government announced that beginning on April 5, all Jews aged 6 and older would be required to wear a yellow Star of David badge on their clothing.

Across the country, Hungarian authorities—including mayors, police officers, and gendarmerie officials—cooperated in carrying out these measures. Following orders from the government, they instructed Jewish communities to create registration lists of all Jews in their jurisdiction.

Hungarian Transit Ghettos and the Deportation of Jews from Hungary, April–July 1944

German and Hungarian authorities quickly began to plan for the ghettoization and deportation of Jews from Hungary. Nazi SS officer Adolf Eichmann and his team of deportation experts came to Budapest to facilitate this process. In the spring and summer of 1944, Hungarian and German authorities divided Hungary into six operational zones. In each zone, the creation of ghettos preceded deportation.

Beginning in April 1944, Hungarian authorities set up transit ghettos in towns and cities. The Hungarian authorities included regional and district government officials, mayors, public health officials, policemen, and gendarmes. The ghettos were often established in Jewish neighborhoods or in large buildings like factories, warehouses, or brickyards. They were usually located near railroad facilities to simplify deportation. Jews from smaller towns and villages were concentrated in ghettos in larger cities. They were imprisoned in these transit ghettos for days or weeks. They were guarded by Hungarian authorities and provided with limited food, shelter, and medical care. A small number of German authorities participated in this process. Widespread plunder, theft, and torture accompanied the process of ghettoization.

Systematic deportations of Jews from the transit ghettos began in mid-May 1944. Zone by zone, German deportation experts and Hungarian gendarmes forced Jews from the transit ghettos onto freight cars. Between May 15 and July 9, 1944, approximately 437,000 Jews were deported from Hungary on 147 trains. About 420,000 of them were sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center. When they arrived there, they underwent the selection process. About 100,000 Jews from Hungary were selected for forced labor at Auschwitz. The remainder—approximately 330,000 Jews (about 75 percent)—were murdered in the gas chambers upon arrival. The victims included men, women, and children. This was the deadliest period at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Horthy Halts the Deportations, June–July 1944

On July 7, 1944, Horthy ordered a halt to the deportations of Jews from Hungary. He did so because of Germany’s worsening military position, international threats, and pressure from his inner circle. Nevertheless, deportations to Auschwitz from cities around Budapest continued for two more days. They were halted on July 9. Despite Horthy’s orders, Eichmann, his German deportation experts, and their allies in the Hungarian government tried to keep going. They carried out a small number of deportations of Jews to Auschwitz from Hungarian internment camps in late July and August 1944.

The only Jewish community that remained mostly untouched by the deportations of the previous months was Budapest.

“Yellow Star Houses”: Budapest, Summer 1944

In July 1944, the large Jewish community of Budapest numbered some 200,000 people.

That summer, conditions in Budapest were grim. The full force of the Hungarian government’s antisemitic laws and measures was still in effect. News of deportations from the countryside made its way to the capital. The Hungarian government also introduced a form of dispersed ghettoization in the city. The Hungarian government and members of the Budapest municipal government forced Jews to live in designated “yellow star houses.” The authorities also imposed a curfew and other restrictions.

Rescue Operations in Hungary

The timing of the Holocaust in Hungary allowed for several extraordinary rescue operations. Both Jews and non-Jews led these efforts.

Notably, Jewish leaders of the Relief and Rescue Committee of Budapest tried to negotiate with and bribe Nazi leaders to save Jews in Hungary. The committee negotiated a rescue operation known as the Kasztner Transport. In exchange for money and valuables, Nazi officials agreed to allow a transport of Jews to go to safety. More than 1,600 Jews survived in this way.

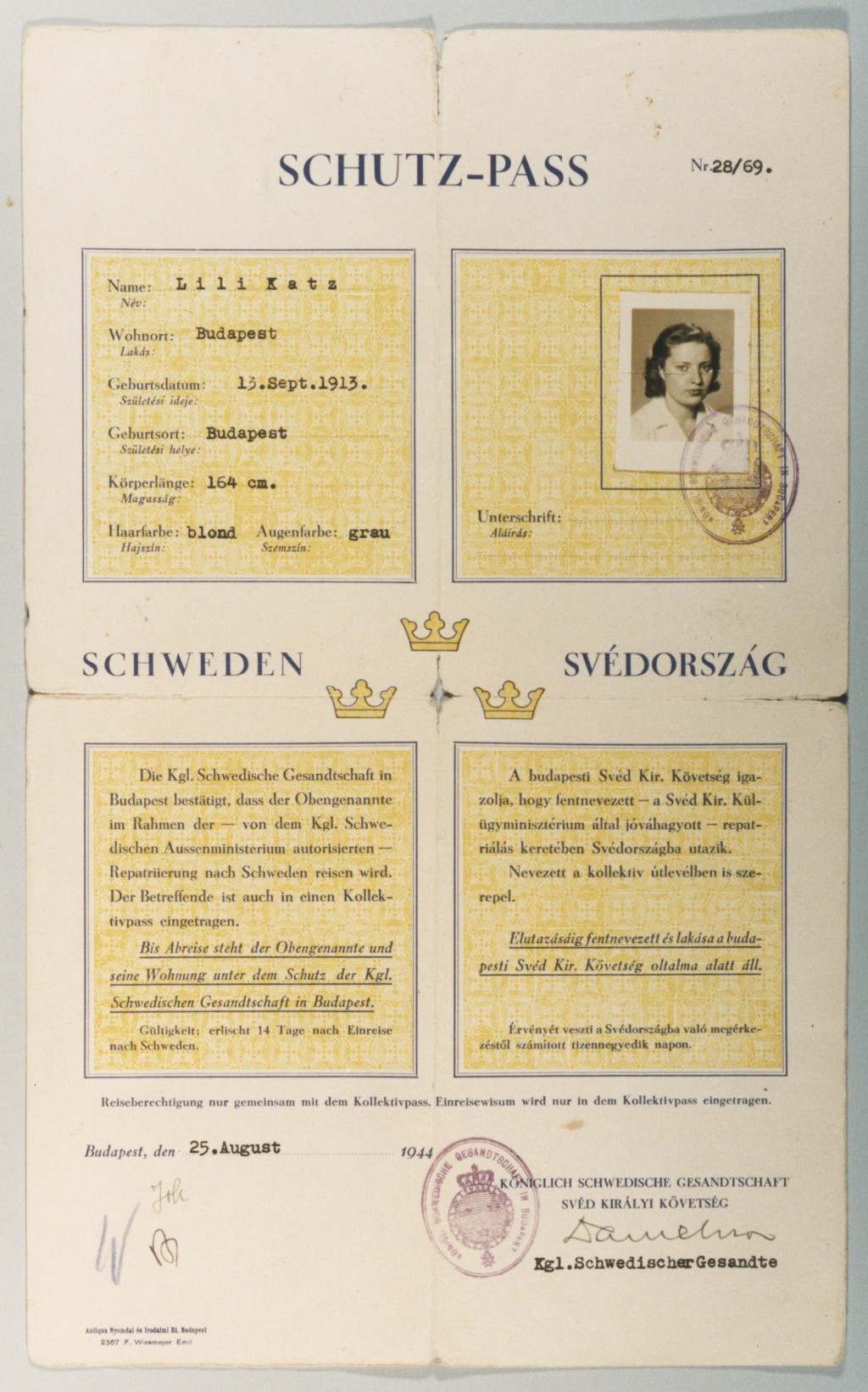

In the summer and fall of 1944, a number of international rescue operations were underway in Budapest. They were led by members of diplomatic missions from neutral countries, especially those from Sweden and Switzerland. Raoul Wallenberg (Sweden) and Carl Lutz (Switzerland) coordinated the creation and distribution of protective passes. A protective pass (sometimes called a Schutzpass) was a piece of paper that indicated a person (or family) was supposedly under the protection of the neutral power. The rescuers also created safe houses for Jews in the city. They often worked closely with Jewish organizations and rescue groups. Wallenberg was recruited by the American War Refugee Board.

Arrow Cross Takeover of Hungary

In August 1944, as the tide of the war shifted further in favor of the Allies, Horthy dismissed Prime Minister Sztójay. Horthy installed a new government. He also dismissed many of the most extreme right-wing antisemitic members of the Sztójay government. In September, the Red Army (the Soviet military) crossed the border into Hungary. Horthy sent representatives to negotiate a ceasefire with the Soviets.

On October 15, 1944, Horthy attempted to openly break with Nazi Germany. He announced a ceasefire with the Soviets. However, Horthy had planned poorly. The Germans and their Hungarian collaborators quickly took control of the situation. German authorities detained Horthy. They threatened his son’s life and demanded that he install a new government. Horthy agreed. The new government was led by Ferenc Szálasi. Szálasi was the leader of the fascist and radically antisemitic Arrow Cross Party (Nyilaskeresztes Párt). Under Arrow Cross leadership, Hungary continued to fight against the Soviets alongside Nazi Germany.

Arrow Cross militias conducted a reign of terror against the Jews of Budapest. Arrow Cross members (called “Nyilas”) shot Jewish people into the Danube River.

Deportations from Budapest, Fall 1944

On October 20, Arrow Cross militias began rounding up Jews for forced labor. A day later, the Arrow Cross government issued an order that Jewish men and women would be required to perform forced labor. Tens of thousands of Jews were rounded up. Initially, they had to dig anti-tank ditches around the city. On November 6, the government began deporting them on foot about 100 miles west to Hegyeshalom (a village along the Austria-Hungary border). Many Jews died or were shot along the way. Jews who survived the trip were handed over to the Germans, supposedly on loan. The Hungarians also “loaned” Jewish labor service battalions. Diplomats (including Raoul Wallenberg and Carl Lutz), Jewish organizations, and ordinary Hungarians intervened as much as possible. They tried to provide aid or save people from deportations.

Tens of thousands of Jewish people from Hungary were handed over to the Germans in November–December 1944. The Germans required them to perform forced labor. Many forced laborers had to build defensive trenches. They worked under deadly and grueling conditions. Thousands died or were killed. Many others later died on death marches in spring 1945.

The Budapest Ghetto and the International Ghetto, November–December 1944

In late 1944, the Arrow Cross regime created two ghettos in Budapest.

One was a fenced-in ghetto in the traditional Jewish quarter of Budapest. The regime ordered Jews living in the “yellow star houses” to move into this ghetto. The Budapest ghetto was also called the “Pest ghetto” or the “large ghetto.” It was extremely overcrowded. The ghetto was sealed in December 1944. It held about 70,000 people. Approximately 3,000 Jewish people died there.

Jews with international protective passes were housed in what became known as the “international ghetto.” This ghetto was also called the “protected ghetto” or the “small ghetto.” The area was not fenced in, but included a cluster of apartment buildings under international protection. Officially, 15,600 people lived in the international ghetto. In reality, thousands more sought safety there. This included people with forged protective papers or those without any actual papers.

Thousands of Jews in Budapest went into hiding rather than move into either ghetto.

The End: The Liberation of Jews in Hungary, 1944–1945

As the Red Army (the Soviet military) advanced westwards, they liberated Jews from Hungary. Among those liberated were Jews serving in labor service battalions and Jews in hiding.

On November 2, 1944, the Soviets began their attack on Budapest. In the winter of 1944–1945, the Soviets encircled Budapest and laid siege to the city. German and Hungarian forces fought fiercely to defend the capital. During this time, Arrow Cross militias continued to perpetrate violence against Jews. The Soviets liberated the international ghetto on January 16, 1945, and the Budapest ghetto on January 17–18. They conquered the rest of the city in February. By April 1945, the Soviets had completely taken over Hungary.

The Soviets liberated approximately 119,000 Jews in Budapest. They freed a small number in the rest of the country.

Number of Victims of the Holocaust in Hungary

In 1941, approximately 825,000 Jews were living in Hungary and its annexed territories. More than 65 percent of them (about 550,000 people) were murdered in the Holocaust.

Between 44,000 and 63,000 Jewish people died or were killed in the first stage of the Holocaust in Hungary.

About 500,000 Jews from Hungary were killed in the second stage. Of these, approximately 330,000 were murdered in the gas chambers upon arrival at the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center. Tens of thousands more died while imprisoned in Auschwitz or other German concentration camps and forced labor camps, as well as on death marches. Thousands were murdered in Budapest by Hungarian Arrow Cross militiamen.

Approximately 250,000 Jews from Hungary survived the Holocaust. Their survival was only possible because of a confluence of factors, most notably timing, rescue, and luck.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

In the late 19th century, Hungary was an autonomous part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During World War I (1914–1918), Austria-Hungary fought on the side of the Central Powers, which included the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire. As it became clear that the Central Powers were losing the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed. New independent nation-states were founded in its place. Among them was Hungary. The collapse of the empire led to significant diplomatic and military conflicts about what territory should belong to whom. In the postwar peace negotiations, territory that had been part of Hungary was allocated to other countries. These countries included Romania, the newly established state of Czechoslovakia, and the kingdom that became known as Yugoslavia. Hungary’s territorial losses were confirmed in the Treaty of Trianon. This treaty was signed in Paris in June 1920. Postwar Hungary included just one-third of Hungary’s prewar territory.

-

Footnote reference2.

The first deportations of Jews from Hungary to Auschwitz were from Hungarian internment camps in late April 1944. These deportations preceded the systematic deportations that began in mid-May.

-

Footnote reference3.

In total, scholars estimate that about 430,000 Jews from Hungary were deported to Auschwitz in 1944. The bulk of the deportations to Auschwitz took place between May 15 and July 9. In that time period, about 420,000 Jews were deported from Hungary to Auschwitz. The total number of 430,000 includes transports sent from Hungary to Auschwitz in late April 1944, and several transports from later in the summer and early fall of 1944. In June 1944, several transports carrying about 15,000 Jews were deported from transit ghettos in Hungary to Strasshof, a transit camp near Vienna. From there, they were assigned to forced labor in Vienna. Scholars estimate that 75 percent of Strasshof deportees survived.

Critical Thinking Questions

What pressures and motivations influenced Hungarian officials and citizens to persecute Jews before the Nazis took over in March of 1944?

Did the Hungarian government's choices, laws, and actions mirror those of Nazi Germany? How?

How did anti-Jewish persecution increase after the Nazi takeover?

How did the change in Hungary’s leadership in October 1944 increase the persecution and murder of the Jews?