The Nazi Persecution of Black People in Germany

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, there were several thousand Black people living in Germany. The Nazi regime harassed and persecuted them because the Nazis viewed Black people as racially inferior. While there was no centralized, systematic program targeting Black people for murder, many Black people were imprisoned, forcibly sterilized, and murdered by the Nazis.

Key Facts

-

1

The Nazis harassed and discriminated against Black people in Germany. The regime’s racial laws limited their social and economic opportunities.

-

2

The Nazi regime forcibly sterilized an unknown number of Black and multiracial people, including at least 385 multiracial Rhineland children (derogatorily called the “Rhineland Bastards”).

-

3

There was no coordinated arrest wave targeting all Black people in Germany. Nonetheless, many Black people ended up imprisoned in workhouses, prisons, hospitals, psychiatric facilities, and concentration camps.

Introduction

When Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power in 1933, there were several thousand Black people living in Germany. The Nazi regime discriminated against them because the Nazis viewed Black people as racially inferior. During the Nazi era (1933–1945), the Nazis used racial laws and policies to restrict the economic and social opportunities of Black people in Germany. They also harassed, imprisoned, sterilized, and murdered an unknown number of Black people.

The Origins of Germany’s Black Community before World War I

Before World War I, several thousand Black people came to Germany from Africa, North and South America, and the Caribbean. Almost all of these sojourners were men. A significant number of them came from Germany’s African colonies, especially from Cameroon. During the colonial period, the Germans imposed strict migration restrictions for their colonial subjects. The German authorities wanted to limit the number of Black permanent residents in Germany and curtail the growth of any significant Black population there.

Despite these restrictions, Black men from the colonies and beyond often came to Germany to learn trades or engage in other work. They sought educational opportunities as apprentices and students. They also came to work as servants and sailors. A significant number came to Germany as paid performers in exploitative public exhibitions called human zoos.

The majority of Black visitors intended on staying in Germany for only a short time. Most Black men and women who traveled to Germany returned home before World War I (1914–1918). A smaller number chose to remain. Additionally, some Black people who had not planned on staying in Germany were trapped there by the war. The outbreak of hostilities in 1914 limited international travel and migration within and beyond Europe.

Even after World War I ended in 1918, most of Germany’s former colonial subjects could not easily return to their places of birth or move abroad. This was because Germany lost its colonies in the postwar peace settlements. In the new postwar order, Germany’s former colonial subjects had neither German citizenship nor access to passports or travel documents. They were stranded in Germany (then known as the Weimar Republic), which no longer had any formal connection to its former colonies.

Black Residents in Germany during the Weimar Period (1918–1933)

During the Weimar Republic, Germany was home to a small, male-dominated Black community whose members had mostly migrated to Germany before World War I. By the early 1920s, some of these men met and married local German women and had families. Many Black-German families lived in close proximity to one another in large cities, such as Berlin and Hamburg, as well as in Munich, Hanover, and Wiesbaden.

Marginalization in Weimar German Society

Racism was a part of Black people’s everyday lives in Weimar Germany. This made it difficult for them to find employment, a situation exacerbated by the Great Depression. White German women who married Black men were often ostracized, making it difficult for them to find work as well. Black people were sometimes even marginalized within their own extended families. For example, Theodor Wonja Michael, born in 1925 in Berlin to a Black Cameroonian father and a white German mother, remembered that his father was a “taboo subject” in his mother’s family.

A lack of citizenship was a central problem for Black-German families. As a result of the complexities of German citizenship at the time, the overwhelming majority of Black men were not German citizens. This impacted their wives and children whose own citizenship depended on that of the husband and father. Without citizenship, Black men, their white wives, and their children could not fully integrate into economic, social, and political life in Germany.

Black Performers and Weimar Culture

While the Black community in Germany was small and marginalized, it was not an unknown presence. In the 1920s, Black people in Germany were particularly visible as part of the Weimar era’s vibrant and innovative cultural life. Germans’ growing fascination with African American music and performance presented Black people in Germany with new opportunities to appear on stage, whether they were actually African American or not. They performed in theaters, circuses, films, and at live music venues like nightclubs and cabarets.

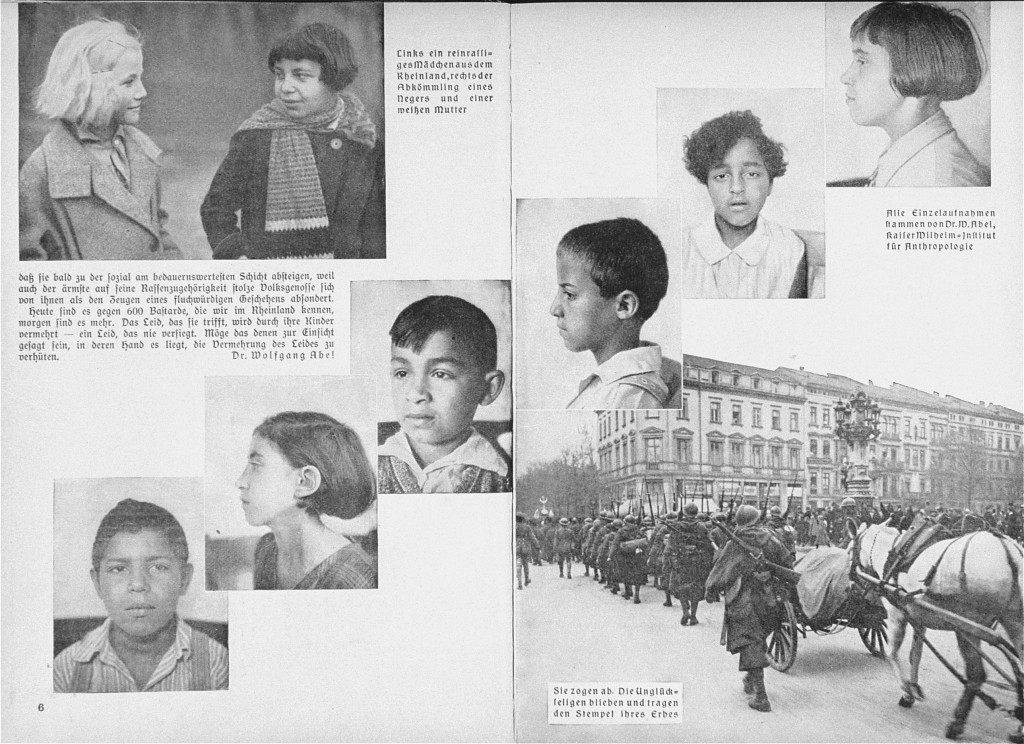

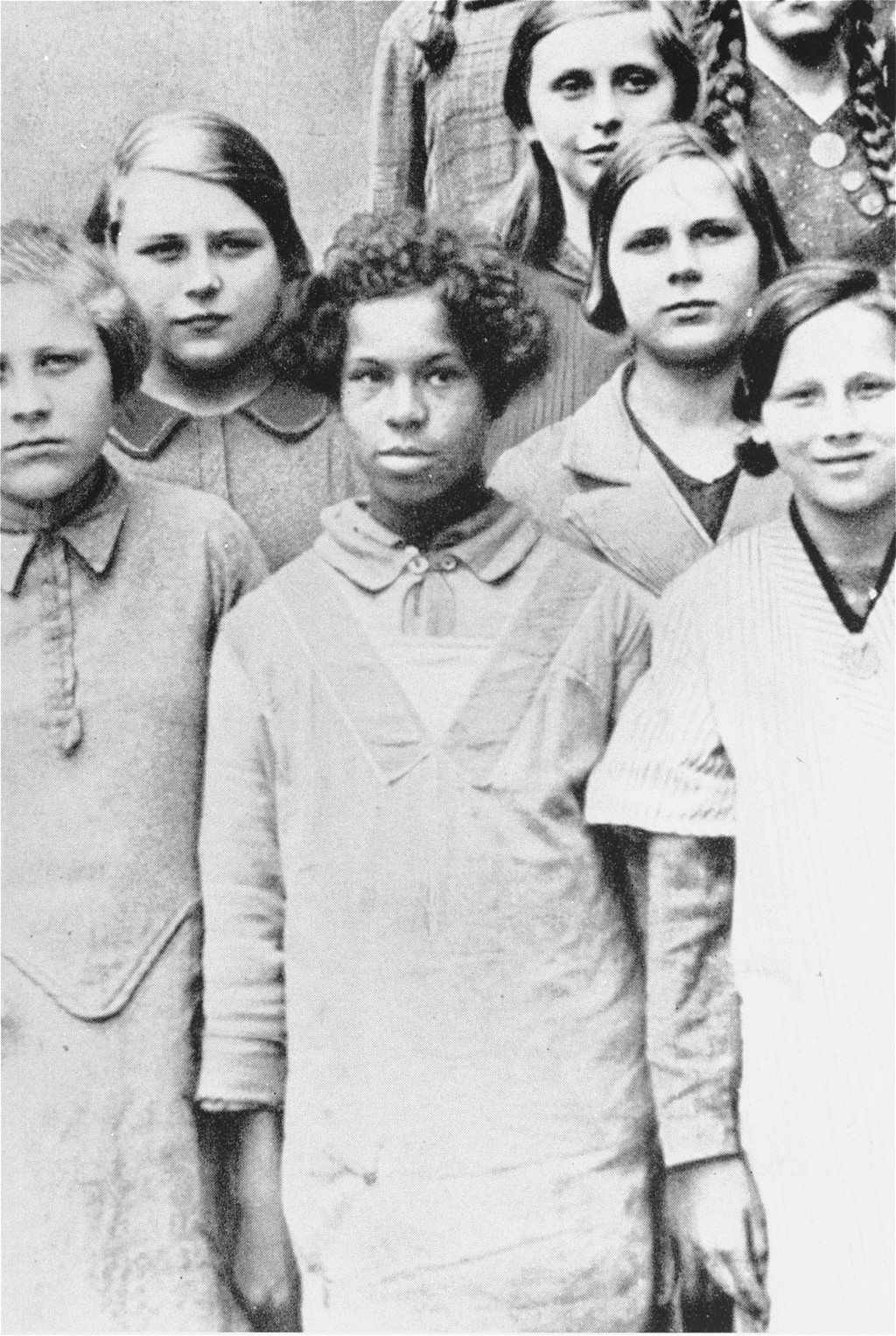

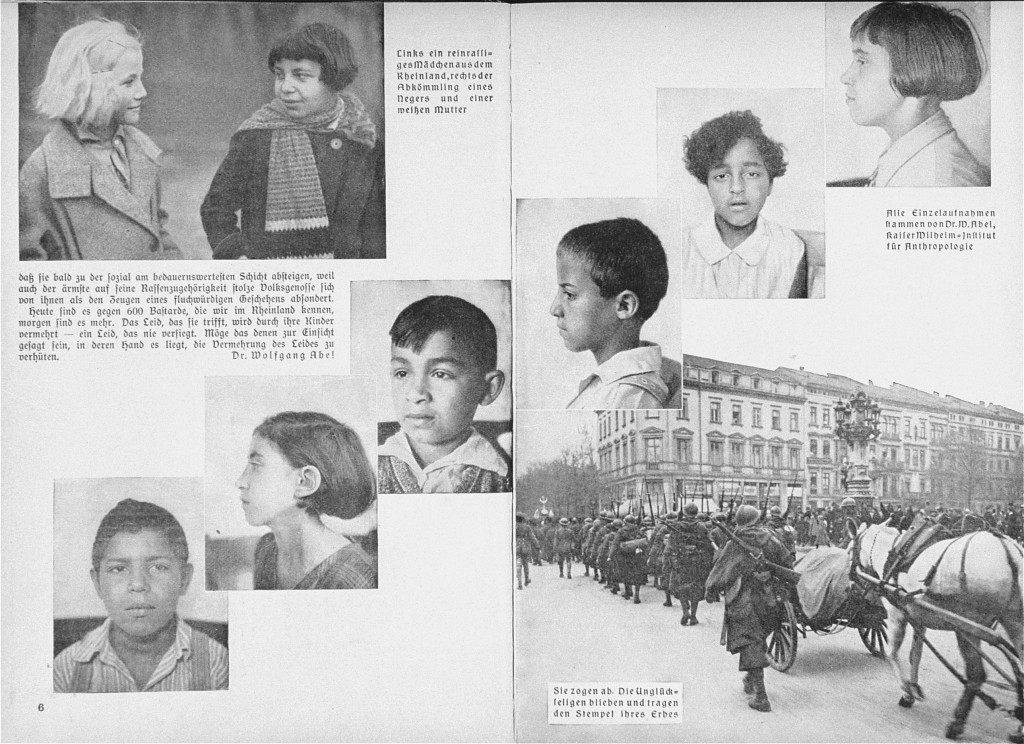

“Rhineland Bastards”: Multiracial Children in the Rhineland

During the Weimar era, there were also between 600-800 multiracial children born in the Rhineland, a region in western Germany. The German press referred to them using the derogatory label “Rhineland Bastards” (“Rheinlandbastarde”). Their mothers were white German women and their fathers were mostly French colonial soldiers who had been part of the large Allied military occupation of the Rhineland (1918–1930). While many of these soldiers were North African or Asian, in public discourse they were all racialized as Black.

These children had an ambivalent place in Weimar German society, resulting from their interracial parentage. They were often discriminated against because of their fathers and their physical appearance. However, they were not total outsiders. Most had German citizenship from their unmarried mothers. Socially, these children were often ostracized. They experienced racism from their neighbors, classmates, and even in their own families. Some remained with their birth mothers or their families, but others were placed in children’s homes or adopted.

Black People under the Nazi Regime (1933–1945)

Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party began to put their discriminatory and false ideas about race into law and practice when they came to power in Germany in 1933. The Nazis wanted to create a racially pure Germany and they considered Germans to be members of the supposedly superior “Aryan” race. They targeted Jews, Roma, and Black people as “non-Aryans” and as members of supposedly inferior races. The Nazis passed laws that limited the rights of non-Aryan Germans. These laws were primarily intended to exclude Jews, but they also applied to Black and Romani peoples.

For Black Germans, the Nazi era was a time of escalating persecution, marginalization, and isolation. Though they had faced racism during the Weimar era, the institutionalized racism of the Nazi regime made life for Black people and their families even more difficult and precarious. As a result, Black people in Germany saw the Nazi rise to power as a turning point in their lives.

The Nazis persecuted Black people in Germany not only for their race, but also for other reasons, such as their politics. For instance, Hilarius “Lari” Gilges (b. 1909) was a Black German dancer and Communist activist from Düsseldorf, Germany. Nazis murdered him on June 20, 1933, and left his body in the street. Gilges’ murder took place during the first months of the Nazi regime, as the Nazis sought to destroy the German Communist movement.

Nazi racist ideology permeated all aspects of life in Germany. Many Germans embraced this ideology and openly discriminated against Black people on their own initiative. As a result, it became increasingly difficult for Black people to find and keep work. Colleagues and bosses were reluctant to work with people whose skin color marked them as outsiders in the Nazi racial community. Firings, evictions, and poverty were common. Some Black people remember life in Nazi Germany as a time in which strangers spat on them and called them racial slurs with impunity.

The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service

It was clear almost immediately that the Nazi regime intended to formally exclude Black people from German society.

In April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service removed people of “non-Aryan descent” from the German civil service. The decree was vague as to how exactly to define “non-Aryan descent.” The intention to exclude Jews was obvious, but subsequent decrees clarified that this also applied to Black and Romani people. In practice, relatively few Black people were directly affected by this law, because only citizens could be civil servants. And most of those Black people who were German citizens were still too young to be employed in the civil service. However, this decree and subsequent race-based restrictions severely limited future job opportunities and career paths. It also made clear that the Nazis did not consider Black people part of the German national community (Volksgemeinschaft).

The Nuremberg Race Laws

In September 1935, the Nazi regime announced the Nuremberg Race Laws, which put Nazi ideas about race into law. These laws primarily targeted Jews. But, beginning in November 1935, the Nuremberg Laws also applied to Romani and Black people, whom the regime referred to derogatorily as “Gypsies, Negroes and their bastards” (“Zigeuner, Neger und ihre Bastarde”).

There were two Nuremberg Race Laws. The first, the Reich Citizenship Law, defined a German citizen as a person who is “of German or related blood.” The point was to exclude people whom the regime saw as racially inferior (namely Jews, Roma, and Black people) from having political rights in Germany.

The second was the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor. This law banned race-mixing or what was called “race defilement” (Rassenschande). It forbade future intermarriages and sexual relations between Jews and people “of German or related blood.” A subsequent supplement to the law forbade Black people in Germany to marry “people of German or related blood.” The goal was to prevent Black people from marrying and having children with Germans.

Persecution and Discrimination against Interracial Couples in Nazi Germany

The Nuremberg Race Laws made it very difficult for Black people in Germany to marry, start families, or build a future. They particularly affected those of reproductive and marrying age. While it was legal for Black people to marry each other, these couples were rare because of the small size of the Black community.

Despite the Nuremberg Laws, some Black people and German “Aryans” still became romantically involved with one another. These relationships were dangerous for both partners, especially if they chose to try to legally marry. In Nazi Germany, everyone was required to apply for permission to marry. When interracial couples applied, their applications were consistently denied for racial reasons. These applications brought their interracial relationships to the attention of government authorities. This often had dire consequences for the couple. In multiple cases, marriage applications resulted in harassment, sterilization, and the breaking up of partnerships.

Legal couples whose marriages pre-dated the Nuremberg Laws were harassed by the Nazi regime. The regime pressured white German women to divorce their Black husbands. Interracial couples and their children were often humiliated and even assaulted when they appeared together in public. For instance, Nazi journalists in Frankfurt persistently mocked and degraded Dualla Misipo, a Cameroonian man, and his Black-German family, on the pages of the local party newspaper. Neither he nor his white German wife could earn a living.

There were at least two known instances in which Black men were punished at least in part because they were having sexual relationships with white German women.

Excluding Black Children from Schools

Like their parents, many Black children in Germany experienced the Nazi era as a time of increased loneliness, isolation, and exclusion. Some Black children felt German and wanted to be a part of the excitement. But, Nazi racial ideology had no place for Black-German children. Hans Massaquoi, whose father was Liberian and whose mother was German, remembered when his class went to a parade, where Adolf Hitler would appear.

“Now we would get a chance to see [Hitler] with our own eyes…There I was, a kinky-haired, brown-skinned eight-year-old boy amid a sea of blond and blue-eyed kids, filled with childlike patriotism, still shielded by blissful ignorance. Like everyone around me, I cheered the man whose every waking hour was dedicated to the destruction of ‘inferior non-Aryan people’ like myself.”

Hans J. Massaquoi, Destined to Witness: Growing up Black in Nazi Germany

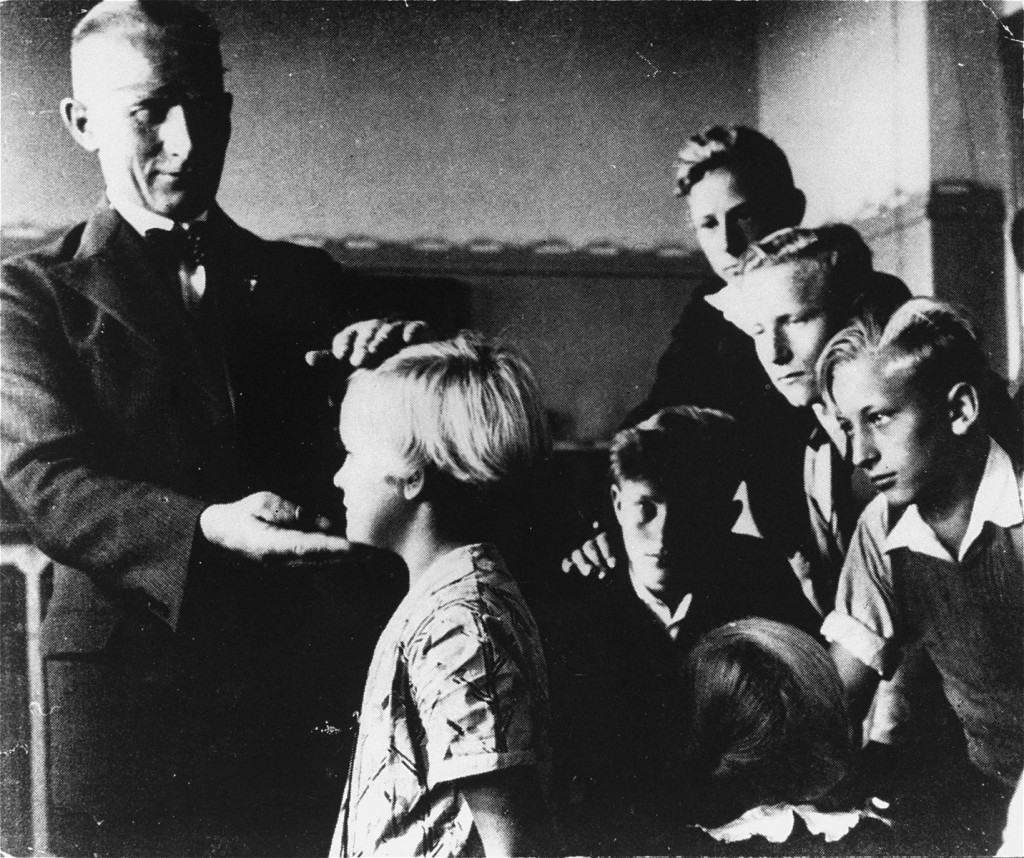

For Black children in Nazi Germany, schools became sites of humiliation. Black children were often degraded in racial science classes and ridiculed by teachers who supported the Nazis.

Just as the Nazification of the education system greatly restricted the rights of Jewish children to attend public schools, it also impacted Black children over the course of the 1930s. Some Black students were expelled and unable to complete their education. Few private schools would accept Black students. Finding apprenticeships, which in Germany was crucial to finding employment, became increasingly difficult.

At first discrimination against school children was an ad hoc and local initiative. But as the Nazis took increasing control over schooling, they introduced formal bans. In November 1938, after Kristallnacht, the Nazi regime completely banned all Jewish children from attending German public schools. In March 1941, the Nazi regime formally excluded Black and Romani children from public schools.

Forced Sterilization of Black People in Nazi Germany

The Nazis used forced sterilization to persecute Black people in Germany, especially the multiracial children in the Rhineland.

Sterilization is a procedure that makes a person unable to father or bear children. Today, enforced sterilization can be prosecuted as a war crime or a crime against humanity under international law. The Nazis forcibly sterilized hundreds of thousands of people, including people with disabilities, Roma, and Black people. Nazi leaders believed that these people represented threats to the health, strength, and purity of the Aryan race.

The Nazi regime forcibly sterilized hundreds of Black people because the Nazis sought to prevent what they saw as “race-mixing.” Thus, in addition to passing the Nuremberg Laws in order to prevent interracial marriages, the Nazi regime used forced sterilization to prevent future generations of Black people in Germany.

Some Black people in Nazi Germany were sterilized by court order, under the 1933 “Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases” (“Hereditary Health Law”). This law mandated the forced sterilization of individuals with certain physical and mental disabilities, including people who fell into the ill-defined category of “minderwertig” or “feeble-minded.” A small number of Black people were among the approximately 400,000 Germans sterilized under this law. For example, Ferdinand Allen, who had a Black British father and a white German mother, suffered from and was institutionalized for epilepsy, one of the conditions listed in the law. He was sterilized by court order in 1935. On May 15, 1941, the Nazis murdered Allen at Bernburg as part of the T4 program (the Nazi program of mass murder targeting people with disabilities).

The Nazis also sterilized some Black people in Germany solely because of their race. In the 1930s, a secret Gestapo program coordinated the forced sterilization of the multiracial children in the Rhineland. As part of these efforts, doctors forcibly sterilized at least 385 children and teenagers by the end of 1937. Because there was no legal basis for their sterilization, their families were pressured to consent to the procedure. During World War II, the Nazi regime forcibly sterilized other Black people in Germany, often without any legal basis. These sterilizations particularly targeted Black and multiracial teenagers born in Germany who were coming of age and whom the Nazis believed were either entering puberty or were already sexually active.

Adapting to Life under the Nazis: Performing as a Source of Income

Most of the Black people living in Germany in 1933 when the Nazis came to power were effectively trapped there throughout the Nazi period. While some tried to leave Nazi Germany, for the vast majority this was not possible. Most Black people in Germany could not receive visas to other countries or legally immigrate elsewhere because of citizenship issues. Black people in Germany had little choice but to adapt to life under the Nazis.

But the economic and social restrictions imposed on Black people made everyday life very difficult and unstable. It became almost impossible to earn a living and provide for their families. Working as performers and in the entertainment industry was one of the only options for many in the community. But even this was an unstable source of income under the Nazis. The Nazification of German cultural life greatly limited the options for Black men and women trying to earn a living as performers.

In response to declining employment opportunities, the Togolese man Kwassi Bruce co-created the German Africa Show in 1934. The German Africa Show was a touring show that was part ethnography and part entertainment. It provided a number of Black performers with an income. The Nazis used the show to promote the cause of regaining Germany's African colonies, which the country had lost at the end of World War I. The Nazi regime shut down the show in 1940.

In 1941, the Nazi regime introduced a formal ban on Black performers appearing in public. A notable exception to the ban was made for the film industry. Black men, women, and children were allowed to appear in propaganda films which served the purpose of promoting the Nazi worldview. Black people (including Black prisoners of war) notably appeared in the film Carl Peters (1941), a biopic of a German colonial administrator who advocated for colonialism and justified his brutality.

Wartime Imprisonment of Black People in Concentration Camps and Other Sites

During World War II, Nazi policies against Black people became more extreme. This occurred in the context of the broader radicalization of Nazi policies against supposed racial and political enemies. Because of laws and policies that sharpened discrimination and racism in Germany, many Black people ended up imprisoned in workhouses, prisons, hospitals, psychiatric facilities, and concentration camps.

There are multiple documented experiences of Black people imprisoned in concentration camps. These include Mahjub bin Adam Mohamed (Bayume Mohamed Husen) who was imprisoned and murdered in Sachsenhausen, Gert Schramm imprisoned in Buchenwald, Martha Ndumbe imprisoned and murdered in Ravensbrück, and Erika Ngando imprisoned in Ravensbrück. Some of them, including Husen and Ndumbe, died in the camps. Others survived and left memoirs and testimonies of their experience. In the past several years, a number of memorial plaques called Stolpersteine (literally, “stumbling stones”) dedicated to Black victims of Nazi persecution and murder have been laid in Germany.

Scholars continue to research and uncover the stories of Black victims of Nazi persecution. Their stories help illuminate not only the experience of Black people under the Nazis, but also the far-reaching impact and tragic consequences of Nazi ideology for individuals and entire communities.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

From 1884/5 to 1918, Germany controlled four colonies in Africa: Togo (today Togo and parts of Ghana); Cameroon (Cameroon and parts of Gabon, the Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Chad, and Nigeria); German South West Africa (Namibia); and German East Africa (Tanzania, Burundi, parts of Mozambique, and, for a short time, Zanzibar).

-

Footnote reference2.

Human zoos were exploitative exhibits in which non-Europeans were put on display and expected to demonstrate their traditions and customs to white audiences. Far from showing what life was like in Germany’s African colonies and other supposedly “exotic” places, human zoos instead presented a distorted, inaccurate, prejudiced, racist, and falsified depiction of Africans and others. Nonetheless, human zoos were big businesses that profited from exploiting people and stereotypes. They were a popular form of entertainment in nineteenth and early twentieth century Europe.

-

Footnote reference3.

Before World War I, Africans from German colonies were considered colonial subjects, not citizens. After World War I (1914–1918), when Germany lost its colonies in the postwar peace settlement, these former colonial subjects effectively became stateless.

-

Footnote reference4.

When a child was born to an unmarried woman, German citizenship law dictated that children inherited citizenship status from their mothers. This was the case for most, if not all, of the multiracial children in the Rhineland.

-

Footnote reference5.

Hans J. Massaquoi, Destined to Witness: Growing up Black in Nazi Germany (New York: W. Morrow, 1999), 1-2.

Critical Thinking Questions

How was the treatment of Black people in Germany similar to the campaign against the Jews, and how was it different?

Investigate the history of Black people serving in the military of your country. When were they allowed to enlist? What obstacles did they face?