Polish Jewish Refugees in the Shanghai Ghetto, 1941–1945

Background

The outbreak of war in Poland in September 1939 trapped nearly three and a half million Jews in German- and Soviet-occupied territories.

In late 1940 and early 1941, just months before the Germans began to systematically kill Jews in large numbers, one group of about 2,100 Polish Jews found a safe haven. Few of these refugees could have reached safety without the tireless efforts of many individuals. Several Jewish organizations and Jewish communities along the way provided funds and other help.

The most critical assistance came from unexpected sources: representatives of the Dutch government-in-exile and of Nazi Germany's Axis ally, Japan. Their humanitarian activity in 1940 was the pivotal act of rescue for hundreds of Polish Jewish refugees temporarily residing in Lithuania.

Destination: Shanghai

The Polish Jewish refugees from Lithuania had heard in Japan that the Free Port of Shanghai was a crowded, unsanitary, and crime-ridden city. Still, they were shocked by the sights and smells that greeted them when they disembarked. In the city's International Settlement, hundreds of thousands of destitute Chinese lived amid a foreign community dominated by a wealthy elite of British and American traders and financiers.

The refugees also found an established community of some 4,000 Russian Jews to assist them, and more than 17,000 struggling German and Austrian Jewish refugees who had fled Nazi persecution in 1938 and 1939. Most of Shanghai's German and Austrian Jewish refugees lived in crowded, dilapidated housing. The most economically vulnerable of them lived in barracks funded by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Still, these earlier arrivals were managing to survive and even thrive. Some had opened small shops and cottage industries. Others had set themselves up as builders and landlords, transforming whole segments of Hongkew, an industrial area of the International Settlement that had been heavily damaged during Sino-Japanese fighting in 1932 and 1937.

Refugees in Shanghai after the Attack on Pearl Harbor

Trapped in Shanghai after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the war in December 1941, Jewish refugees suffered from shortages of food, clothing, and medicine while enduring unemployment and isolation. They knew nothing about the fate of their families. The war disrupted the flow of funds to Shanghai. The number of underfed refugees grew after Pearl Harbor. Refugees were also subjected to Japanese decrees.

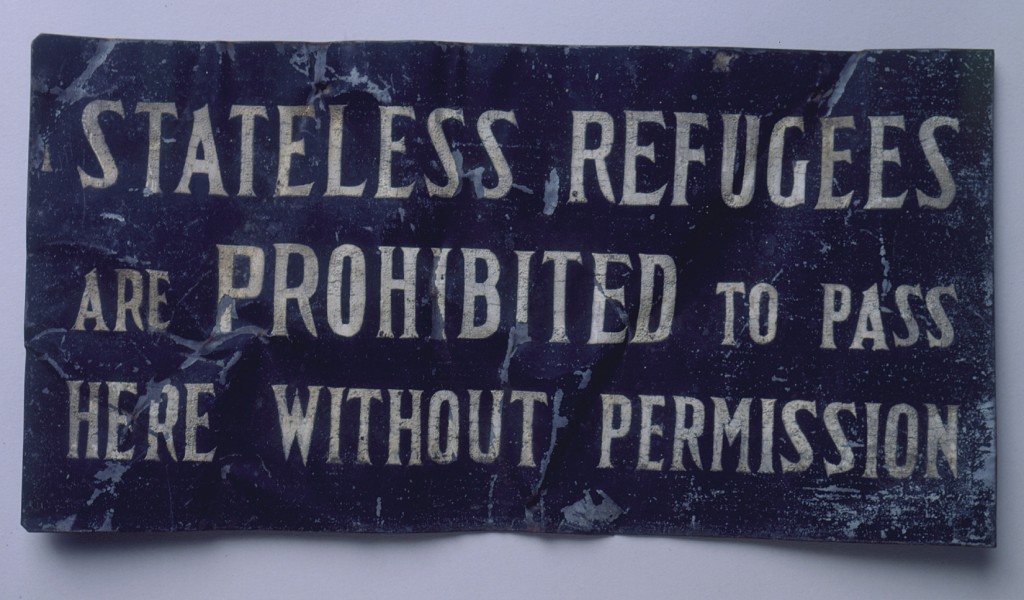

After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese authorities in Shanghai imposed stricter security measures. Accepting that their Nazi ally had left German and Austrian Jews "stateless" by stripping them of their national citizenship, in early 1943 the Japanese ordered these stateless refugees—including Jews from Poland—to live within a "designated area" of the International Settlement. Many refugees in the designated area lived in small apartments off alleyways. They often lacked modern toilets, and every morning buckets of "night soil" were emptied and carted away by Chinese workers.

The Bureau of Stateless Refugee Affairs, headed by former Japanese naval officer Tsutomu Kobota, oversaw the designated area but had little direct contact with the refugees, who hated and feared his subordinates Okura and Ghoya. Limited movement and wartime deprivations made life difficult in the "Shanghai ghetto," as residents called it, though they did not suffer the daily terrors endured by ghettoized Jews in Europe. The Japanese treatment of Jews in Shanghai was comparatively benign.

Polish Jewish writers used a Yiddish expression to describe Shanghai: "shond khay," "a shame of a life." Still, life went on in this foreign and isolated setting. The reading of Yiddish poems, publication of Yiddish and Polish newspapers, and the creation of artwork and plays, though sporadic due to logistical problems and Japanese censorship, helped sustain the refugees transplanted from Poland.

The Japanese forbade overt political expression, but Zionists and Bundists remained clandestinely active throughout the war. Refugee yeshiva (religious academy) students spent the war years continuing their studies. They used books reprinted from those few they had carried with them to Shanghai from Poland or had received from supporters abroad, notably Rabbi Kalmanovich in New York. Students and rabbis from the yeshiva in Mir gathered in the Beth Aharon Synagogue, which had been built by one of the wealthiest members of Shanghai's Sephardic Jewish community. Through the twists of fate and the choices made by their leaders that led them from Poland to Japan and Shanghai, the Mir Yeshiva emerged as the only eastern European yeshiva to survive the Holocaust intact.

Shortly before the end of the war, a US air raid on industrial Hongkew killed 40 Jewish refugees, including seven Polish Jews, and hundreds of Chinese. The entry of US troops into Shanghai was met with jubilation that was quickly tempered by news of the Holocaust. Most refugees had heard nothing since the spring of 1941 from relatives left behind in occupied Poland. It would take them many more months to learn the fate of individual family members and friends.